Scientists want to map the genome of a slime-shooting worm — here's why

The velvet worm is a slime-shooting carnivore straight out of Pokémon.

A peculiar predator skulks across the forest floor.

It’s dreadfully slow, but the cover of darkness — and leaf litter — keeps it hidden. It glides along dozens of stumpy legs, but it’s no centipede: It’s a velvet worm, and it’s hunting for its next meal.

Unable to see in the dark, the velvet worm feels its way with its two antennae, sensitive appendages that evolved from legs hundreds of millions of years ago. Some say it can even pick up on tiny movements of air that alert it to the presence of nearby prey.

Detecting a snack — or perhaps startled by an enemy — it engages an ancient attack that puts Spiderman’s web fluid to shame. Using dual super-soakers mounted on either side of its face, the velvet worm shoots a gooey liquid scientists refer to as “slime” that coats its foe and hardens instantly, rendering them motionless so the worm can chow down at its own pace.

But the velvet worm is more than great Attenborough fodder — or the inspiration for the next generation of Pokémon. It’s of significant evolutionary interest.

According to Shoyo Sato, a graduate researcher at Harvard University who’s currently assembling the first velvet worm genome, this creature could solve an ancient genetic mystery.

That’s no silly string

A Malaysian velvet worm.

The slime of the velvet worm is unique. Unrelated to the sticky silk of spiders and insects, its molecular structure is such that as water evaporates from it, it hardens and gets steadily stickier. Researchers call this a “glass transition change resulting in adhesive and enmeshing,” which is, scientifically speaking, incredibly dope. The more prey struggle, the faster the slime hardens.

Even their sexual behavior is weird. (Don’t worry, it doesn’t involve slime.) Some velvet worms lay eggs, as you might expect, but others give live birth, placenta and all. In some species, the males’ sperm-containing organ is on their head, which he uses to transfer a sperm packet to the female’s genital opening.

In other species, the male just deposits a sperm packet anywhere onto the skin of the female. It dissolves the skin underneath and the sperm get inside, finding their way to the eggs in the body.

“Yeah, it’s sort of gross,” says Sato. “But also a really fascinating method of insemination.”

Biologist’s bounty

“There’s nothing else like them.”

The velvet worm’s unique traits and lineage make it a great tool for studying evolution. Velvet worms form a unique phyla called Onychophora. This means that they’re as unique from other animals as mammals, starfish, tardigrades, and clams all are from each other.

“There’s nothing else like them,” says Sato. “They’re a completely unique lineage of animal.”

Sato’s got a big task ahead assembling the first velvet worm genome. It’s an important first step toward knowing which genes they have, what they do, and where they are among all their DNA. This info will allow scientists to learn more not just about how velvet worms work and their evolutionary history, but also about animal evolution in general.

But the velvet worm genome is large, with contains about twice the amount of DNA as humans. It also contains a lot of what’s called repetitive sequences — repeated regions that make it extra challenging to figure out which order the genes are in. This makes the process a bit like putting together a puzzle with a lot of pieces that are nearly the same shape and color.

Velvet worms are considered a sister group to the Arthropods, by far the most diverse group on the planet with literally millions of species of insects, arachnids, and crustaceans. Studying the similarities and differences between the groups can reveal which adaptations came from long-ago ancestors and which came along more recently. This can, in turn, give clues about what allowed the Arthropods to diversify so much.

Meanwhile, there are only about 200 different Onychophora, and they’re the only phylum in the world that only includes terrestrial species. All others have at least some marine representatives, Sato explains. Yet another mystery genetic coding can solve?

Making of a mini-monster

3D rendering of the Hallucigenia, a prehistoric aquatic animal from the Cambrian Period.

