Why NASA’s wild new asteroid mission is one of its weirdest endeavors yet

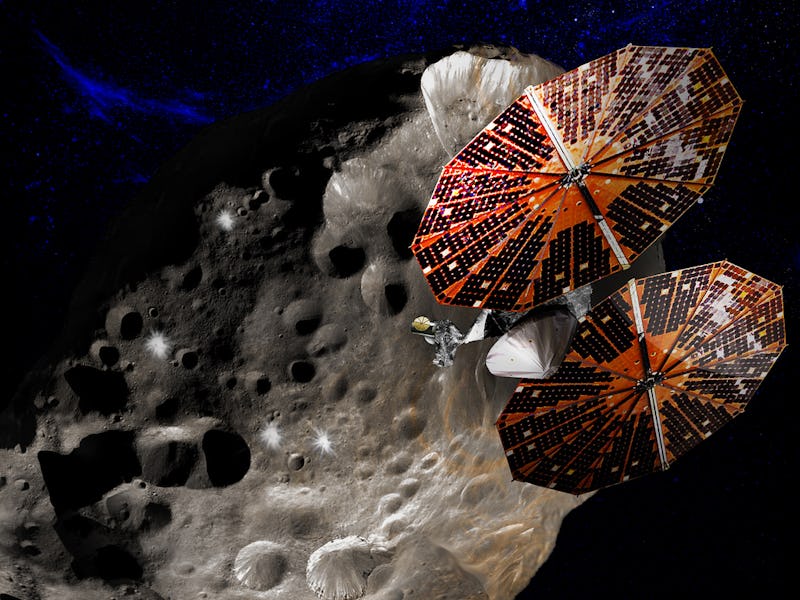

NASA's Lucy spacecraft is on a 12-year mission that could actually last forever.

Lucy, NASA’s mission to the Trojan asteroids of Jupiter, is on a very long and complicated space odyssey.

The spacecraft will fly an unprecedented course that will take it out in front of the gas giant for relatively rapid flybys of four asteroids, and then back to Earth for a gravity assist maneuver, before heading back out to space behind Jupiter to visit more space rocks.

All told it will be a 12-year mission for Lucy — one that could be extended past the official end date in 2033 — but will ultimately end with Lucy, fuel spent, flying a loop between the inner and outer Solar System, potentially for thousands of years.

It launched Saturday morning, October 16. This is what you can expect next.

Lucy spacecraft propulsion

While massive 24-foot-long solar panels will power Lucy’s instrumentation, its maneuvering and course corrections will be driven by a set of 14 hydrazine thrusters made by Aerojet Rocketdyne — eight MR-103J thrusters and six MR-106L thrusters.

The company is also providing the single Centaur engine powering the second stage of the Atlas 401 V rocket that will set Lucy on her initial course. This course will see the spacecraft make two gravity assist flybys of Earth to build up speed for its six-year journey to the first set of Trojan asteroids it will visit — with a flyby of the main asteroid belt space rock along the way.

Lucy mission trajectory

Viewed from a perspective above the Solar Systems orbital plane, Lucy’s flight plan looks like a complex figure-eight twisted into a pretzel.

After launch, the spacecraft will swing around Earth twice for a gravity assist before passing by an asteroid in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter before finally reaching the swarm of asteroids in front of Jupiter, known as the L4 point Trojan asteroid swarm.

A diagram of Lucy’s pretzel-like flight path and flyby targets.

After flying by a series of course asteroids there, Lucy will loop back in towards Earth for another gravity assist before shooting back out toward Jupiter’s orbit, this time visiting the swarm of Trojans that trail the gas giant, the L5 point Trojan asteroid swarm.

Lucy’s initial trajectory with its two Earth gravity assists is hardly unique, according to Jeremy Knittle, Lucy Trajectory Optimization Lead at KinetX, a NASA contractor that helped developed the Lucy flight plan. Many spacecraft have made use of Earth's gravity assists to get out to the outer solar system or closer to the Sun.

What’s special and new about Lucy’s flight path, Knittle tells Inverse, is relatively rapid, sequential flybys of multiple asteroids, and the demands that places on the rest of the flight plan to avoid using too much fuel for course corrections.

“I don't think there's been a lot of trajectories or any really before where we have strung together multiple high-speed flybys,” he says, with two of the first flybys coming just 27 days apart.

