3D-Printed Ovaries Let Infertile Mice Give Birth

But don't expect artificial human ovaries anytime soon.

We can already 3D-print bullets, DNA strands, and even a whole house — so it was only a matter of time until mice ovaries were added to the mix.

On Wednesday, researchers announced in Nature Communications that they’d successfully implanted 3D-printed ovaries into mice and — drumroll please — healthy pups were eventually born. While the technology is still a ways from being successfully used in humans, it’s a big breakthrough, especially given all the problems we’ve had with 3D-printed functional biological materials.

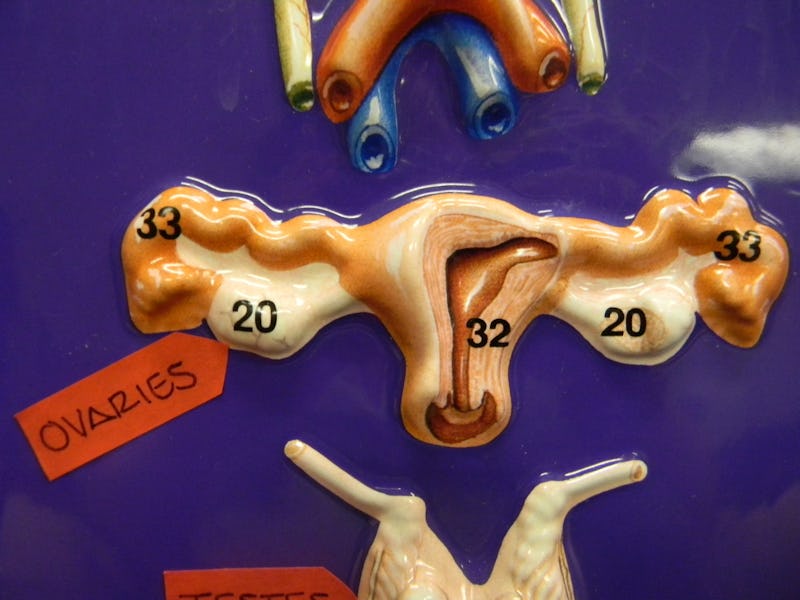

Ovaries are, more or less, the reason we’re all here: They’re the site where human eggs are manufactured and stored until they’re ready to descend into the uterus to be ignored (thanks, birth control!) or turned into a child (if you’re into that). They also help to regulate the hormones coursing through the body.

Ovaries have (so far) proven difficult to replicate in a lab. Past attempts to 3D-print ovaries have failed, because ovarian follicles — which cradle the eggs until they’re full grown — have to be soft and flexible, but also strong enough so they won’t collapse when they’re implanted into the mouse or (one day, scientists hope) a human.

The latest research group seems to have struck the right balance, thanks to the microporous hydrogel they used as their printer ink. A combination of a fully thickened collagen-based gel and a watery solution, the hydrogel created a durable and pliable material.

The researchers also took the geometry of the ovary to the next level. The ovary is basically a scaffold for the soft, complicated network of follicles, so to create an artificial ovary, the researchers had to determine the right structure — a combination of angles and support beams — for their 3D-printed scaffolding. In cultures with only one support beam, the follicles struggled. But with two or three beams, the follicles thrived.

It was this refined multi-beam design, at optimal 60-degree angles, that was ultimately implanted into the test mice and created living, squeaking pups.

Temper your excitement, however: This success doesn’t mean we’ll have human children born from 3D-printed ovaries running around anytime soon. The structure of mice and human ovaries is fundamentally similar, but the size is drastically different. While the new implant worked in mice, researchers still have to figure out the right size, shape, and material for a 3D-printed human ovary.

That doesn’t mean there isn’t an incentive to try. Numerous factors can take a toll on human ovaries, from cancer to genetic mutations. Giving women a chance to have children or restore essential hormonal functions is a major — and noble — research priority.