Why The Verge Is Running a Sci-Fi Series Full of Happy Endings

The tech website's editor-in-chief opens up about why now feels right for it.

Better Worlds is a project about being optimistic about our future,” Nilay Patel, editor-in-chief of The Verge, tells me about the sci-fi series launched by the website that covers technology and culture, and up to this point, has only previously dabbled in fiction efforts. The new series is, somewhat thankfully, fundamentally opposite to Black Mirror.

The result, Better Worlds, is an 11-part series by an impressive roster of authors with diverse outlooks and backgrounds, and one unifying perspective: optimism. It debuted January 14, and new stories will run every Monday and Wednesday through February 13. The cultural turmoil of 2017 and 2018 made the staff at the website best known for tech news realize it was time to launch something more optimistic, and all but one story in the series will be paired with a video or audio presentation.

So far, four stories have published, with “Monsters Come Howling in Their Season,” by Cadwell Turnbull, going live on Wednesday morning. Monday saw the anticipated release of a short story by John Scalzi (“A Model Dog”), which is perfectly matched with an animated video by Joel Plosz.

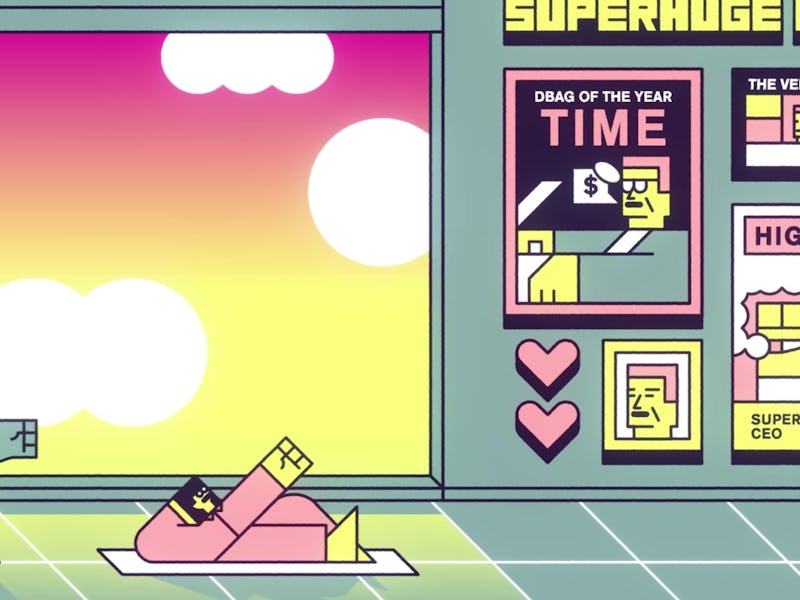

“A Model Dog,” the series stand-out thus far, tells the story of two engineers who are tasked with making a robo dog for their boss, the CEO of a Google/Facebook-like company with more than a few clues he was modeled after SpaceX/Tesla CEO Elon Musk. The short story and accompanying video (Better Worlds is edited by Laura Hudson, previously culture editor at The Verge) combines a heavy dose of smart-ass humor, blocky, playful animation, and ‘80s-inspired inspirational jams. It would be easy to watch a fully developed series on the lives of these two people, and the three-minute video feels more like a pilot than a short film. Like all stories in the series, “A Model Dog” has a hopeful ending that’s slightly emotional. (Pro-tip: Be sure to read each short story and then watch the video or listen to the audio play. The axiom about books enriching the movie still applies.)

“I’m really hoping this series inspires people to not only not take everything for granted, but to work hard on building the positive futures that we actually need,” Patel says.

I recently spoke with Patel about the series. The following is our conversation, lightly edited for clarity.

Inverse: It’s quite a lineup of authors that you’ve chosen.

Nilay Patel: The first thing is that Better Worlds is a project about being optimistic about our future. That was our first extremely wide net. Who are the people who are thinking this way, who are dreaming this way? Then you look at the selection process. If you look at the lineup we have, we also placed a pretty big emphasis on making sure we have a really diverse set of viewpoints. [We wanted to] make sure that the people imagining this future for us represent an incredible array of backgrounds and of outlooks.

I think for so long in these spaces, the future has been written by one set of people, and we’re inspired by those people all of the time, but we wanted to make sure that The Verge is participating and providing a vision for the future. We were building on a foundation of diversity and optimism. Who are the people who are thinking really big, and then how can we make sure that we’re placing an emphasis on this huge diverse array of voices?

The two big organizing principles were definitely: What are we seeing that’s optimistic, what are we seeing that’s big? And then, what are we seeing that’s new from really fresh voices?

Is a strong moral compass required to be part of this series?

We take too many things for granted. We live in a world that is the science fiction future of the past, right? I mean, I stood in line to take public transit to work today and every single person was holding a broadband communicator that connected them to all of the information in the world. That is a powerful reality that was actually science fiction not so long ago, and we take it for granted. We really truly take those things for granted; the enormous complexity of the world that we live in and the enormous amount of effort it takes to build that world, to conceive that world, to engineer that world.

