Are viruses alive? Virologist chart hints at a larger debate around Covid-19

The science behind virus evolution.

SARS-CoV-2 is a virus that causes Covid-19. It's just one of the 219 — and counting — viruses that can infect humans. Three to four new species are found every year. Overall, the viruses that make us sick represent just a small fraction of the virus world. In the ocean, for example, there are nearly 200,000 viruses.

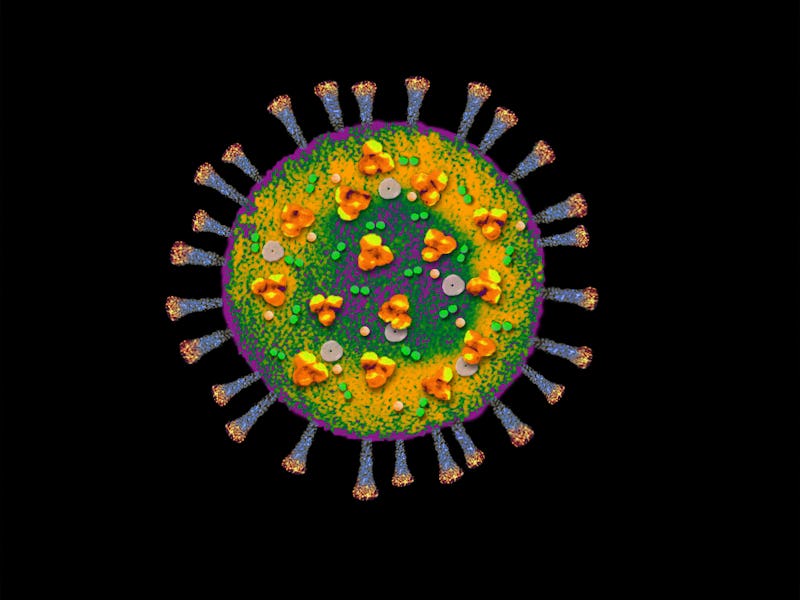

In essence, a virus is a collection of genetic code surrounded by a protein coat that can only replicate within a host organism. In the ocean, a virus might live inside cyanobacteria. On land, they can live inside us.

When one of those 219 viruses infects us, it feels like it emerges out of thin air. In reality, viruses' existence is a story of perplexing evolution, rooted in the natural world.

To better understand viruses, Inverse spoke with virologists about where viruses come from, why viruses can make us sick, and why SARS-CoV-2 definitely didn't come from a lab.

What is the evolutionary origin of viruses?

The answer to how viruses first came to be is still being debated by experts. But a few details give us an idea of what the earliest viruses looked like.

Viruses might start as "rogue stretches of nucleic acid" — either DNA or RNA — that split off from other cells, Paul Turner, a biology and ecology professor at Yale University, tells Inverse.

From there, viruses may evolve the ability to move between cells, Turner explains. "This could happen any day of the week," Turner says.

Other viruses may also be three or four billion years old, if they evolved around the same time as the first cellular life, as many scientists believe. It's hypothesized that, for billions of years, viruses may have survived by adapting to live in different species on Earth.

Viruses don't metabolize themselves, instead relying on the cells of the organisms they infect. So even when resources are slim, viruses save energy by bumming it from their hosts, and weather the storm.

While cellular life probably had one common ancestor, viruses may have had several ancestors, says Siobain Duffy, a virologist at Rutgers University. Because some viruses are made up of RNA, and others DNA, this suggests they likely didn't emerge from the same ancestor. And since RNA emerged before DNA, it's possible that viruses are even older than cellular life.

Are viruses alive?

Viruses reproduce, evolve, and move between cells. But does that mean they're alive?

"Almost all virologists hate this question," Duffy tells Inverse, "because it’s completely irrelevant for the work that we do."

When it comes to biology, it's difficult to come up with a definition of "life" that doesn't have some kind of caveat, Duffy explains. So rather than a fine line between living and non-living, Duffy says, it's more of a "blurry schmear."

Viruses are "real, biological things" which have evolved just like bacteria and animals, Duffy explains. But viruses are simpler than microscopic organisms: They use the cells they inhabit to carry out basic functions, like making proteins. Essentially, they're parasites.

“In a way, they’ve just streamlined the process,” Duffy says. Fleas and lice, for example, are also really good at exploiting their hosts to survive.

Ultimately, it's a matter that's far from settled.

“It doesn’t matter if viruses are alive," Duffy says. "They influence life tremendously.”

What natural factors are needed for a new virus to emerge? — Many natural factors can make a virus successfully emerge, Turner and Duffy explain. A virus doesn't necessarily have to tick all the boxes; one factor or a combination may do the trick.

- Mutations: When a virus has inhabited one animal, it can mutate in a way that makes it viable for the virus to move into another host. For example, a bat may have a virus that mutates in a way that makes it possible for the virus to persist in a human. If that bat encounters a human, the mutated virus can infect the human.

- Host defenses: If an animal isn't able to defend itself against a virus naturally, then the virus benefits: It's more difficult to remove it, so it can continue reproducing inside that host.

- Transmission: Thorough droplets, feces, oral transmission, or surfaces called fomites, a virus can jump from one host to the next. That allows it to keep growing and spreading.

- Epidemiology: When a successful virus spreads quickly from host to host, it can ignite an epidemic or pandemic.

When it comes to a virus moving from an animal to a human, however, there are other factors that contribute — like the relationship between humans and animals.

How does the relationship between animals and people contribute to viruses? — People encroaching into natural territories can amplify the above factors because it gives viruses an opportunity to make the leap to humans.

Within one host, a virus may have a ton of variation. So within just a few mutations, it can change enough to infect another host, like a human. Once that happens, it's all downhill.

“On the inside, a mammal cell is pretty similar to another mammal cell,” Duffy explains. So it’s important to “crack the code on the outside of the cell.”

As humans poach and hunt, there are more opportunities for a mutated variation of a virus to "jump" into humans.

What does it mean to say SARS-CoV-2 has a "natural origin?" — Scientists don't believe that the virus that causes Covid-19, called SARS-CoV-2, was created in a lab. It wasn't released or accidentally let out.

A number of studies have proved its natural origin. Scientists also know it didn't emerge from a lab because that's actually happened before — and the virus we're dealing with now doesn't fit the mold.

In 1977, USSR scientists (maybe accidentally and maybe not) released a strain of influenza that wasn't supposed to enter the real world. By studying that flu strain, scientists could tell that the timeline was off: It shouldn't have existed at that point it time.

But with SARS-CoV-2 there's no sign that the virus was created by stitching together other viruses —it evolved as usual.

“It’s definitely not a lab escape," Duffy says. "This is not a human-modified virus in any way or a human-captured virus that escaped."

“It’s easy to pick out what doesn’t belong, and that’s not what’s going on here.”

This article was originally published on