Scientists Drilled Into An Underwater Mountain In the Atlantic’s ‘Lost City’ To Obtain A Massive Core Sample

The deep ocean is packed with clues about early life.

There’s a special kitchen at the bottom of the sea. Scientists are now closer to reconstructing how it whipped up early life, thanks to a massive 1.2-kilometer core that a ship drilled out from a Mount-Rainier-sized underwater mountain in the Atlantic Ocean.

Johan Lissenberg, igneous petrologist at Cardiff University, and his colleagues are fascinated with the extreme temperatures of melted rock. Earth churns out molten rock, and seawater cools it down. It is intrinsic to the planet itself, and likely created life. The undersea mountain, called the Atlantis Massif, is home to a hot spring environment known as the Lost City hydrothermal field. Eons ago, a place like this may have been the cradle of unique microbes and the creatures that consumed them.

In a new study published Thursday in the journal Science, Lissenberg and a team of scientists analyzed the mantle rock the JOIDES Resolution research ship drilled out of Atlantis Massif last year. The trip was led by the International Ocean Discovery Program.

The remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Hercules approaches a ghostly, white, carbonate spire about 2,500 feet below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean, in the Lost City hydrothermal field of Atlantis Massif.

Down below the surface

Atlantis Massif is one of the rare places on Earth where geochemists can get their hands on material from the largest part of our planet: the upper mantle.

“Say three to four billion years ago, the continental crust was formed from magma that was sourced in the mantle," Lissenberg tells Inverse.

“But the oceanic crust is always forming. Every day, basically,” he adds. As subaquatic tectonic plates spread apart, the melted rock that makes up Earth's mantle rises up. The material that reaches the surface forms new crust. So, the drill core is a snapshot of processes happening deep below the oceanic floor otherwise inaccessible to researchers.

“The rocks that were present on early Earth bear a closer resemblance to those we retrieved during this expedition than the more common rocks that make up our continents today,” Susan Lang, an associate scientist in Geology and Geophysics at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and co-chief scientist on the expedition, said in a study announcement.

Enigmatic reactions

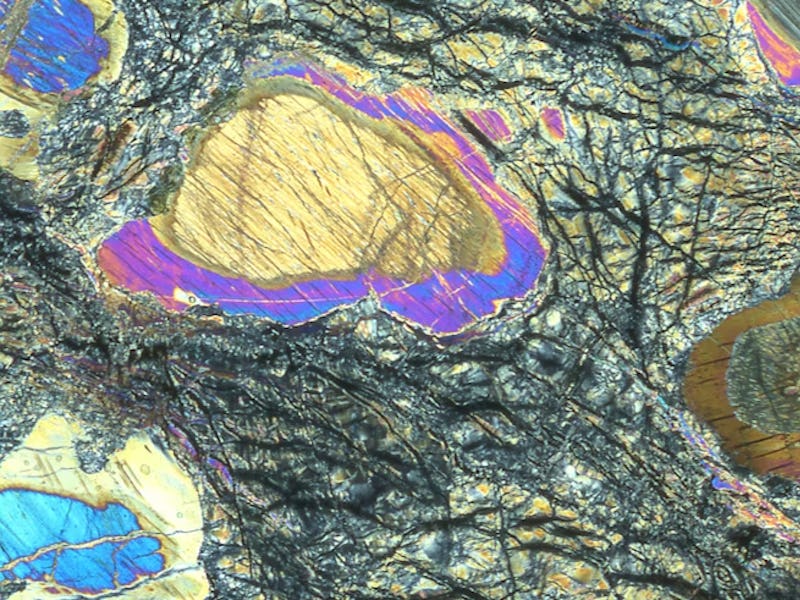

The ship’s sample is mantle rock, the residue of partial melting underneath Earth’s crust. Embedded within it are minerals that may have been key to understanding early life, like serpentine. This mineral gets its name from a resemblance to snake skin. It’s usually grayish, white or green in color. It occurs when the primary mineral in mantle rock, called olivine, reacts with seawater.

This process releases hydrogen. “Hydrogen can then make compounds such as methane, which can then underpin microbial communities,” Lissenberg says.

Going forward, Lissenberg really wants to understand those reactions. The new study is a start. As the team logged the details of the core centimeter by centimeter, they were surprised. Instead of being rather homogenous, they saw a variability in the mineral composition.

This matters when scientists reconstruct the “chemical kitchen,” Lissenberg says, that led to reactions supporting life. Ultimately, Lissenberg wants to understand all the “flavors” of the upper mantle.