From his disregard for people’s feelings to his literal axe-wielding, there’s a lot of evidence that Patrick Bateman is truly an American Psycho. But one of the clearest indicators of his truly sinister personality? His downright creepy smile. No genuine, non-murderous person looks this pained by human interaction.

So what does a perfect smile actually look like? According to a study published Wednesday in the journal PLOS One, it comes down to one simple rule: less really is more.

Lies.

To identify the components of a perfect smile, Sofia Lyford-Pike, a reconstructive surgeon at the University of Minnesota, and her colleagues created a 3D animation of dozens of different smiles. Then, they plopped 802 participants down in front of a computer and asked them to rate the smiles according to the effectiveness of the smile and its genuineness and pleasantness. The researchers also asked participants about the perceived emotional intent of the smile — in other words, was this person truly smiling at you to indicate their openness, or were they trying to get something out of you, American Psycho style.

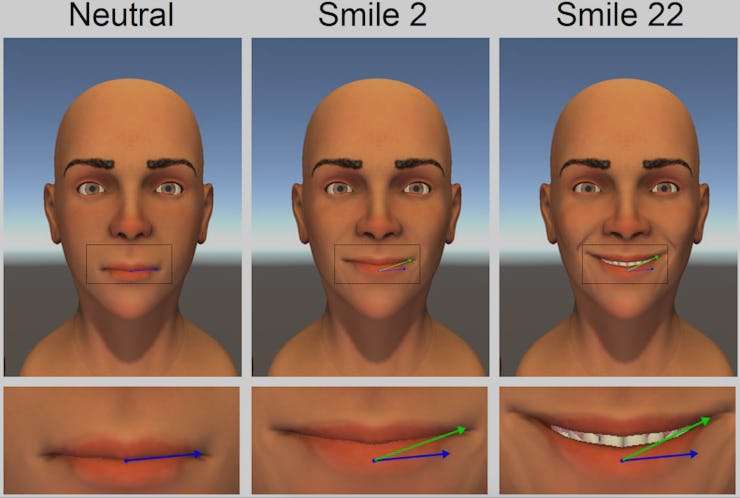

These diagrams show the angle of different smiles.

The best smiles had two essential things in common. First, smiles that developed slightly asymmetrically — say, your lips teased up on the left a few milliseconds before they perked up on the right — seem to be the best loved. Second, the study revealed that bigger smiles aren’t always better. Instead, participants reacted positively to smiles that had a balance of visible teeth, the extent of the smile, and the angle.

If any of these were off — if the left corner of your mouth lagged way behind the right side, or if your smile was closed tight but you had a lot of teeth showing — the participants rating the smiles felt a little uneasy. “We observed somewhat of a Goldilocks Phenomenon, such that successful smiles needed just the right amount of teeth for the given smile angle and extent,” Lyford-Pike says. “Too little or too much can produce smiles that are perceived as fake and creepy[.]”

This image shows the delay in smile symmetry. Delays between 25 and 100 milliseconds were most appreciated. Delays longer than that threw the smile judges off.

Not unsurprisingly, the researchers didn’t set out to study this question in order to help the Patrick Batemans of the world better assimilate. Rather, Lyford-Pike and her colleagues want to use this research to help patients who suffer from smile-altering issues like stroke and Bell’s palsy.

Typically, medical experts try to help patients learn to smile big and bright, using a mix of physical therapy exercises and other interventions. But, Lyford-Pike says, the new research will allow doctors to target, with scientific precision, the parts of a smile patients really need to focus on rehabilitating.

This is important because smiles are prime social currency. We use them to communicate a lot of our emotions and goodwill towards other. The researchers hope their study will help those struggling with facial paralysis and other issues get back to life as usual faster and with more confidence.

That’s not the only potential implication of the research, Lyford-Pike says; she hopes the research can be used to build more human-like animations and robots.