Why Venus May Be Our Best Bet For Finding Life In the Solar System

Venus and Earth once looked a lot alike. Could our planet’s forgotten early twin also contain life?

One of the weirdest places in our Solar System may actually be a great place to search for alien life: the skies of Venus.

We don’t have evidence of life — or even indisputable evidence that life could survive — in any world but the one we currently live in. However, recent years have raised the tantalizing prospect that our Solar System, in which we thought we were alone, may be dotted with diverse, and deeply weird, homes for life: In dark water beneath the ice of Europa and Enceladus, in briny underground refugia on Mars, and even drifting in the acidic clouds of Venus.

“If it had liquid water in the past, and if we can really confirm that, then yes – Venus would likely be the planet I would place my bet on,” University of Wisconsin-Madison planetary scientist Sanjay Limaye tells Inverse.

Limaye and his colleagues, along with several other teams of researchers, presented their work in a recent collection of papers in the journal Astrobiology.

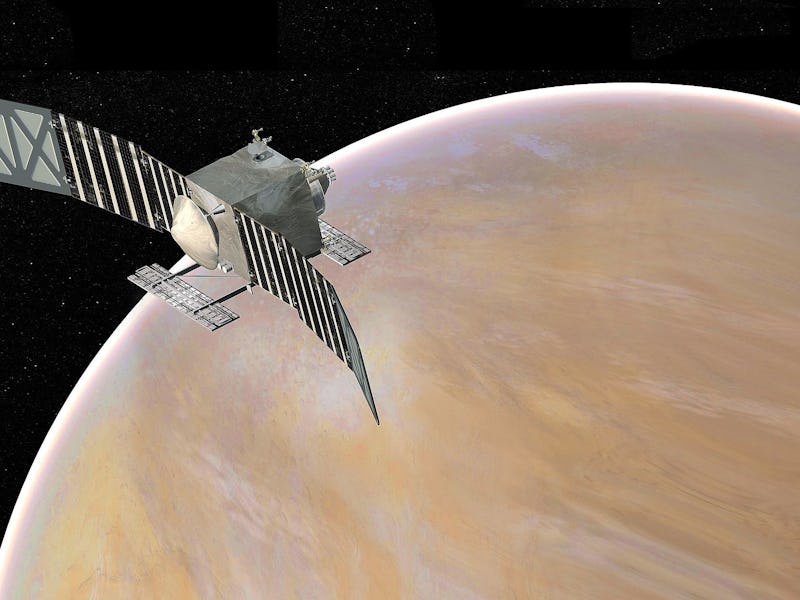

The Japanese Space Agency (JAXA)’s Akatsuki spacecraft captured this infrared view of Venus’s equatorial clouds.

Betting on Venus

In a series of recent papers, several teams of planetary scientists and astrobiologists argue that although the surface of Venus is undeniably an uninhabitable hellscape — you can’t do organic chemistry in a place that’s hot enough to melt lead — the sulfuric acid clouds might actually contain just enough water and other key chemicals for microbes to make a living.

What we know about Venus suggests that there’s something going on in our evil twin planet’s atmosphere that we don’t understand yet, whether it’s alien life or unusual chemical reactions that we’ve never seen anywhere else is still hotly debated.

A few years ago, a team of scientists detected a chemical called phosphine in Venus’s atmosphere. Here on Earth, the chemical reactions that create phosphine only ever happen inside living things, so some astrobiologists immediately got very excited about its presence on Venus. But in a recent paper, chemist Klaudia Mráziková of the Czech Academy of Sciences and her colleagues proposed a way that chemical reactions in the atmosphere could make phosphine without any help from life — and they’re not the first, although co-author Paul Rimmer of Cambridge University tells Inverse that he thinks their scenario is the “best hypothetical abiotic source for phosphine” so far.

