The Most Powerful Home on the Block

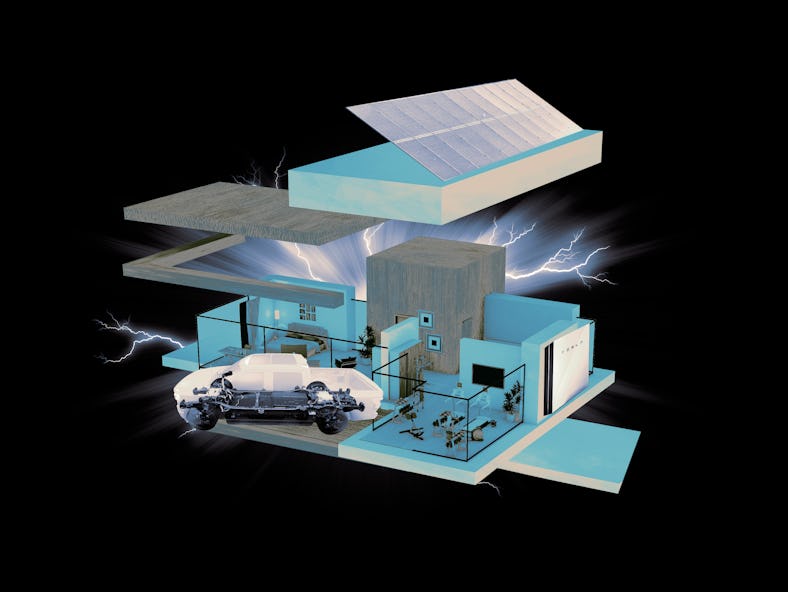

Homes that create and store their own energy are cheaper, safer, and could save the neighbors in times of disaster. They’re also a lot closer than you might think.

This February, Texans encountered a troublingly familiar wintertime blight. Ice storms across the South felled trees and snapped power lines, bringing the state’s electricity grid to its knees. For the second time in three years, winter blackouts left hundreds of thousands of residents sitting through sub-freezing temperatures without power.

The Lone Star State has its own independent power grid to go with its self-reliant mindset. The state’s recent struggles reveal the limits of the way we think about getting electricity. Not everyone is waiting for the power distributors to fix the problem. More Texans are installing solar panels, buying backup batteries for their homes, and driving EVs that offer up their stored energy in case of emergency. When energy moves from power plants and the grid to collectors on the roofs and batteries in the garage, everyone can benefit. Homes and whole neighborhoods become much more disaster-resistant. The lights stay on when the storm passes through. All it takes is a different way of thinking about electricity — and a bit of off-the-shelf tech.

Home Is Where The Grid Is

We flip a switch and the lights illuminate; we push a button and the air conditioner hums to life. Home energy wasn’t always this easy.

Before the advent of electricity, every homeowner was responsible for the actual fossil fuels — coal, kerosene, oil — to power everything, as well as wood and candles to make light and heat. Once electricity from the grid began to do the heavy lifting in our homes, the idea of making your own energy became synonymous with prepping for disaster to going off the grid. But now, old-fashioned self-sufficiency is coming back in a big way, with homes having their own batteries and generating their own solar or wind power. Self-sufficient homes will help us survive heat waves and create a more stable grid for everyone, but the technology behind them also carries serious benefits for the individual — saving you money while protecting your home, and maybe your neighbors, from power outages.

By last autumn, nearly 4 percent of American homes had installed photovoltaic solar panels to harvest energy from the sunshine. And while solar is not cheap, its price has dropped rapidly — from $40,000 for the average residential installation in 2010 to around $25,000 today, before government incentives, paving the way for more homes to get PV.

That’s good news for all of us, says Iain Walker, mechanical staff scientist and engineer at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which researches a full range of future home technologies. Photovoltaic solar panels, like the SunPower Equinox system, are the best way for most people to generate electricity at home. “It's about space and noise,” he says. “With solar power, all you have to do is put on the roof. You can't even see it. It's silent. So you’re not upsetting your neighbors.”

Solar isn’t the only answer, though. With small wind turbines like the Pikasola 400W — those scaled down to a size that could fit in a large backyard — ordinary people can capture the breeze blowing across their property. That solution doesn’t work so well for cities and suburbs, Walker says, but it’s ideal for rural areas where houses are farther apart, and space and noise are less of a problem. “Making rural communities as well as cities more resilient is also a really good idea,” he says.

