Nice People Survived Evolution Because of Sexual Selection

Morality goes a long way in the survival of the fittest.

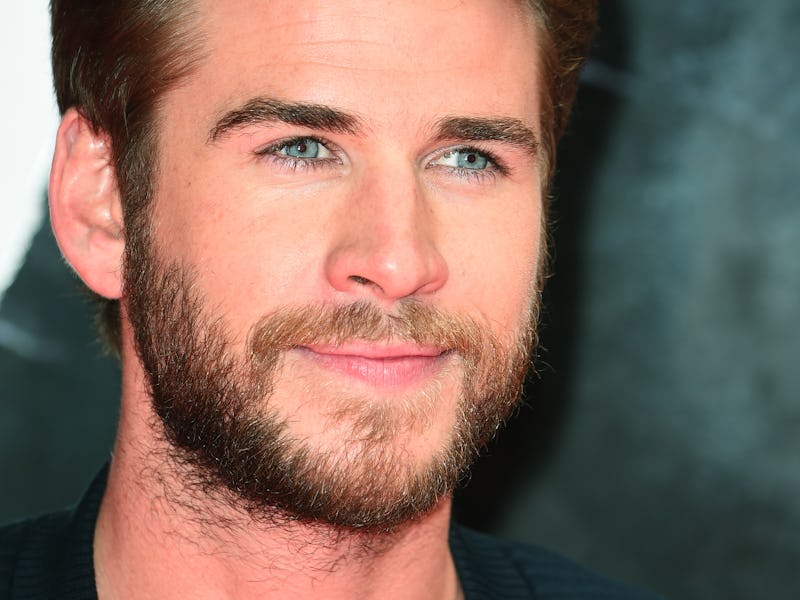

Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection suggests that humans will always go for the visibly fittest mates. In the case of The Hunger Games, that’s clearly Gale, played by the comically handsome Liam Hemsworth. But Gale, like so many individuals among history’s physical elite, didn’t get the girl. Evolution is actually a lot more complicated than that. While Homo sapiens are the product of natural selection, a different type of selection — the sexual kind — explains why sweet, noble Peeta won out in the end.

While natural selection refers to the way individuals better adapted to their environments tend to survive and pass on their genes, sexual selection is a “special case” of natural selection in which mating preference drives evolution — even to the point where a species develops traits that actually decrease its chances of survival. Geoffrey Miller, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at the University of New Mexico and a leading researcher in the study of this theory, believes sexual selection drove the evolution of moral virtue — thus producing the Peetas of the world.

“In my experience… it seemed like a lot of people fell in love with these moral virtues,” Miller tells Inverse. “And also that they broke up with people who had moral failings, who cheat or lie or give up or have bad political values.”

This may seem to run counter to the adage that “Nice guys finish last” or that “survival of the fittest” is the ultimate law of nature, but Miller argues that being morally reprehensible actually decreases a person’s chances at survival.

Nice guys may actually win the evolutionary long game.

In 2007, Miller published an article in the Quarterly Review of Biology arguing that morality is actually a relatively quick and easy way of advertising one’s fitness to a potential mate. While status and beauty count for something, they’re not everything: Having good morals, he found, had direct benefits on the evolution of ancient humans. People came to prefer partners that shared their food, cared for them when they were sick, and, crucially, were faithful enough that there was no question about the parentage of their kids, making them worth investing in. These good moral qualities persisted, even if the individuals who displayed them weren’t super hot. Miller argues that, over time, as the Peetas of the world continued to thrive and the Gales were forced to become more generous to get a mate, all of humanity slowly changed for the better.

“Any given moral ability or moral virtue that has any kind of payoff… it’s worthwhile for a sexual partner to pay attention to it… because it may be passed on to your kid so they can act morally,” Miller says. “Even if it’s just got survival benefits, we would rapidly evolve mate preferences. I thought of it as supercharging the moral evolution process.” In other words, Miller thinks that having a strong relationship with your mate means that your genes are more likely to be passed down, thus transforming good behavior into a good evolutionary strategy.

Miller’s research has led him to study “virtue signaling,” which is, in a sense, the culmination of generations of sexual selection for do-gooders. Virtue signaling describes how humans intentionally display the things that make them good. To advertise ourselves to potential mates (or even friends and employers) that we’re good people, we might ask for donations to a charity instead of a birthday gift or go vegan. These impulses are excellent ways to tell people we’re good, Miller says, but they sometimes prevent us from being more introspective and honest about what we actually feel and believe.

Some of these misguided virtue signals have been funny. Just try not to chuckle about the absurd maelstrom that was Kony 2012, which led middle schoolers to think their rubber wristbands and Facebook shares would take down a Ugandan warlord. But some virtue signaling may be more serious, like when students protest right-wing speakers on college campuses, which Miller argues is virtue signaling in the extreme. Plus, all of it is amplified in the age of social media, which is one giant signal boost.

Miller hopes this type of inquiry continues, even if it makes us squirm. “People have a fear that if they think too hard about these issues, this will make them sound bad, like a psychopath,” he says. Continuing to analyze why we’re good might help us do a lot better — and, for people like Peeta, serve as a reminder that behaving that way is actually well worth it.