Why NASA's return to Venus could help save the Earth

The space agency is launching two missions to study Venus' atmosphere and geological history.

Astrobiologist David Grinspoon had been conditioned for rejection. He’s submitted Venus mission proposal after Venus mission proposal to NASA for years on end, each landing with a thud. So when he heard the news that his mission DAVINCI+ got selected by NASA on Wednesday, Grinspoon was in disbelief.

“I did a lot of screaming and jumping up and down,” Grinspoon tells Inverse. “I scared my dog.”

On Wednesday, NASA selected both DAVINCI+ and another Venus mission, VERITAS, to study the planet’s atmosphere and geological history. It will mark a return to Venus after decades away.

By returning to Venus, it could answer questions both intriguing, like if Venus ever had the right conditions for life, and existential, like if Venus is a vision of our future.

Why are we going to Venus now?

NASA sent several missions to Venus in the 1960s and 1970s, but the last one, Magellan, arrived at Venus in 1989 and shut down in 1994. Since then, the agency hasn’t launched a dedicated mission, instead putting a laser focus on Mars.

Part of this is due to Venus’ unusual nature, where temperatures around 900 degrees Fahrenheit have felled landers within a couple of hours. Thick clouds make orbiters work extra hard to study the surface below.

“There have been a number of reasons why we've been neglecting Venus but hopefully that's all changing,” Grinspoon says.

Mars has proven an important laboratory for understanding the early Solar System and Earth’s origins, but the picture is incomplete without Venus. The neighboring planet shares a lot of similarities with Earth, being about the same size and potentially having a watery past.

That watery past ended in a hellish series of poorly understood climate events that left the planet as the hottest world in our Solar System thanks to a thick atmosphere of carbon dioxide. Venus could serve as a real-life lab to study the effects of climate change on planet like Earth.

“We think Venus used to be a lot like Earth,” Grinspoon says. “But something happened to its climate, geology, and its ocean that seems to make it no longer Earth-like and no longer able to support life.”

That's why Venus often serves as an eerie vision of what Earth's future may look like if we don't get greenhouse gas emissions under control.

“Venus is a natural laboratory to study climate change and to sort of push our climate models to the limit,” Grinspoon says.

Venus’ comeback tour

Scientists, as well as Venus enthusiasts, have been calling for a mission to Venus for years.

Planetary scientist Paul Byrne of North Carolina State University was hoping that NASA would select one mission to Venus, and was beyond ecstatic to find out that the space agency selected two missions instead.

“It hasn’t sunk in yet,” Byrne tells Inverse. “It gives us a very clear path forward in terms of how we're going to explore and understand Venus in the coming decades.”

The two missions were selected from a batch of four possible missions selected by NASA’s Discovery Program in 2020, and are expected to launch between 2028 and 2030.

The missions aim to understand how the planet formed and evolved over time, and if it ever had an ocean.

The DAVINCI+ mission, which stands for Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging Plus, will drop a spherical probe into the Venus’ atmosphere to measure the chemical makeup of each layer. It will also have an orbiter component that will capture ultraviolet and infrared images of Venus looking for signatures of present-day volcanism over the course of a Venusian year (225 Earth days).

“I'm looking forward to the high-resolution images of the surface of Venus. They will reveal features that we didn't even think to look at,” Byrne says. “It's going to revolutionize what we think Venus looks like.”

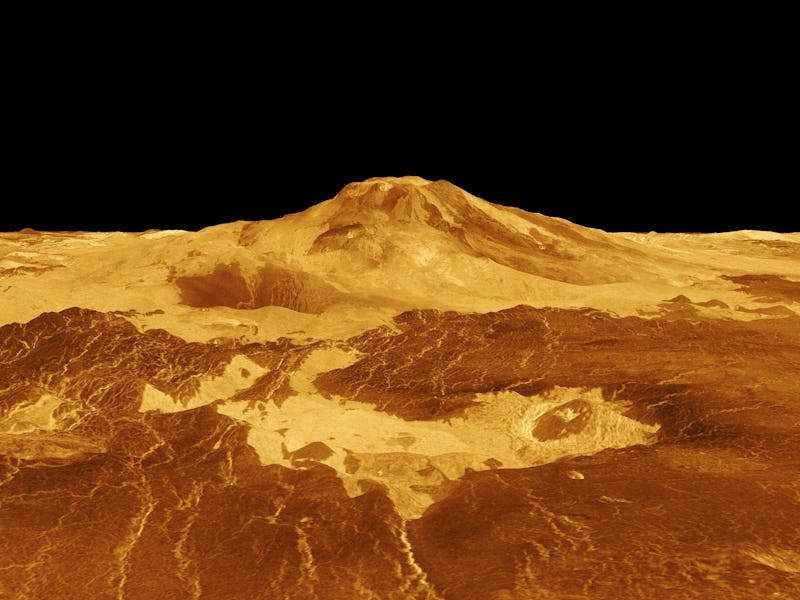

The second mission VERITAS, which stands for Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy, will map the geological features of Venus.

The spacecraft will create 3D topographic maps of the planet’s surface and measure its gravitational pull. The purpose of understanding Venus’ geological history is to determine why the planet, which started off very similar to Earth, developed in a much different way over time.

Venus may have started off as an Earth-like planet, even capable of supporting life.

Are we searching for life on Venus?

In September 2020, a potentially groundbreaking discovery on Venus claimed to provide evidence for potential life being harbored in Venus’ clouds.

A group of scientists detected traces of phosphine gas in Venus' atmosphere. Phosphine is considered a biosignature gas on Earth, meaning that it is typically produced by a living organism.

But the results were met with skepticism, with some arguing that the signal wasn’t produced by phosphine and that it is unlikely produced by microbes that live in the clouds of Venus. DAVINCI+ could help researchers figure out whether the phosphine detected there was real or an illusion.

However, Grinspoon doesn’t think the phosphine debate played into the Venus mission selection.

“I actually don't think that was a huge factor. It's true that there was a story in the media recently and it gave us some visibility,” Grinspoon says. “The good arguments for these missions to Venus was never dependent on the discovery of phosphine.”

The two missions will complement each other, helping scientists put together parts of Venus’ past in order to better understand its future, and possibly the future of Earth.

“Venus is long overdue,” Grinspoon says. “I’m excited to get to work and make it happen.”