Meanwhile, high in Venus’s atmosphere, something is absorbing huge amounts of ultraviolet radiation from the Sun. Over the last century, planetary scientists have suggested several chemical compounds, in different combinations, that could be absorbing the UV light, but no explanation quite fits, at least so far. And in a weirdly compelling coincidence, the shape of whatever’s absorbing the light, and the way it changes with the Venusian seasons, bears a striking resemblance to algal blooms in Earth’s oceans. Like the phosphine, it could be alien microbes busily doing photosynthesis, or it could be fascinating undiscovered chemistry.

And then there are the Mode 3 particles. These weirdly shaped particles in the lower cloud layers of Venus are less than a ten-thousandth of an inch wide, but that’s surprisingly large for particles floating in clouds. The Pioneer Venus mission discovered them in early 1971, when one of its instruments measured the tiny shadows of particles passing by. They’re not tiny spheres, but amorphous blobs, and some scientists wonder whether they might be cells living in the droplets of liquid that make up the clouds.

As incredible a discovery as that would be, the Mode 3 particles could also be an optical illusion; the result of overlapping shadows of round droplets, or a problem with the Pioneer Venus instrument’s calibration. They could also be grains of dust blown aloft from the dead surface of Venus, or something else entirely.

All of these mysteries could be clues pointing to alien life in the Venusian clouds – or they could be a stack of coincidences, which future astrobiologists will one day use as a cautionary tale. We just don’t know yet.

“There are far more unanswered questions about Venus than any other planet,” says Limaye.

A Tale of Two Planets

Venus is both the most and the least Earth-like planet we know of. It’s about the same size as our home world, and it’s also a rocky world, shrouded by an atmosphere, in the habitable zone of our Sun. But Venus is also a hellworld that rotates backwards, where temperatures on the ground could melt lead and the clouds rain sulfuric acid. But some scientists argue high above the deadly heat and crushing pressure of the surface, the acidic clouds actually aren’t so bad, that is if you’re a microbe evolved to like that sort of thing.

“Venus is often overlooked as a target for astrobiology,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology astrobiologist Janusz Petkowski tells Inverse. “This is an unfair assessment.” Petkowski and his colleagues recently published a paper in the journal Astrobiology presenting a case for a habitable niche in Venus’s clouds.

Once upon a time (almost 4 billion years ago, that is), the young planets Venus and Earth probably looked a lot alike. The fledgling Venus may even have had seas of liquid water, much like the environments where life probably emerged from chemistry on Earth. Researchers like Petkowski and Limaye argue that if Venus and Earth were similar during their youth, there’s no reason life couldn’t have emerged on Venus just like it did on Earth (it’s also plausible that the same thing was happening on Mars at around the same time).

But, as siblings sometimes do, the two planets took very different paths in their adolescent years. For various reasons, Venus’s atmosphere acted like a greenhouse, holding in heat until the seas boiled away and the clouds turned noxious and acidic. But that process took at least a hundred million years, and Petkowski, Limaye, and others are betting that some Venusian life may have evolved quickly enough to survive as the seas evaporated and the clouds got more and more acidic. If they’re right, then colonies of microbes could still be drifting in the upper layers of Venus’s atmosphere, where temperatures are more hospitable, clinging to droplets of fluid or tiny grains of dust that make up the clouds.

This elevation map, made by the Magellan spacecraft’s radar, shows what lies beneath the clouds of Venus.

Life, Uh, Finds a Way

“No life on Earth could actually survive in Venus’s clouds,” says Petkowski.” “But if we define habitability as an environment that allows any kind of organic chemistry to survive – maybe even life with different chemical composition and different biochemical solutions – then Venus’s clouds could be potentially habitable.”

The cloud layers of Venus’s upper atmosphere stay between freezing and boiling — exactly the right temperature range for life — but they’re made mostly of droplets of sulfuric acid, mingled with a few microscopically tiny droplets of water. No environment on Earth is remotely similar. But seeing how the scrappiest, stubbornest Earth life has adapted to milder versions of these challenges, astrobiologists can learn how life might adapt to the harsh conditions of Venus.