Many home electricity-makers get to experience the joy of net metering. On a sunny or windy day, when their solar or wind system generates more energy than the home needs, they make money selling energy back onto the grid (and sometimes, like in the most recent Texas heat wave, they can make a seriously sizable chunk of change). While that is a key selling point for home renewables, more Americans are seeking out ways to store their excess energy, too, so they have backup power in case of a blackout.

Walker says emerging technologies could allow this to happen on the scale of a single appliance or home system. Already, several manufacturers like Impulse are testing battery backup in electric stoves to allow for electric cooking during a power outage. Water heaters could have thermal energy storage: Picture a “hot pack” that heats up during the day when ample renewable energy is available. At night, it uses that stored energy, rather than electricity from the grid, to heat a home’s water.

Many people will get battery backup for their entire house, in the form of Tesla’s Powerwall or one of its competitors like the Panasonic EverVolt, LG Energy Solution, or GoalZero 6000X. Basically a big lithium-ion battery for your home, the just-revealed Tesla Powerwall 3 can discharge 11.5 kW of energy, a major upgrade from its predecessor. Powerwalls can be stacked to provide as much storage as one’s home requires and can work with or without solar panels. If you don’t have them, the big battery simply stores electricity when your local electrical costs are low. (Jeff Maguire, a researcher with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, says some people use this idea to engage in “energy arbitrage” — storing power when it’s cheap and selling it back to the grid when it’s expensive to make a little profit.)

Whether or not they buy a big battery for the basement, homeowners of the future will already have a giant backup power supply right there in the garage. Once most Americans drive EVs, the giant batteries in our cars may become the primary way people back up their home power supply. The Ford F-150 Lightning pickup truck is the highest-profile EV to come out with bidirectional charging. Owners can plug into their homes and use the truck’s stored energy to power the house for a day or two.

Some researchers envision extrapolating this idea from your house to the entire country. A huge amount of energy would be stored by a whole country’s worth of EVs. Those plugged in while they’re not being driven could temporarily give some of that juice back to the grid at times when energy demand skyrockets and renewable sources can’t cover the need.

There Glows The Neighborhood

A new approach to energy will make not only our homes but also whole neighborhoods or cities more resilient. Forget the existing model, where one or a few major power plants provide electricity for a huge area, and lots of people lose power if they fail. With home solar panels, small wind turbines, EV batteries, and other technologies able to supply electricity on a smaller scale, we could create a country of “microgrids,” where neighbors share energy and keep the lights on even if the larger grid goes down.

As more homeowners take back control of their energy supply, a growing number may turn to solutions that don’t require electricity at all. Take solar collectors, a decidedly old-school method of channeling the sun’s heat that was around centuries before photovoltaic solar panels. Focused sunlight can be a carbon-free method for cooking food or heating a home’s water supply that’s ideal for Americans living in sunny Southern climates.

It’s also a lot cheaper than the alternative: Building new infrastructure like traditional power plants or transmission lines to fortify or expand the grid is a hugely cumbersome task, Walker says.

Consider again this year’s Texas ice storms. Gov. Greg Abbott said the state produced enough energy for everyone — yet a quarter-million people lost power because power line failures prevented the electricity from getting all the way from the power plant to the people. But underground power lines can cost some $1 million per mile. With a shift from a statewide grid to community-level microgrids, residents could use their energy generation and storage tech to keep the neighborhood lights on even if some power lines or power plants fail.

Homes that make and share their own energy is one side of the coin. The flip side is balancing everyone’s energy use. In sunny California, he says, EV drivers should charge in midday when lots of solar energy is available, not in the evening when people are coming home from work to turn on their ACs, stoves, and appliances. Our EVs and home products will help make this possible, Walker says. “You can get devices now that will monitor the energy price and do it automatically for you. You just say: once it gets [to a certain price] per kilowatt-hour, turn off the EV for the next two hours.”

Such ease is crucial. We have been living in an era of blissful energy ignorance: Beyond paying the electric bill once a month and filling up the tank with 30 seconds of gas, you don’t need to think about energy. The cost of that carefree lifestyle is the damage to Earth’s climate done by the fossil fuels needed to make it possible. As we move to a cleaner energy system, we need smart technologies to make the transition as seamless as possible — and not turn us all into grid managers.

“The idea is to still make sure that the occupants are getting all their needs met,” Maguire says. “They're comfortable, they have hot water, the space is the right temperature — but as much as you can, you move the loads around to also benefit the grid so that everyone wins.”

This article was originally published on