40 Years Ago, Apple Changed Computers Forever. Can It Happen Again?

The Macintosh is credited with popularizing the graphical user interface for computers. There’s a chance the Vision Pro could do the same for AR headsets.

From mouse inputs to app icons, many of the aspects we take for granted about the computers we use every day were introduced to the world by Apple’s original Macintosh in 1984.

Apple launched the first Mac 40 years ago today to build on the success of the Apple II (primarily designed by a team of engineers led by Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak) and correct the fatal misstep that was the Lisa. Years of software development and hardware modification to devices like the Apple II had revealed the potential of computers as truly personal devices you could create and tinker with, and the Macintosh connected the final dots by making computers accessible to everyone.

The graphical user interface (GUI) that the Macintosh is credited with popularizing is rudimentary today, but if you squint, it’s not nearly as far off from the Windows 11 or macOS Sonoma as you might assume. Navigating an interface with a mouse cursor radically upended what “computing” was at the time, and its hold on how we interact with technology has only deepened as it has become less technical.

Multiple decades after the Mac, Apple is trying to define the edges of what it claims is the next big thing — “spatial computing” — with the Vision Pro. The question is whether there are fixes for the awkwardness of virtual and augmented reality headsets in the same way there were for desktop computing.

The New User Interface

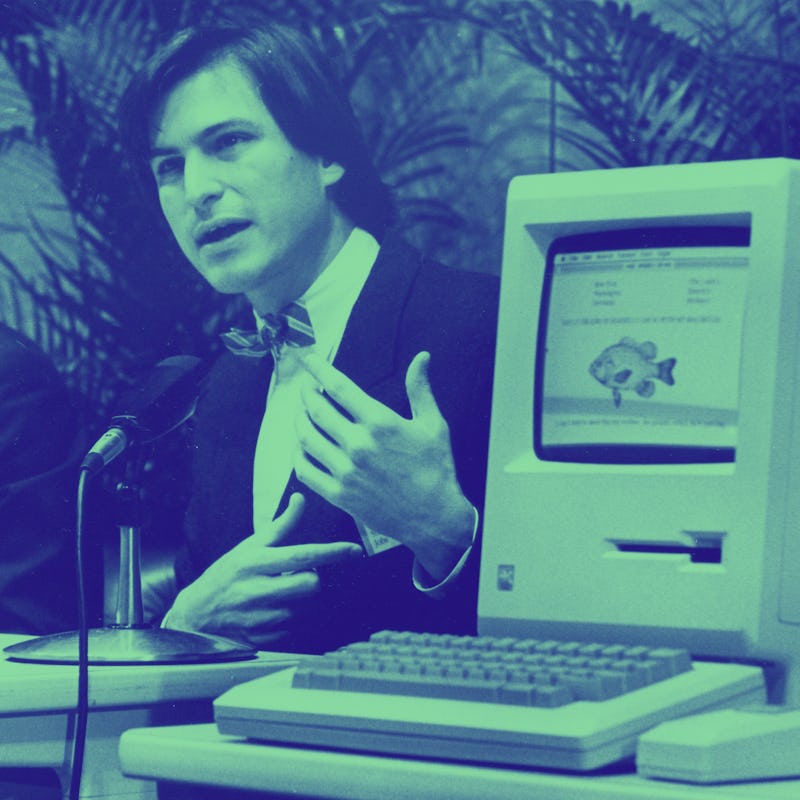

The Mac’s highly visual, mouse-driven operating system was a revelation.

The Macintosh was an all-in-one computer that included a keyboard and mouse, alongside a housing that contained the monitor and motherboard. It looked a bit like an old TV with a floppy disc slot, and didn’t exactly set the world on fire with only 128KB of RAM. The 9-inch monochrome display was also technically smaller than other computers available at the time.

But where the Mac slacked in some of its hardware capabilities, it made up for them with its software. Apple’s $10,000 Lisa was actually the first of its computers to sport a graphical user interface (and Steve Jobs was famously “inspired” by research done by the Palo Alto Research Center, then Xerox PARC). Still, the Macintosh’s System Software was the operating system that most people were introduced to first. It’s strange reading reviews from the time and hearing how alien some of the more normal elements of the interface seemed to new users, but it really was novel.

Here’s how The New York Times described navigating the GUI in its review:

“You find either a word or an icon or pictogram on the screen representing what you want the computer to do, then slide the mouse on your desk to move the cursor into position over that screen object, then press the button on the mouse to activate that particular part of the program.”

Now some of this over-explaining is due to the wide general audience NYT writes for, but still, it’s humorous now to think of the idea of “clicking” needing a paragraph of thorough explanation. Obviously, people took to it quickly, though, because it’s still our dominant input method, even if the mouse has broadly been replaced by a finger.

What visionOS Gets Right

VisionOS keeps interface elements easy to see and select.

With visionOS on the Vision Pro, Apple is trying to make another mouse-level breakthrough. Since the company first introduced visionOS, the new operating system for Vision Pro, in June 2023, it’s seemed disappointingly similar to its past work, especially iPadOS, which it lifts many of its default apps from. Multiple hands-ons later, though, and it seems like the visuals are really only half of the picture, Apple’s big idea is eye tracking.

visionOS is designed to primarily be navigated with your eyes. You look at app icons and pinch your fingers to select them; look at a gesture bar and grab it to reposition and anchor windows in your physical space; look at corners and pinch and drag to resize windows. Generally, everything is driven by what you can see and where you’re looking.

Key to Apple’s whole premise is that you have complete control over when and how much your vision is obstructed, and the outside world always has access to you. EyeSight, the strange outer display that recreates your eyes while you’re wearing the headset, serves the dual purpose of letting the people around you see whether you’re “immersed” or not and where you’re actually looking with the headset on.

With visionOS on the Vision Pro, Apple is trying to make another mouse-level breakthrough.

Now eye tracking has appeared in virtual reality headsets before. Sony’s PSVR 2 and the Quest Pro are the most memorable recent examples. Apple would never claim it, but the Vision Pro lifts a lot of classic concepts from previous virtual reality experiences, too. Watching video in a virtual environment or interacting with 3D content are things that have been possible in VR for years, and Apple is mostly just doing them at a much higher resolution with greater mobile processing power backing it up. In that way, the Vision Pro, like the Macintosh, shares more similarities with its predecessors than it does differences. It’s just that those differences might matter more.

A Second Macintosh Moment?

History — its own or the industry’s at large — only matters as much to Apple as it helps sell the next product. For the $3,500 Vision Pro, that might be a trickier proposition than it was for the Macintosh. The original Mac had its own eye-popping $2,495 price to contend with, something Apple got around by making a genuinely good product and pairing it with an even better ad campaign. Does a headset work the same way?

Nobody can predict whether or not virtual reality, augmented reality, or spatial computing — whatever ends up being the term — will become as long-lasting as desktop computing, but if it does endure, it’ll require significant effort and insight. The Apple of 40 years ago is not the Apple of today, but the Macintosh is proof that the right ideas, even at a high price, can change people’s minds about even the most intimidating of new technologies. Maybe eye tracking is enough to do that with face computers, too.