Here on Earth, for example, some microbes that live in acidic hot springs have found ways to neutralize the acid around them. Venus’s clouds are much more acidic than even the most caustic hot springs here on Earth, but given millions of years to adapt, it’s possible that microbes could keep pace with their changing environment. Petkowski and his colleagues suggest that multi-layered cell walls or acid-resistant membranes could also help microbes keep the acid out and the water in.

For now, that’s all speculation, but in recent lab experiments, Worcester Polytechnic Institute chemist Maxwell Seager and his colleagues found that some amino acids (chemical compounds that form the building blocks for proteins) are completely fine hanging out in a mixture of 98 percent sulfuric acid and 2 percent water. In previous experiments, the same team learned that nucleic acids (the molecules that store the genetic code) are also undaunted by super-acidic conditions.

That could be good news for life, but surviving the acid clouds is just one part of the challenge. Life — at least life as we know it — needs water to survive, and if there’s water in Venus’s clouds, it exists in the form of microscopic droplets, and even those are probably few and far between. In the driest places on Earth — carefully climate-controlled libraries — some resourceful microbes use nearby salt to pull just a few molecules of water out of the air. It’s not hard to imagine microbes on Venus doing something similar while clinging to a droplet of liquid in a cloud.

But could microbes spend their whole lives in the air? Some microbes here on Earth spend part of their life cycle in the clouds, but on Venus, sinking too deep into the haze below means a boiling death. Petkowski and colleagues say that resourceful microbes could lock themselves into armored balls called spores when their environments get too hot; inside the spore, a dormant microbe could wait until wind currents lift them back up to where things are cooler.

In other words, life finds a way. Or at least, it theoretically could. We need a lot more information to know for sure, or even to say how likely this scenario could be.

This artist’s illustration shows what the DAVINCI probe might look like as it falls through Venus’s atmosphere.

Will we ever find a smoking gun?

Upcoming missions to Venus may help answer some questions about what’s really going on in the sulfuric acid clouds: How much water is there? Are there organic molecules? Did Venus ever have liquid water on its surface? All of these are pieces of a much larger question: Could the clouds of Venus be habitable, even for a kind of life that we’ve never seen on Earth?

A commercial spaceflight company called Rocket Lab plans to launch its Venus Life Finder mission in December 2024. Venus Life Finder will look for organic molecules in the upper cloud layers. Finding these molecules won’t prove there’s life on Venus (despite the mission’s ambitious name), but it would show that the acidic clouds are home to the kind of chemistry that makes life work. This would be an encouraging sign.

NASA’s DAVINCI mission, which is planned for a 2029 launch, will study Venus’s atmosphere from orbit — and drop a probe into it. A couple of years later, in 2031, NASA’s VERITAS mission will study the planet’s surface and it’s interior. At around the same time, the European Space Agency’s EnVision mission will also use radar to study the interior of Venus from space.

All of these missions could help scientists understand whether Venus ever had liquid water on its surface, and how the planet’s atmosphere evolved over time (ratios of different chemical isotopes in a planet’s atmosphere can contain clues about its history). They may also help find explanations for the phosphine and even the mysterious UV absorber.

However, all of these missions are still years away even if everything goes according to plan. As JWST and Artemis have both shown us, it seldom does; they call it rocket science for a reason. And none of them will be capable of actually detecting life among the clouds of Venus , only clues about whether it could survive there. The only way to find real proof of life on Venus, according to researchers like Petkowski and Limaye, will be to scoop up a sample of the Venusian clouds and bring it home.

And that possibility is still decades away.

“It will take at least a couple of decades or longer, given the rate at which the previously selected missions are taking to actually be implemented,” says Limaye. “It will be a long time before we actually detect life elsewhere. It's not going to be a single experiment. It's going to take a lot of effort and different experiments and investigations and missions to determine.”

In the meantime, we can speculate, and scientists can find new ways to analyze the data they have. And we can all enjoy the possibility that our Solar System may be a lot wilder and a lot livelier than we thought.