Our stories, they look at if we use all this stuff for good — instead of the dominant theme [that] the world has gotten away from us, or that we can’t control the algorithm. Or, ‘Hey, the state will oppress us until all of us live forever,’ which are all very normal themes. If you look at our stories, you see that some of them are set in those worlds. “A Theory of Flight” by Justina Ireland is; we led with it because it was one of our very favorites. I think the animation work is incredible as well. Here’s an engineer, and she comes back to her community, and she does good work through engineering and effort in that community. The theme here is effort. What do we do with the work? I think we’re missing that a lot lately.

Can you talk about your thinking about making a story like “A Theory of Flight” a video, and then “Online Reunion” an audio story?”

Better Worlds as a project is probably the most collaborative big group creative thing that The Verge team has done in a while, if not ever. “A Theory of Flight” felt very visual; it felt very big. When I spoke to our art director, Will Joel, we were literally imagining the scenes of the animation before we ever went out. So he went out and talked to a bunch of animation companies. The thing about Better Worlds is that everyone wants to be a part of something with this.

[Laura Hudson], our editor, took some of the stories and wrote scripts for them that we then brought to the animation studios. The animation studios interpreted them. We’re basically making little movies here, so there were some questions of, “Hey, the main character in ‘A Theory of Flight,’ how does she walk? What does she look like? What does she sound like?” It was fun to have that conversation going between the animation company, our art director Will, Laura, and the authors.

Launching a fiction series has sort of been every magazine’s wish that rarely comes true. When did it become a goal of yours? I know obviously [sponsorship from the Boeing Company] makes things not only possible, but probable, but how long has this been a wish of yours for The Verge?

A long, long time, a long time, since we started. We’ve actually run some fiction in the past on The Verge. We did some short stories on the weekend. It’s just fun to get out of the malaise of the news sometimes. Last year in particular was just a hard year, and so in the middle of it, we started thinking, one thing we know The Verge provides for people is respite. People come to The Verge, we do a lot of policy news. We cover really hardcore privacy news. We cover everything that’s been on Facebook, we cover net neutrality. We’re in it.

But we also know that they come to us because they want a break and they want to just look at fun new phones. They want to imagine what the living room of the future is gonna look like when they buy a cool new TV.

What I’ll tell you is that it’s great that it’s sponsored. I’m very pleased that we got a sponsor for it, but we were gonna do it regardless of that, actually. I think there’s a remarkable market demand both from our audience and then, obviously, I have nothing to do with the sales side, but the commercial side of our business was able to go out and find demand for this thing as well.

Reading “A Theory of Flight” and watching the video, I have to admit I still love reading more than anything — there were so many moments I’d love to see in the video, scenes that weren’t there. One line is about how the people building a rocket with open-source plans want to load up all the folks in the neighborhood “who feel like striking out for paradise.” It feels tangible to me, like when a neighborhood goes in on a lottery ticket together. What impact do you hope that this sci-fi series about hope makes? In a world where there’s 50 stories a day on The Verge, how does this stand out?

We only tell stories about that complexity gone wrong, and that’s the new cycle that we live in, and The Verge has a big obligation to that, and we’re gonna keep doing it. But I really want us to inspire. The Verge reader I think about the most is the 14-year-old kid in Wisconsin, who was me. I was a 14-year-old kid in Wisconsin, and I read science fiction, and I read tech magazines, and I literally dreamed about building a future. I think about that group for us more than anything; like we should be literally showing them a future they can participate in, and they can build and important that they can be a part of.

Even the dystopian has to be informed by positive thinking. Laura, when she was pitching the story, kept saying, “If you eliminate the space for this kind of thinking, it will just go away. It won’t be there.” This is very basic for many readers, but I’ll put it out there: Think about the [Asimov’s “Three Laws of Robotics”]. The world thinks about the three laws of robotics all the time. Those were invented. They were fiction, and now it comes up in every meeting with a robotics company that I can think of.

"I just think that we have to create this vision of what it looks like when it goes right."

I just think that we have to create this vision of what it looks like when it goes right, or what it looks like when the tools are used for good, or what it looks like for the tools to be wielded by optimists and not just pessimists or ad tracking companies or whatever Mark Zuckerberg is doing.

Some of these stories are built in worlds that kind of look like dystopia, but what is happening is the science and the engineering is being used to improve those spaces. The goal of [Better Worlds] is a bunch of people are gonna read these stories and remember that complexity can be used for good and historically, the arc of it has been used for good. Hopefully, a bunch of kids who are dreaming of being engineers or authors or whatever realize that there’s another side of the equation and what is so dominant in our culture right now.

That’s great. This has been quite the uplifting interview. Will there be a Better Worlds Season 2?

I certainly hope so. We’re two episodes in. We got two stories out, one video, and one podcast. Everything seems to be going well. The reaction is good. We’ve got a ways to go, but it feels great. The John Scalzi story that’s coming on Monday and that video is just my favorite. It’s funny. I mean it’s wild. The great thing about a program of this length and this scope and this ambition is usually we launch a thing and a week later we’ve moved on. We’ve got this until mid-February, so we get these little jolts of optimism coming at us a couple times a week for a month or so. I’m excited about that, and if it goes the way I think it’s gonna go, will definitely be a Season 2.

