NASA’s Voyager engineers are devising clever ways to preserve our farthest mission

The mission is far from over.

Despite recent headlines, NASA’s venerable Voyager craft isn’t shutting down quite yet — but in two months, the team that manages the iconic mission will make decisions about what to do with dwindling power.

Earlier this month Scientific American published a story about the aging spacecraft, catching the attention of several outlets who proceeded to cover the mission team’s ongoing mitigation efforts as though Voyager was entering a somber new phase.

Fortunately, that’s not entirely true. Yes, Voyager 1 and 2 are “powering down.” But through this action, NASA is rejuvenating the 45-year-old heritage mission. The Voyager team will convene later this summer to make new decisions, too.

“The headlines I see are that it’s turning off, and that’s not what’s happening,” former Voyager 2 mission team member Heidi Hammel tells Inverse.

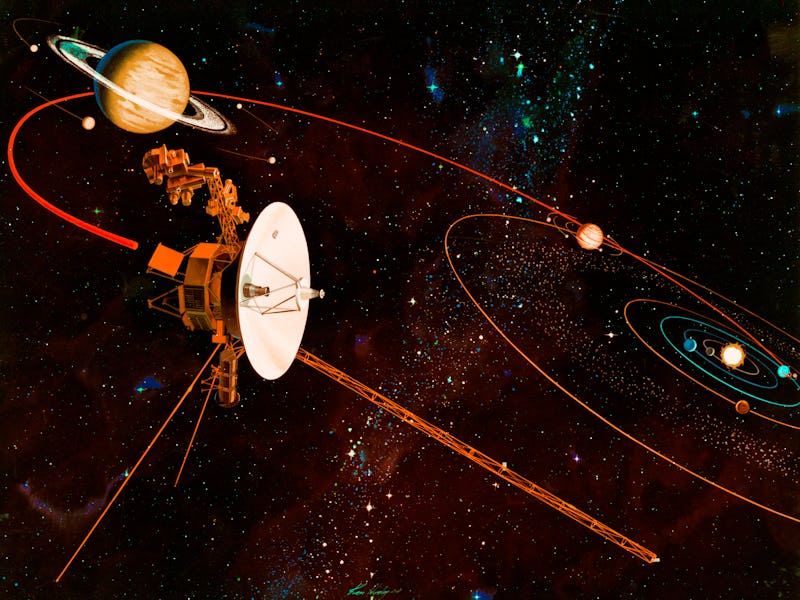

Under the hood — The twin spacecraft are now each flying more than 12 billion miles away from the Sun, and with every moment that passes, they further enter into a difficult scenario: an energetic output loss of about four watts per year, according to a spokesperson from the Voyager press office at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

They need energy to warm themselves up, because soaring far away from the Sun comes with a price. Without artificial heat for their spacefaring hearth, they cannot run their instruments.

Over the last several decades, the team has confronted their philosophical dilemma and made a bold decision: By turning off the heaters to some of their instruments, they direct the depleting resources to keep powering the rest of the spacecraft’s instruments and hope for the best.

“There’s a plan to strategically conserve every last bit of power in the radioisotope thermoelectric generators; those are the things that give us the power,” Hammel says. “There’s only three of them [per spacecraft] and they do slowly decay with time.”

The gambit worked, extending the mission lifetimes, leaving “those instruments that truly can still do work out there in interstellar space” able to explore this vast unknown at the edge of the Sun’s protective sphere of influence.

And there is still so much that scientists want to learn. For instance, does the Sun make a massive bubble that’s shaped like a croissant, or does it have a tail like a comet? Is the Sun’s radiation tickling deep-space particles, or might the great beyond be exerting strange influences on the solar wind? Voyager 1 and 2 are in the thick of it, sailing outwards in different directions and both flying through interstellar space. Scientists want them to keep going.

“To actually be tasting the cosmic rays and the charged particles — the remnants of the solar magnetic field — there’s no other way to do that,” Hammel says.

What’s next — The decades of time that blessed Voyager to reach interstellar space are also their curse. It’s a bittersweet exchange.

A JPL representative tells Inverse that both spacecraft have less power to “spend,” a perpetual condition that has been the case since they launched in 1977. In 1989, the mission turned off Voyager 2’s cameras to save energy.

“The imaging subsystem was one of the first to be turned off to conserve battery power, because once we were past Neptune, there’s very little to see,” Hammel says. “At some point, they turned Voyager 1 around and took the picture of the Solar System — the ‘Pale Blue Dot’ — but there was really no science to be done with the imaging system. So they were turned off.”

The team turned off instruments that were part of Voyager’s planetary missions.

What’s changed over the last three years is that, now, Voyager is turning off the heat source to the instruments the team had selected to remain operational for the current interstellar mission. In 2019, they shut off the heat source to Voyager 2’s cosmic ray subsystem (CRS) instrument, but this apparatus isn’t “off”, CRS is still sending back data.

Voyager is entering a more “aggressive” campaign to save energy, channeling Voyager’s diminishing nuclear energy away from some instruments so that others can continue running. The team is thrilled, in fact, that each of the turned-off instruments across both spacecraft, like CRS, is still operating well. That’s in spite of them now getting exposed to frigid temperatures much lower than what they experienced during testing almost half a century ago.

The Voyager Science Steering Group will meet in August to make new decisions about how to manage their power, the JPL representative says. Engineers will propose creative solutions so that Voyager’s team back on Earth can stay connected to their high-flying cosmic kites.

This article was originally published on