That forced Knittle and other flight engineers to solve Lucy’s entire mission flight plan as a whole, he says, with each segment exquisitely sensitive to changes in the rest. To make the whole thing work, Lucy will have to fly through a very narrow corridor of coordinates from the very beginning.

Lucy is undertaking a spiraling mission.

“Things that we're doing in the next year or so after we launch really are going to line us up for things that are happening six or seven years later,” Knittle says.

If Lucy misses its marks early on, “it's not that we wouldn't be able to execute the rest of the mission — it's just you're going to pay a pretty high penalty because you're going to kind of be zig-zagging back and forth,” he says.

Zig-zagging means burning fuel, and burning fuel could shorten Lucy’s lifespan. This would be a shame, Knittle says, because the other unique thing about Lucy’s flight path is that, once well executed, it will remain remarkably stable for years to come.

As long as the spacecraft has fuel, the team could apply for an extended mission and visit more Trojan asteroids. For now, Lucy is intended to visit seven Trojans as well as another asteroid.

A visualization of Lucy’s 12-year mission flight path to the Jupiter Trojan asteroids.

“It really shouldn't take much propellant or much maneuvering for us to fly by more and more asteroids,” Knittle says. “We'll just keep going out to the L4 cloud, back into Earth, back out the L5 cloud, back into Earth.”

And will remain true even after Lucy finally exhausts its fuel and even its extended mission comes to a close. The complex pretzel orbit, once set, will be Lucy’s permanent trajectory, a loop to the outer solar system and back by Earth that could remain stable longer than human civilization.

“It will last much longer than our ability to predict,” Knittle says. “We could run it out for literally hundreds of thousands of years, and to our level of ability to predict that far out, it will look exactly the same.”

Lucy mission targets

The asteroids targeted for flybys during NASA’s Lucy mission.

At just 2 to 3 miles in diameter, Lucy’s first target, Donaldjohanson, is the smallest of the space rocks the spacecraft will fly past and the closest. Donaldjohanson orbits the sun in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. It will take Lucy more than two years after this first flyby to reach the first of its Trojan asteroid targets.

Donaldjohanson is named after the paleoanthropologist who discovered the fossilized skeleton of a human homing ancestor in 1974. The scientist Donald Johanson named the skeleton Lucy, after the Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamond,” and NASA named Lucy the spacecraft after Lucy the Australopithecus because the probe will be exploring the Solar System’s origins by studying the ancient Trojan asteroids.

Lucy’s next four targets follow Jupiter’s orbit but fly ahead of the big planet at the L4 Lagrangian point. It’s a space where Solar and Jovian gravity balance out, allowing the Trojans to maintain a constant location relative to Jupiter. The L4 Trojan targets Eurybates, Polymele, Leucus, and Orus are all named for characters in The Illiad, and range in size from the 13-mile diameter Polymer to the 40-mile diameter Eurybates.

In January 2020, the Lucy team used images from the Hubble Space Telescope to confirm that Eurybates has its own small satellite, a much smaller orbiting space rock less than a mile in diameter. The satellite, dubbed, Queta, takes its name from the late Mexican track and field athlete Norma Enriqueta “Queta” Basilio Sotelo.

Lucy’s final scheduled encounter is a twofer: The asteroids Patroclus and Menoetius in the L5 group of Trojans trailing Jupiter are a binary pair, tightly orbiting each other just some 400 miles apart. The largest of the asteroids Lucy will visit are Patroclus, around 70 miles in diameter, and Menoetius at around 65 miles.

Lucy mission timeline

After launch, Lucy will embark on a long journey with many years of silence, punctuated with brief milestones of scientific discovery as it makes its eight scheduled flybys:

- April 2025: Lucy will fly past DonaldsonJohnson in the main asteroid belt.

- August 2027: Lucy encounters Eurybates, the first of the L4 Trojans leading Jupiter.

- September 2027: Lucy flyby of Polymele

- April 2028: Lucy flyby of Leucus

- November 2028: Lucy will visit its last L4 Trojan, Orus, and then fly back toward Earth for a gravity assist to swing back out toward Jupiter to visit the L5 Trojans.

- March 2033: Lucy encounters the L5 Trojans Patroclus and Menoetius.

This article was originally published on