This ancient fish with arms might be the reason you have hands

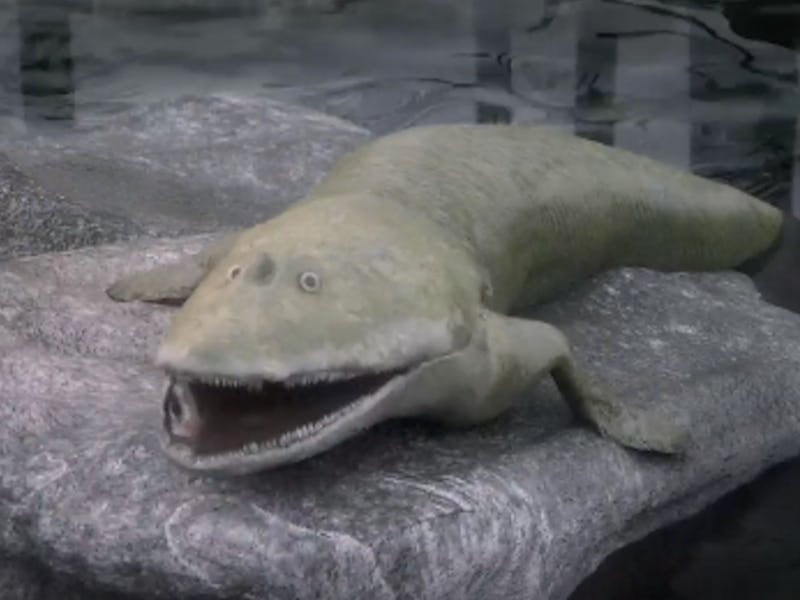

"A crocodile-like body shape with a flat triangular head, numerous teeth around the jaws and in the palate..."

Scientists have long believed the human hand evolved from an ancient, four-limbed creature, but this creepy fossil finding begs to differ.

The discovery of an ancient fish fossil in Canada reveals how the human hand may have actually evolved from a meter-long fish with arm-like fins that lived some 380 million years ago.

Using high energy CT-scans to analyze a fossil found in 2010 in Canada, paleontologists discovered the fish’s fins had the same bones a human arm and hand.

The finding provides paleontologists with conclusive evidence of the missing evolutionary link in the development of the human hand.

The discovery is detailed in a study published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

Fish fingers

The ancient Elpistostege watsoni fish was a large marine predator from the Late Devonian period, about 393-359 million years ago. The fanged, 1.57-meter-long marine animal stands out among the other large fish of the time, the researchers say.

“Personally, I think Elpistostege is one of the most beautiful creatures that lived on Earth. Seriously, it is a great tetrapod-like fish or fish-like tetrapod,” Richard Cloutier, a professor at the Quebec Centre for Biodiversity Science, tells Inverse.

“Elpistostege provides further information on our own body plan, ‘our inner fish.’”

Elpistostege was primarily an aquatic animal, with a crocodile-like body covered in thick scales, and a flat, triangular head, eyes on the top of the skull, numerous teeth around the jaws and in the palate, and well-developed, paired fins, according to Cloutier.

To get a sense of what that looks like, Cloutier and his colleagues made this animation to show you:

"The three of us [researchers] worked closely together to produce an illustration that was the most accurate based on the exceptional fossil that was found. The anatomical details are truthful, but obviously we have no direct indication about the real-life color," Cloutier says.

Previously, paleontologists described the Elpistostege as a really advanced, lobe-finned fish. And, as you can see in the video above, the Elpistostege was among the first creatures who made the leap from shallow water to land.

“On the continent near the estuaries and rivers, the first forests of 10-meter-high, tree-like ferns were growing,” Cloutier says.

“On land there was no vertebrate, only different types of invertebrates such as scorpions and millipedes. In the shallow estuary, Elpistostege was swimming with some 20 different species of fishes.”

As it developed to lurk and feed on land and in water, the fish evolved limbs that could support its desires and needs. So well-developed are these limbs, the researchers reveal, that the Elpistostege fish had a pectoral fin with the complete arm skeleton composition.