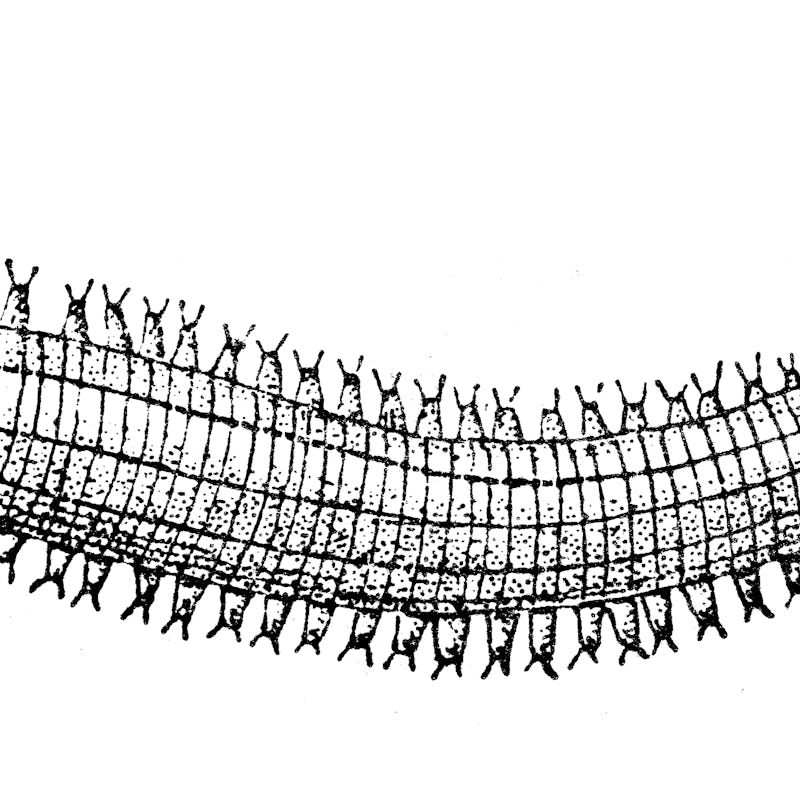

Even within just those 200 species, the velvet worms have a cool evolutionary history. The glands that house their slime run along the entire length of their body, and evolved from excretory glands called nephridia that filter waste for invertebrates (like kidneys).

The super-soakers on their face are called oral papillae, and they evolved from legs. Ditto their antennae — which, interestingly, are different from insect antennae. They come out of the first segment of velvet worms’ heads, as opposed to insects and other arthropods, which come out of the second segment. It may not sound like a big difference, but it means a lot for how they develop and, likely, how they evolved.

A lot of their traits are old, evolutionarily speaking. And by old, we mean really old — they can be traced to the Cambrian period 500 million years ago. That’s older than birds (150 million), trees (350 million), and even sharks (450 million).

There are even fossils in the Burgess Shale, a big 508-million-year-old fossil deposit in Canada, that are thought to be not-so-distant ancestors of the worms. Namely, Hallucigenia, an ancient animal with too many legs and spines for its own good. (OK, it’s not that many. More like 20 legs and 14 spines.)

On a molecular level, evolution doesn’t stop. So the fact that these critters have remained outwardly similar for hundreds of millions of years is peculiar — it’s rare across biology and is a mystery worth solving.

In a Pokémon world...

Caterpie in the Pokémon franchise.

Although they’re neither true bugs nor even arthropods, velvet worms are certainly bug types, with a mean string shot that reduces their opponent’s speed. Their attack is super effective, but their defense is lacking: They’re slow, squishy, and very susceptible to drying out. Match them with a small enough opponent in an arena where they can stay moist, and they’ll surely unleash their attack, rendering any enemy motionless so they can move in for the slow-motion kill.

But humans need not worry. “They’re not dangerous,” says Sato. “They’re slow. They don’t bite or anything. You might get slimed, though.”

Velvet Worm stats

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Onychophora

- Habitat: forests

- Legs: 13 to 43 pairs

- Range: Caribbean, Central America, South America, Southeast Asia, West, and South Africa, Oceania

- Size: less than a centimeter, to over 20 cm

- Number of species: ~200

- Prey: termites, small invertebrates

- Special abilities: Adhesive slime

This article was originally published on