Battlestar Galactica’s Divisive Sci-Fi Prequel Is Still Deeply Weird

So say... some of us.

One of the most interesting things about the 2003-2009 reboot of Battlestar Galactica was how quickly into went from being a risky show that old-school fans mistrusted, to being one of the most popular word-of-mouth shows ever. Immortalized in the Portlandia sketch “Battlestar Galactica,” it seemed like, at some point, the whole world caught up on Battlestar via a binge, which meant, by 2009, when the finale aired, the show was a genuine crossover hit. This is impressive considering that streaming TV was still emerging and that the series aired on the SyFy Channel, which, just a decade later, would be a kind of purgatory that briefly murdered viewership for The Expanse.

But just like its ragtag, fugitive fleet, BSG was an underdog show that achieved a scrappy victory. And because it set the standard for what big sci-fi TV could be like in the 21st century, a follow-up BSG spinoff was almost assuredly going to be great, too. Right? Well, not exactly. While noble in its originality and uniqueness, the BSG prequel, Caprica, is still a strange beast, 15 years after its premiere on January 22, 2020. Here’s why the show is cool, but why it also kind of betrayed the mystique of Battlestar.

Set 50 years before the start of the regular series, and well before both versions of the Cylon Wars, Caprica was determined to tell a science fiction story that was even more grounded than BGS. Yes, the action was taking place on the fictional (distantly in the past) planet Caprica, but the production design of the series was consciously designed to look as Earth-ish as possible. While BSG justified its analog, dieselpunk aesthetic with various in-world explanations, Caprica’s aesthetic landed somewhere between Sex and the City and Mad Men. Because the “Twelve Colonies of Man” were decimated in the debut of Battlestar, we didn’t have to think too hard about the not-quite-Earth culture all that much. But, by setting an entire show on Caprica, the BSG world-building paradoxically became slightly less credible by showing us more.

In theory, Caprica is a science fiction family drama, specifically on the Graystone family. The dad is Daniel Graystone (Eric Stolz) and he’s a computer engineer. His wife, Amanda Graystone (Paula Malcomson) is coded like a New England snob, and their daughter, Zoe (Alessandra Torresani) is a rebellious teenager, who is dead-set on finding... God.

This is where Caprica got weird, and got weird fast. In Battlestar, we were meant to understand that regular humans had a vague, polytheistic religion, worshipping several gods, that sometimes aligned with Greek myths. But, we also learned that the Cylons believed in “the One True God,” which meant the evil AI in BSG were waging a holy quest against humanity, who, oddly, they did not view as their creators. What Caprica did was, in a very roundabout way, explain why the Cylons believed in One God, and how that religious conflict motivated everything.

The cast of Caprica: Paula Malcomson, Eric Stoltz, Alessandra Torresani, Magda Apanowicz, and Esai Morales.

More specifically, Caprica’s goal was to show the origin of the Cylons wasn’t exactly what you thought it was. Whereas the backstory (and opening credits) of BGS told us that the Cylons were created by Man, but then they evolved and rebelled, Caprica showed up and said, well, it was a bit more complicated.

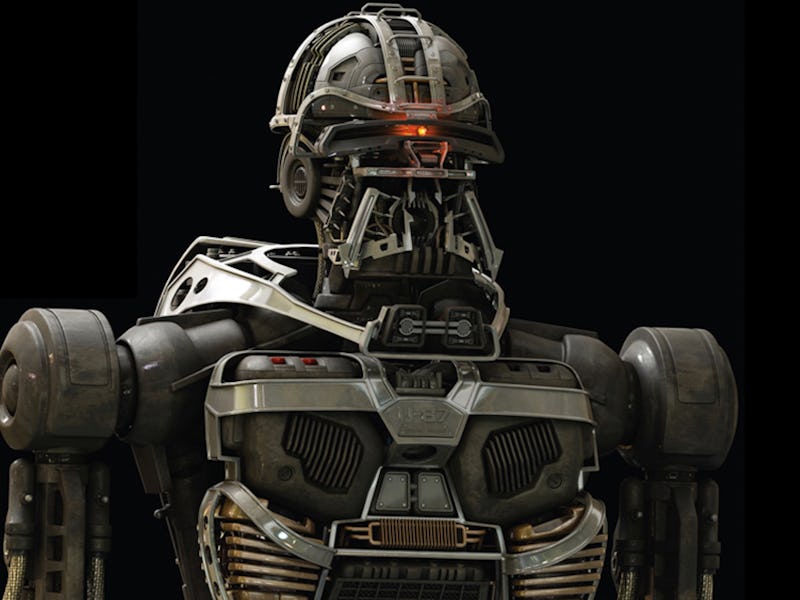

In short, Caprica’s biggest revelation was that one of the earliest Cylons —one that physically looked like the classic Cylons from the 1978 series — was actually inhabited by the digital consciousness of Zoe Graystone. Physically, Zoe is slain in a religiously-motivated terrorist bombing in the very first episode, meaning Torresani mostly appears throughout the series as a kind of AI ghost.

Putting Zoe’s spirit into the U-87 Cylon has a lot of complex implications throughout Caprica as a series, but relative to the larger BSG mythos, this choice simplified the mystery of the Cylon origins and their later obsession with a monotheistic religion. In short, the reason why Number Six and other Cylons believed in a “One True God” was because one of the progenitors of the Cylon race was augmented by the ghost of a human girl who happened to have been in an extremist religious cult. This may sound like an unfair simplification of Caprica’s themes, but the series was even kind of marketed this way: Torresani famously appeared on promotional posters holding an apple, making it clear that this was some kind of sci-fi Garden of Eden story.

While the cast (and Torresani in particular) are excellent in the show, the real issue with Caprica is that outside of its dot-connecting to BSG it failed to give us a cast of characters that we actually cared about. Sure, there’s a prequel trap here because all these people are doomed. But that wasn’t what made Caprica so odd.

Will the real Zoe please stand up?

Instead, it made the mysteries of Battlestar a little less mysterious and slightly messier. Characters in BSG gradually became corrupt, or eventually came to see the error of their ways. In Caprica, it seems characters are all amoral as hell and ready to betray and backstab so often that sometimes you can’t keep track of who is betraying and backstabbing who. In fairness, this was a problem BSG had too. The show was generally better in Season 1 and Season 2 when all the mysteries were firmly in the background, and the backstabbing was somewhat predictable. By the time we started to learn which humans were secretly Cylons, and everyone was shouting at everyone all the time, the series, arguably, got less and less interesting. Caprica was seemingly determined to give us all the answers from the start, which, in a sense, led to its downfall.

Like Adam and Eve eating that apple of knowledge way back when, Caprica’s temptation to explain the wild world of Battlestar Galactica in a kooky prequel was, in retrospect, totally understandable. But because that knowledge came with pitfalls and reductive simplifications, this origin story was doomed to fail. The Cylons were scarier, sexier, and more compelling when we didn’t know why they evolved. Once we were given that answer, the universe of Battlestar seemed much, much smaller.