We finally know when the Webb Telescope's first color images will arrive — here’s what to expect

“We’re just human, and we cannot predict what the universe is going to tell us.”

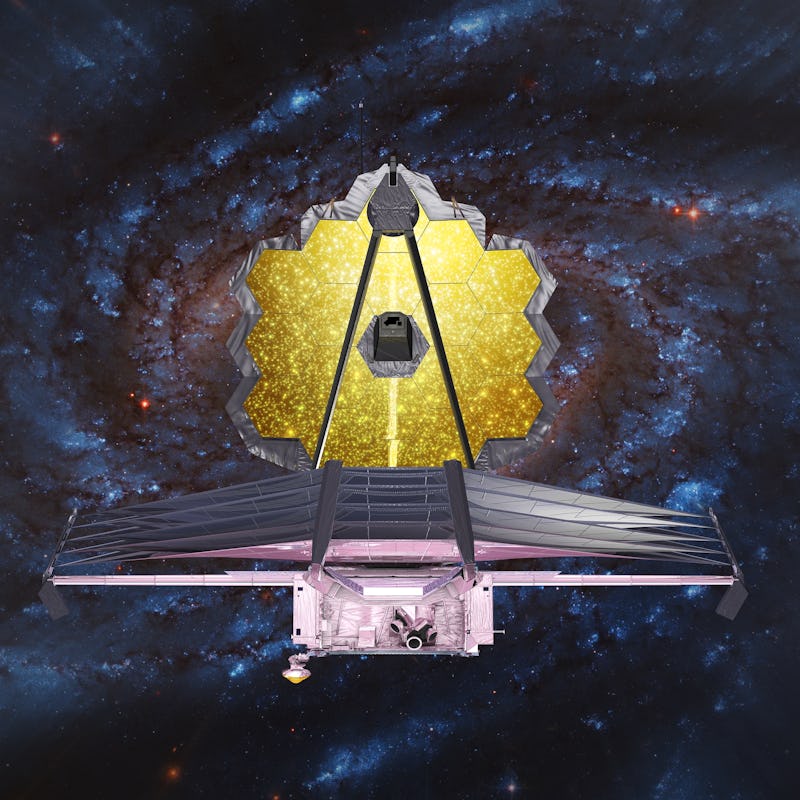

It’s the moment we have all been waiting for: The James Webb Space Telescope will make its first scientific observations of the universe in the coming weeks. The first full-color images will drop on July 12, 2022, along with spectroscopic data.

This is the crescendo moment in a scientific symphony that has been tuning up for the last two decades.

What the images will show is somewhat a mystery —so Inverse spoke to Klaus Pontoppidan, Project Scientist with the Webb Mission Office at the Space Telescope Science Institute and Technical PI for Webb’s Early Release Observations, to try and glean some clues to what they will reveal.

“The purpose of the first images, what’s called the early release observations, is really to demonstrate to the world that we are ready to do science,” Pontoppidan tells Inverse.

“It’s also really a celebration of getting to this point.”

A few test shots from the Webb.

What’s New — On Sunday, July 12, the Webb team will release an unconfirmed number of full-color images based on observations by two of Webb’s four science instruments: the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI).

The Webb’s two other instruments, the Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) and the Fine Guidance Sensor/Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (FGS/NIRISS) don’t capture photo-like images of the universe. Instead, they sort incoming light from distant objects into distinct wavelengths. Scientists can then use these data to measure the temperature and chemical makeup of those objects.

“We will release the scientific data from those observations as well — not just the color JPGs, but also the actual quantitative data — to the astronomical community,” Pontoppidan explains.

What can we expect to see in those first images and data? The Webb team is keeping specific spoilers under wraps, but they’ve offered a few (very broad) hints…

James Webb Space Telescope first targets

Webb vs Hubble: The left image shows what the Carina Nebula looks like in visible (Hubble), versus infrared, also taken by Hubble (how Webb sees the universe). The infrared image shows more stars.

Webb’s first round of observations will target specific cosmic objects drawn from a list written months ago.