Some of these stories seem really plausible (A.I. that can help an island manage hurricanes) and others not so much (a lever that resets the world). Did you consider striking a balance between the two — plausibility versus not? For example, The Science of Interstellar gives you a sense it’s possible; the film does not accomplish that. So how do you strike a balance with Better Worlds ?

I think I’m much more on the hard sci-fi line of things — “tell me where the screws went in the spaceship” — but I recognize that we have a huge audience. Most of the things that we are surrounded with today, if we had written them in a sci-fi story 20 years ago, people would’ve had this conversation about the implausibility, right? Maybe there won’t be a lever that resets the world, but if 20 years ago you had been like, “Netflix is gonna put out Bandersnatch, and Netflix itself will be a character in Bandersnatch, and it will explain itself to a character in the ‘80s that it’s being controlled by a human character in a video,” that’s nonsense. I think it’s important for us to set the goalpost really far. There’s that balance: We have some stuff that is, what if today but more, and then we have some stuff that is, what if it’s the farthest out that anyone can possibly imagine.

Your career in technology journalism goes back awhile. The negatives about our industry are well-documented — journalists too cozy with companies, content farming, hot takes — what do you see as being the positive changes you’ve seen in technology journalism since starting? Is it projects like this?

In order to bankrupt all my competitors, I will say that large, complicated fiction packages are it.

But this is something that we are fortunate to do because of the size of the platform that we’ve built. We’re lucky that our sales team was able to go out, and it’s wonderful that Boeing wanted to participate as a sponsor. We would’ve done it without the sponsor.

In order to stay sort of fresh in the minds of readers who are swiping through a zillion stories on Apple News, do you see fiction packages and projects that might’ve seemed crazy a few years ago [as the next step beyond the news cycle?]

There’s more better and more important and more vital tech journalism in this world today than there ever has been before, and so I am very proud of The Verge that we started out to take it seriously and do it big, seven years ago, six years ago. If you look around now, The New York Times is doing some of the best Facebook journalism that exists. The whole world is interested in what Facebook and Google are doing. There is a tremendous amount of journalism being done around data privacy. There’s a tremendous amount of emerging behavior journalism done around teens and social platforms.

The YouTube community is building an entirely new kind of journalism, an entirely new kind of audience around tech that I think about every day. It’s inspiring. That’s why we do what we do. The mission of The Verge is that new technology creates democratic platforms for people to participate, that creates a new kind of culture, that creates a new set of needs, that creates a new kind of technology. That’s the cycle that The Verge is built around.

Sure, we’re faced by a ton of competitors; some of them make us better, some of them frustrate the hell out of me because they’re way better than us, and we have to get even better. Some of them are just doing it.

It’s a much broader set than it ever was before, but I think that’s a net good for the world. For us, it’s the thing that we’re the best at is doing that tech journalism for the people that come to us because they love new phones, they love new ideas, they love new cameras, they love laptops, they love SpaceX, they love Tesla.

They come to us because they’re so inspired by science and technology that we’re telling the story. Because we have that credibility, we’re in it with you, we’re passionate with you, we can say, “Hey, Apple and Google fucked up today.” “Hey, Facebook is doing a bunch of sketchy shit.” Because we’re part of the community, we’re able to say, “Hey, we have the credibility to say when things are going horribly wrong, and you should stop it.”

We have the credibility; we just ran a huge package on what is honestly a dystopian reality for the Amazon Marketplace sellers. Everything we do has to rebound to our core credibility, and that credibility does not always have to be based on tearing things down. Often, it is based on sharing the enthusiasm of our audience.

Have you thought about breaking Better Worlds out to its own Netflix series or something like that?

I sure have. One thing at a time. We’re gonna publish our 11 stories in five videos and five podcasts. We’re gonna see where the audience takes us, and if Netflix wants to come calling, there’s somebody here to take their call.

What did you grow up reading and watching?

I’m all over the place. I am [38], so I grew up in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. I literally, I went to a school library that was full of worn out Bradbury paperbacks. I read a ton of Asimov, and then I think I made the shift to watching, well I think the entire culture made, to mostly consuming sci-fi in movies as I got older. My roots are very much in, “What does a computer look like? What does it mean if we go to a new place and build a new kind of society?”

Which author was new to you in this series and what did you take away from their work?

I really liked “A Sun Will Always Sing” by Karin Lowachee. It’s such an enigmatic story. I had to read it twice to really feel it, and then kind of on the next read, and the next read, it started to hit me more what was happening, so I appreciated the enigmatic beauty of that particular story.

Do you hope that Elon Musk reads this series given his affinity for sci-fi? What do you hope he takes away from its themes of hope and searching for a better life given his work with Tesla and SpaceX?

That’s why he builds the things he builds, or at least that’s why he says he builds the things he builds. Maybe he should spend more time reading sci-fi and less time tweeting.