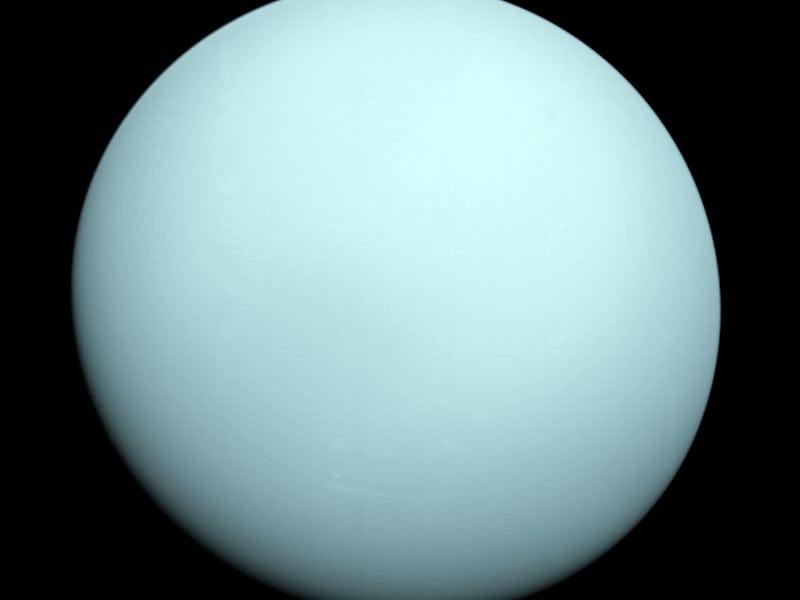

A new look at Voyager’s Uranus flyby reveals something unusual about the planet

The spacecraft witnessed something extraordinary.

Over 30 years ago, NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft flew over the hot, dense world of Uranus, getting as close as 50,600 miles to the planet’s cloud tops.

At the time, the data collected offered scientists an unprecedented look at the ice giant of our Solar System, revealing two new rings and 11 new moons, as well as chilling temperatures that dip below 353 degrees Fahrenheit.

However, what the scientists didn’t know at the time was that Voyager 2 had also witnessed something quite extraordinary over Uranus.

A team of scientists took a new look at the data collected from Voyager’s Uranus flyby and discovered that the spacecraft had actually flown right through a plasmoid. Plasmoids are a giant structure of a planet’s magnetic field, and they can also strip a planet of its atmosphere.

The new findings were detailed in a study published in the Geophysical Research Letters, and offer a new insight into Uranus’ magnetic field.

Voyager 2 launched on August 20, 1977, and began its unique journey into interstellar space. But before it did that, the spacecraft had some close encounters with the planets of the Solar System.

Voyager 2 did a flyby of planets of the Solar System before heading into interstellar space.

Voyager 2 was scheduled for a rendezvous with Uranus on January 24, 1986. The spacecraft beamed down thousands of images, and a host of scientific data and measurements of the planet, its atmosphere, and magnetic environment.

Uranus is an odd planet. Its spin axis is tilted by 98 degrees, which means that it spins entirely on its side unlike any other planet in the Solar System. As a result, the axis of its magnetic field points 60 degrees away from its spin axis.

So when the planet spins, the magnetosphere or the space carved out by its magnetic field, sort of wobbles along the way like a football, according to a statement by NASA.

The scientists behind the new study wanted to investigate the planet’s odd magnetic field further, so they began by looking back at the data gathered by Voyager 2.

Scientists took a closer look at 34-year-old data on Uranus.

As they reexamined the data with fresh eyes, and more precision than before, they found a small ‘squiggle.’

That tiny distorted line was a plasmoid. Plasmoids are a sign that a planet is being stripped of its atmosphere, as these giant bubbles of plasma are sucked from the atmosphere, and hang off the end of a planet’s magnetic field that is blown by the solar wind, also known as magnetotail.

The discovery marks the first time that plasmoids were discovered at Uranus. It lasted for only 60 seconds of Voyager’s 45-hour-long flyby and therefore appeared as a tiny blip in the data.

The process, however, is not unique to the planet. Planets like Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, and even Earth are losing their atmosphere, as particles escape their planetary grip and float off into distant space.

This process is caused by the planets’ magnetic fields.

A very extreme case of atmosphere escape is Mars. Scientists believe that the now dry and desolate Red Planet may have once looked very different, and possibly even hosted some form of life. But over 4 billion years of leaking into space finally took a toll on the planet.

"Mars used to be a wet planet with a thick atmosphere," Gina DiBraccio, a space physicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center and project scientist for the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) mission, said in the statement. "It evolved over time to become the dry planet we see today."

However, it’s not clear how Uranus’ atmospheric escape has affected the planet thus far as scientists only got a tiny glimpse at this process.

"Imagine if one spacecraft just flew through this room and tried to characterize the entire Earth," DiBraccio said. "Obviously it's not going to show you anything about what the Sahara or Antarctica is like."

But the newly revealed discovery does help narrow down new questions that scientists should be asking about Uranus.