The list was composed by a committee that included members of NASA, the European Space Agency, the Canadian Space Agency, and the Space Telescope Science Institute. The goal is to show off the capabilities of each of Webb’s four instruments, while also demonstrating each of the telescope’s main science themes:

- The early universe

- The evolution of galaxies

- The lifecycle of stars

- Exoplanets

Pontoppidan confirms that means that we can expect the early release observations to include at least four targets along these lines.

While the list of targets was prepared in advance, the Webb team had no way to predict what part of the sky the telescope would be able to see when the big day arrived. The final list of targets, which we’ll see in the first full-color images on July 12, were selected from the larger list because they’re currently in the Webb’s field of view.

It’s going to be beautiful.

Here's the Background — The James Webb Space Telescope launched in December 2021, and the observatory has spent the last six months preparing for its July 12 debut.

That process included deployment, aligning the telescope’s mirrors, and calibrating and testing all four science instruments.

“There are 17 science modes among all the 4 science instruments. There can be imaging, different kinds of spectroscopy, and different kinds of coronography (where we get rid of the light of bright stars so we can see something faint next to it, like a planet). Those all have to be checked out, and made ready for science,” Pontoppidan says.

“That takes time.”

In the last few months, the Webb has sent home a few preliminary images, including one of the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way, and of nearby bright stars. While pretty, these were taken to verify that its mirrors were aligned properly. They were the space telescope equivalent of quick test snapshots, not the full-color, detailed images the Webb team will release on July 12.

“We’re just human, and we cannot predict what the universe is going to tell us.”

Pontoppidan says that over the next few weeks, the Webb will collect the observations it needs to produce its first science images. But, he says, some of the observations may have already happened.

It takes weeks to turn raw data from a space telescope into information that scientists can use — and images of the universe that the rest of us can fully appreciate. Among the thirty-or-so people preparing JWST’s first observations for release are engineers, scientists, and graphic artists: It’s their job to translate infrared wavelengths into colors human eyes can see.

Pontoppidan compares it to translating a poem written in another language:

“There are some standard rules that we follow. For instance, in the visible, a redder color has a longer wavelength, a lower frequency, lower energy, than a blue color,” he explains.

“So there's an order to it. Within that, there are some tweaks you can make, such as adjusting saturation and exposure. This is all done with Hubble images, too.”

“It takes a little work to get the poetry across,” he adds.

What to expect from the Webb Telescope’s first data

The Large Magellanic Cloud could be a target for Webb’s science observations.

The Webb telescope’s first science targets were chosen to demonstrate what the telescope can do, not necessarily to collect data for any specific scientists’ research. But Pontoppidan expects scientists to make good use of the spectroscopic data.

“We would expect people to download those and use them for science,” he says.

The main purpose of the early release observations is to mark the end of Webb’s six-month preparation for first light and the beginning of the telescope’s science mission. They’ll also offer a preview of what Webb’s first year of science observations will look like, the data the telescope will collect, and the types of things it might help astronomers discover about the universe — from the most distant 13-billion-year-old galaxies to planets in our own Solar System.

“We’re not going to have time to do science with these images, but I think we’ll get a real sense of some of the things that might be discovered in the next year,” Pontoppidan says.

What’s Next — By the time we see the first real images from the Webb on July 12, the telescope may already be busy doing actual science.

Scientists around the world have applied for slices of the Webb’s observing time, and the first year of the telescope’s schedule is already packed. And although its main science goals are clearly defined, we know that the distinct discoveries will be incredible.

That’s mostly because the Webb’s images will be so much sharper than anything we’ve seen from previous infrared telescopes, like NASA’s now-decommissioned Spitzer Space Telescope (RIP, Spitzer).

Pontoppidan compares it to seeing the world without glasses, and then putting them on: The sharper focus reveals details that weren’t visible before. In Webb’s case, those details will almost certainly include stars, galaxies, and other structures that weren’t visible before.

“The universe is huge and varied, and we’ve only scratched the surface of what's there,” Pontoppidan says.

“I think anybody would say we’re just human, and we cannot predict what the universe is going to tell us.”

This article was originally published on