Ancient Teeth Prove We're Not Getting Enough Vitamin D

Hello, sunshine.

Vitamin D (which is actually a hormone, names be damned) helps us build and maintain healthy bones, but research published Thursday in Current Anthropology used teeth to figure out why urbanites are in need of some serious D.

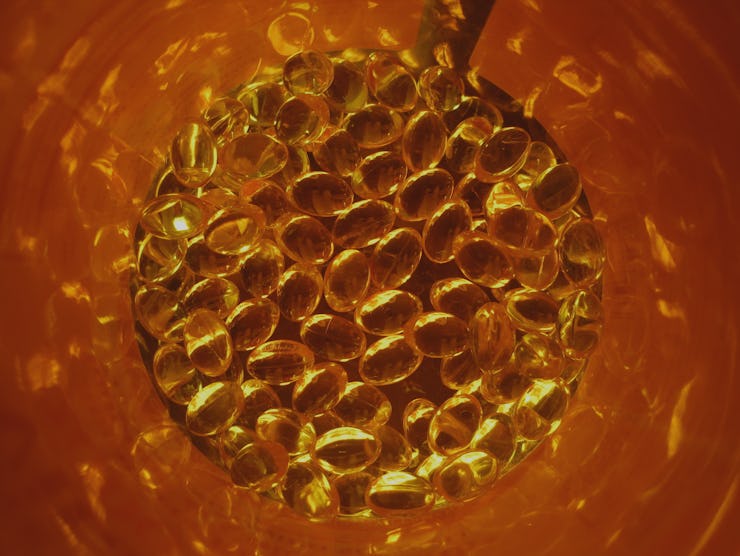

A quick primer: Vitamin D is an essential part of health, primarily coming from UVB rays in sunlight, but you can get it also at the grocery store as supplements and in food like cod liver if you happen to live in the dark Arctic or simply don’t go outside as much as an office peon.

In fact, there’s been a spike in vitamin D deficiency, according to Megan Brickley, a biological anthropologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, and our office-bound culture is partially to blame. Brickley tells Inverse that this is compounded by the fact that when we do go outside, we’re often slathered in sunscreen — good for our skin, but a little sun is typically necessary to ward off vitamin D deficiency.

What happens if you’re lacking in vitamin D? Most people who are mildly deficient don’t have clear symptoms. But those who are severely deficient can develop a devastating disease called rickets, which stunts the development of the legs and hips in childhood and causes a lifetime of pain.

It’s been difficult to analyze this problem across time and say for certain whether the disease has been on the rise. Brickley and her colleagues figured out a surprising solution last year, though: with ancient teeth.

Using interglobular dentin — the calcified tissue that, along with enamel, composes teeth — they effectively measured vitamin D deficiency in people living hundreds and even thousands of years ago. Teeth are kind of like trees, according to the unusually romantic press release, and when someone doesn’t get enough vitamin D, it leaves tiny rings in the teeth that can be detected centuries later.

Using this same method, Brickley analyzed teeth for interglobular dentin. She demonstrated that as people moved out of agricultural communities and into cities, deficiency exploded.

It’s important to note Brickley’s not giving out any prescriptions. Her main goal, she says, is strictly anthropological: to encourage other scientists to use the thousands upon thousands of teeth stashed in museum collections around the world in a new and exciting way.

For the rest of us, the impact of this study on our lives is a matter best discussed with our doctors, as vitamin D has definitely been overhyped before. But it does sound like we could also spend a little more time in the great outdoors. It’s that or cod liver, folks.

Abstract: Vitamin D deficiency is now widely recognized as one of the most common health conditions in the world, with important consequences for overall health. Levels of deficiency appear to be rising, but the extent to which past humans were affected by vitamin D deficiency and the roles of this hormone in past human health are currently unknown. The discovery that mineralization defects in tooth dentin reflect periods of deficiency and are preserved in our earliest ancestors offers a unique opportunity to provide information on past social and cultural organization and, with further work, to contribute to ongoing debates on change in skin pigmentation. Here we show that humans from some of the earliest Middle Eastern and European communities were affected by deficiency, but levels and severity appear to have increased notably through time. On a simple comparative scale, severity of deficiency was four times as high in Greek communities in 1948 CE as in early farming communities from ca. 3000 BCE; some individuals in the later periods would have had rickets. Research using interglobular dentin in humans and nonhuman primates has the potential to fill in many important gaps in understanding past and present aspects of vitamin D deficiency.