30 years later, Voyager reveals new details about one of the Solar System's strangest planets

There’s nothing like looking at 30 year old data with fresh eyes.

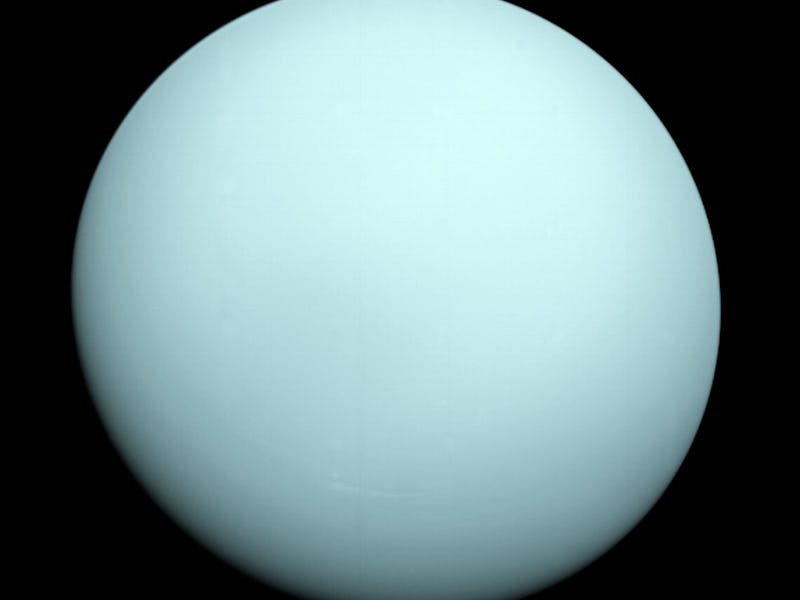

On January 24, 1986, Voyager 2 flew by the seventh planet from the Sun; Uranus.

The spacecraft beamed down thousands of images, and a host of scientific data and measurements of the planet, its atmosphere, and magnetic environment.

At the time, the data collected offered scientists an unprecedented look at the ice giant of our Solar System, revealing two new rings and 11 new moons, as well as chilling temperatures that dip below minus 353 degrees Fahrenheit.

INVERSE IS COUNTING DOWN THE 20 MOST UNIVERSE-ALTERING MOMENTS OF 2020. THIS IS NUMBER 3. SEE THE FULL LIST HERE.

This year, a team of scientists took a new look at the data collected from Voyager’s Uranus flyby and discovered the spacecraft had actually flown right through a plasmoid — a giant structure of a planet’s magnetic field, one which can strip a planet of its atmosphere.

The yellow arrow points to the Sun, the light blue arrow marks Uranus’ magnetic axis, and the dark blue arrow marks Uranus’ rotation axis.

Of all the planets in the Solar System, Uranus is quite odd.

The planet’s spin axis is tilted by 98 degrees, which means that it spins entirely on its side unlike any other planet in the Solar System. As a result, the axis of its magnetic field points 60 degrees away from its spin axis.

So when the planet spins, the magnetosphere, or the space carved out by its magnetic field, sort of wobbles along the way like a football, according to NASA.

A false-color image of Uranus' rings, captured by Voyager in 1986.

As the scientists reexamined the Voyager data with fresh eyes, they found a small ‘squiggle.’

That tiny distorted line was a plasmoid. Plasmoids are a sign that a planet is being stripped of its atmosphere. These giant bubbles of plasma are sucked from the atmosphere, and hang off the end of a planet’s magnetic field as it is blown by the solar wind. This phenomenon is also known as magnetotail.

It lasted for only 60 seconds of Voyager’s 45-hour-long flyby, so it appeared as a tiny blip in the data — so tiny it took scientists more than thirty years to spot it.

The discovery marks the first time plasmoids have been detected at Uranus, and gives scientists a better understanding of the processes that govern this mysterious icy giant.

INVERSE IS COUNTING DOWN THE 20 MOST UNIVERSE-ALTERING MOMENTS OF 2020. THIS IS NUMBER 3. READ THE ORIGINAL STORY HERE.