That's a humerus, radius and ulna, a row of carpus (which make the wrist), and all the phalanges organized like fingers.

Comparison of the anatomy of the pectoral limb endoskeleton (a) and humerus (b) of stem-tetrapod fish

Yep. That’s a fish with arms and fingers.

“Using a high energy CT-scan, a state-of-the-art technology, we managed to virtually visualize within the complete fossil and more specifically within the pectoral fin,” Cloutier says. This marks the first time paleontologists have discovered unequivocal evidence of fingers locked in a fin in any known fish.

These finger-like digits were necessary for the fish to support its weight and develop some sort of flexibility as it trod on land during short hunting trips out the water. That is also the reason it developed an arm bone structure similar to amphibians.

Based on these wild findings, the researchers suggest that the vertebrate hand — ie, our hand — "arose primarily from a skeletal pattern buried within the fairly typical aquatic pectoral fin of elpistostegalians."

Fishy evolution

The moment when fish developed into tetrapods (four-legged vertebrates like lizards but also like humans) was one of the most important moments in the history of evolution. That’s when vertebrates started to leave the water and take over land, an evolutionary transition that led to the development of hands and feet as we know them.

With these findings, researchers can now track the evolution of the hand beyond ancient four-legged animals, to the level of a fish.

"All of the digitate tetrapods share the same basic pattern found in Elpistostege."

Now, this does not necessarily mean the Elpistostege is our direct ancestor, but it is one of the few transitional fossils we know of to showcase a moment in our own evolutionary development.

“Limbs, hands and digits are the most vital anatomical structures for the evolution and diversification of tetrapods, whether it is to walk, to swim, to fly, to dig, to grab … these structures have a crucial functional significance,” Cloutier says.

Complete specimen in dorsal view.

“More than 30 000 species of living tetrapods have various types of digits or fingers. It could vary in number, in length, in terms of the number of phalanges per digit, etc. But all of the digitate tetrapods share the same basic pattern found in Elpistostege.”

The discovery is also significant because the fossil is so well-preserved, Cloutier says.

“Until recently, only three extremely incomplete fossils of Elpistostege had been found at the exceptional UNESCO World Heritage Site of the ‘Parc national de Miguasha’,” Cloutier tells Inverse.

But this fossil of Elpistostege, found in the Miguasha cliffs along the Gaspé Peninsula in eastern Quebec, completely changes the game. To the researchers’ knowledge, this is the sole elpistostegalian animal for which scientists have complete knowledge of body shape and proportions.

The Elpistostege will likely become a textbook example to talk about the origin of tetrapods as well as the origin of hand," Cloutier says.

“Elpistostege provides further information on our own body plan, ‘our inner fish.’”

Abstract: The evolution of fishes to tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates) was one of the most important transformations in vertebrate evolution. Hypotheses of tetrapod origins rely heavily on the anatomy of a few tetrapod-like fish fossils from the Middle and Late Devonian period (393–359 million years ago)1. These taxa—known as elpistostegalians—include Panderichthys2 , Elpistostege3,4 and Tiktaalik1,5 , none of which has yet revealed the complete skeletal anatomy of the pectoral fin. Here we report a 1.57-metre-long articulated specimen of Elpistostege watsoni from the Upper Devonian period of Canada, which represents—to our knowledge—the most complete elpistostegalian yet found. High-energy computed tomography reveals that the skeleton of the pectoral fin has four proximodistal rows of radials (two of which include branched carpals) as well as two distal rows that are organized as digits and putative digits. Despite this skeletal pattern (which represents the most tetrapod-like arrangement of bones found in a pectoral fin to date), the fin retains lepidotrichia (fin rays) distal to the radials. We suggest that the vertebrate hand arose primarily from a skeletal pattern buried within the fairly typical aquatic pectoral fin of elpistostegalians. Elpistostege is potentially the sister taxon of all other tetrapods, and its appendages further blur the line between fish and land vertebrates.