China finds recent water flows on Mars, with big implications for alien life

China's Zhurong rover found geologically recent water on Mars, billions of years after it should have been gone.

Mars was once wet enough to cover its entire surface with an ocean of water hundreds to thousands of feet deep, holding about half as much water as the Atlantic Ocean. However, the most recent epoch of Martian history, known as the Amazonian — the past 3 billion years of the Red Planet— is often considered cold and dry.

Now, in a new study published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances, China's first rover on Mars finds evidence of water there potentially within the past 700 million years.

HERE'S THE BACKGROUND — Recent findings suggest that liquid water might have once flowed across Amazonian terrains, such as the Lyot crater in the northern lowlands of Mars. However, these lowlands are largely covered in dust, making it difficult for orbiters above the Red Planet to detect any water-laden minerals except ancient samples blasted out by cosmic impacts.

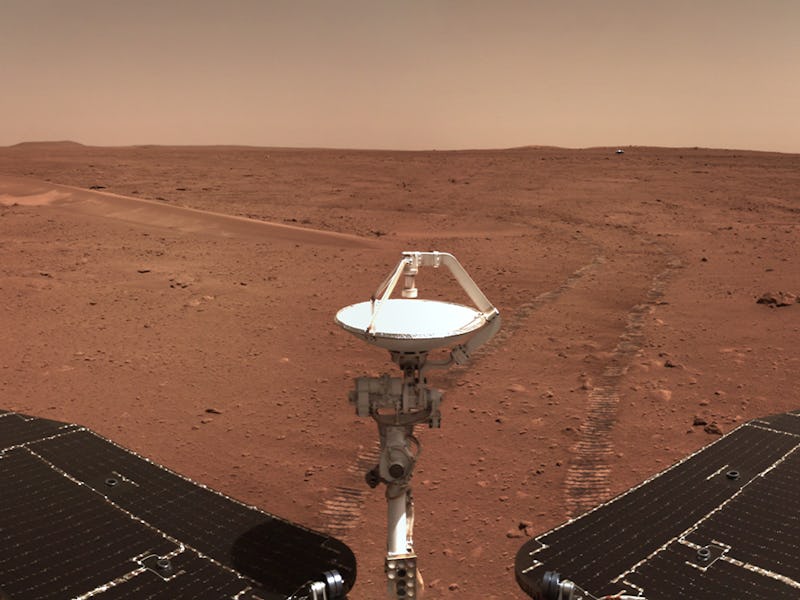

The Chinese National Academy of Sciences researchers analyzed data from the Zhurong rover of China's Tianwen-1 mission to Mars. The rover landed in the northern lowlands of the Red Planet in 2021 — specifically, at southern Utopia Planitia, the largest known crater from a cosmic impact on Mars.

Previous research suggested the area around Zhurong's landing site may be roughly 700 million years old. Several geological features there, such as troughs and ridges, also suggest water may potentially exist just underneath its surface.

The rover examined local rocks with a telescopic micro-imaging camera, an infrared scanner, and a laser that zapped the rock to help sensors probe the chemical makeup of the resulting vapor.

Viking 2 took this photo of Utopia Planitia in 1979.

WHAT DID THEY FIND? — The researchers spotted bright-toned rock they suggested is "duricrust," a hard layer that forms when water deposits minerals at or near the surface. They noted this duricrust may have formed due to a substantial amount of liquid water — either rising groundwater or melting underground ice, set flowing perhaps due to volcanic activity or a cosmic impact. This contrasts with thinner, weaker duricrusts seen at other landing sites, which may have formed due to water vapor diffusing from the atmosphere.

"Liquid water may have been around underground much more recently in Mars' history than previously thought," planetary scientist Tanya Harrison, the director of Strategic Science Initiatives at Planet Labs, did not participate in this research, tells Inverse. "That's exciting from an astrobiological standpoint because on Earth, anywhere there's liquid water, there's generally something that has managed to survive there. So, it gives the potential for a small habitable environment on Mars in the geologically recent past."

However, "while the minerals in these rocks contain hydrated minerals — minerals that contain water molecules in their structure — it doesn't mean there's any liquid water or ice present in this area now, which is important to note," Harrison says. "A large buried ice deposit was discovered a few hundred kilometers to the northwest of Zhurong's landing site a few years ago, but none was found in this area with ground-penetrating radar instruments on two satellites currently orbiting Mars."

Utopia Planitia, seen by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

WHAT'S NEXT? — "Zhurong has a ground-penetrating radar instrument onboard, so it will be interesting to see what that reveals about the upper few meters of the ground beneath the rover along its traverse," Harrison says. "Maybe it will reveal ice at a scale too small for us to have resolved from orbit. That would not only bolster the hypothesis for how these salty rocks formed, but it also gives a source for water ice for future human exploration."

So far, buried ice detected on Mars "tends to be at higher latitudes, where the temperatures and weather conditions aren't great for a human base," Harrison says. "Zhurong, however, is at about 25°N, on par with Miami here on Earth — much warmer in the relative sense than the higher latitudes and with fewer dust storms."

This article was originally published on