Once a year, we get closer to NASA's Voyagers — here's why

They aren't going backward — we're just going forward.

NASA’s two Voyager spacecraft are on a one-way trip in interstellar space on their way out of the Solar System.

The groundbreaking missions launched in 1977 to send two probes into the outer Solar System, collectively viewing Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. Voyager 1 successfully finished a Saturn flyby in 1980 and swung high above the plane of the Solar System, while Voyager 2 took advantage of a rare alignment to see Uranus and Neptune up close, the only spacecraft to do so yet — though scientists are clamoring for a deeper dive into Uranus.

The spacecraft, still fortuitously operational, continue to send back data. But every year comes an orbital quirk. Even though the Voyagers are rapidly leaving our Solar System, there’s a period where the spacecraft are a little closer to us once a year for a few months.

For example, distance data from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory shows Voyager 2 was at 130.05518 astronomical units (Sun-Earth distances) from our planet on February 20. Yet the spacecraft will be at 129.72179 astronomical units (Sun-Earth distance) by June 2 before drawing away again.

The reason is the Earth’s movement rather than the spacecraft: “When Earth is on the same side of the Sun as the Voyagers, it’s closer,” Candice Hansen-Koharcheck, a senior scientist at the nonprofit Planetary Science Institute, tells Inverse. “When it [Earth] is on the opposite side of the sun from the Voyagers, that's when they’re further.”

Hansen-Koharcheck said the way to understand best that is to take a piece of paper and draw a dot in the middle representing the Sun. Then draw a line from the Sun to the edge of the paper; that’s one of the Voyagers moving towards interstellar space.

Next, draw a circle around the Sun. That circle represents Earth’s orbit. As the circle shows, there are times in our planet’s 365-day journey around the sun when we happen to be on the opposite side to the exiting Voyagers, producing the greater distance.

Both Voyagers are wandering off toward points beyond the Solar System in different directions.

How long will the Voyager probes last?

Both Hansen-Koharcheck and a representative from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory noted the temporary greater distance between the spacecraft and our planet has no impact on communications or the mission. The Deep Space Network, an array of antennas around the Earth, keeps tabs on the nuclear-powered Voyagers’ communications.

“It doesn't make a lot of difference to the Deep Space Network because Earth is so far away now from the Voyagers,” Hansen-Koharcheck says. While there would be a slight difference in signal strength, both Voyagers have enough power to continue transmitting for now.

The two spacecraft will celebrate 45 years of space operations this summer. This is two to four times the lifespan of a typical solar-powered spacecraft. But this situation won’t continue forever, the JPL representative said.

“Both spacecraft are dealing with dwindling power supplies because their onboard RTGs [radioisotope generators] continue to decay, reducing their power output by about 4 watts per year,” the representative tells Inverse in an email.

“For the last few years, the team has been switching off heaters and other subsystems that aren’t critical to the operation of the spacecraft or the science instruments,” they say. “That has included a few science instrument heaters, but amazingly the instruments continue to operate. The engineering team has really done an incredible job keeping these two spacecraft going.”

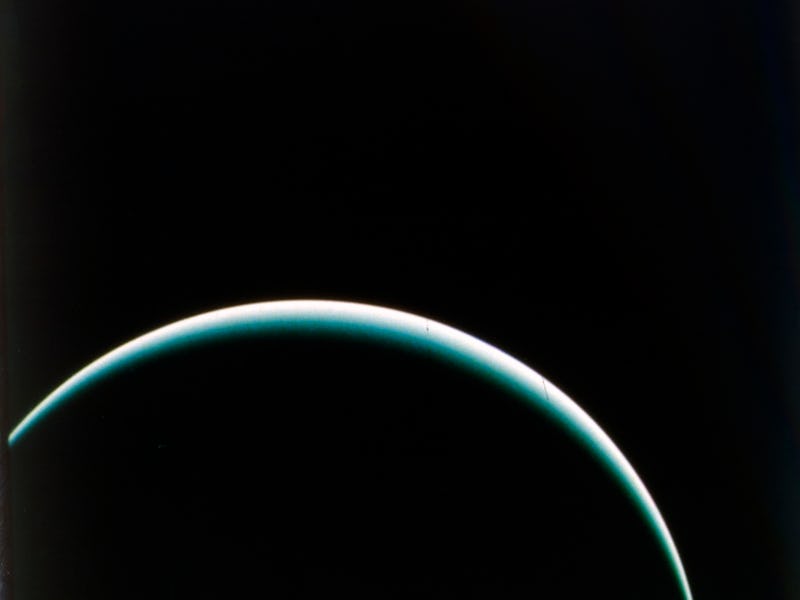

NASA edited this composite to show the view on leaving the area around Triton.

Will NASA ever send a probe to Neptune?

Hansen-Koharcheck and Heidi Hammel, now vice-president for science at the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA), were both on the Neptune imaging team when Voyager 2 made its historic flyby in 1989. (Hammel was unavailable for an interview before this article’s deadline.)

“She [Heidi] was the person who knew the most about Neptune, as seen through a telescope,” Hansen-Koharcheck, who worked at JPL at the time, says of Hammel’s contribution. “So Brad Smith, the head of the imaging team, invited her to come.”

Hansen-Koharcheck’s job was taking care of Voyager 2’s slow-scan color TV camera to take images of the planets, and programming the spacecraft’s imaging observations. She recalled that the spacecraft’s view of Neptune began to improve over ground observations about six or eight months before the spacecraft reached its closest point on Aug. 25, 1989, which meant several intense months of work for the imaging team.

“Every afternoon, Heidi and I had this little appointment, so to speak, where she would walk over from her office. She and I would go into what was essentially a broom closet, but it was basically a place where you had no window. You can look at the screen and pull up the images,” Hansen-Koharcheck says.

“We would pull up the day's data. Heidi kept all the notes, and I operated the computer. The two of us were the first to see things like the Great Dark Spot [storm] and to start measuring its rotation rate from the images … and looking at the different circulation of the different latitudes of the atmosphere,” she adds.

Hansen-Koharcheck says the Neptune encounter and the teamwork of the camera personnel together produced “wonderful times” and says she is hopeful that the community’s decades of lobbying will help produce a new mission to Neptune.

But so far, the deep blue planet hasn’t yet been graced with another attempt. A close shave occurred in 2021 with Trident, a proposed Discovery-class mission from NASA that would have flown by Neptune and its largest moon, Triton in 2038. The agency elected to pass over that finalist mission in favor of two missions to Venus, called DAVINCI+ and VERITAS.

This article was originally published on