NASA gets its planet-hunting telescope back online after glitch

NASA's extra-solar planet hunter is pausing observations.

NASA’s primary planet-hunting spacecraft paused its search for alien worlds two days after its most-recent data downlink. But some good news is on the horizon.

On October 10, NASA’s TESS mission entered safe mode. While the telescope was believed to be stable, according to the space agency’s October 12 announcement, it meant that science observations were suspended. NASA said recovery procedures were underway, but “could take several days.”

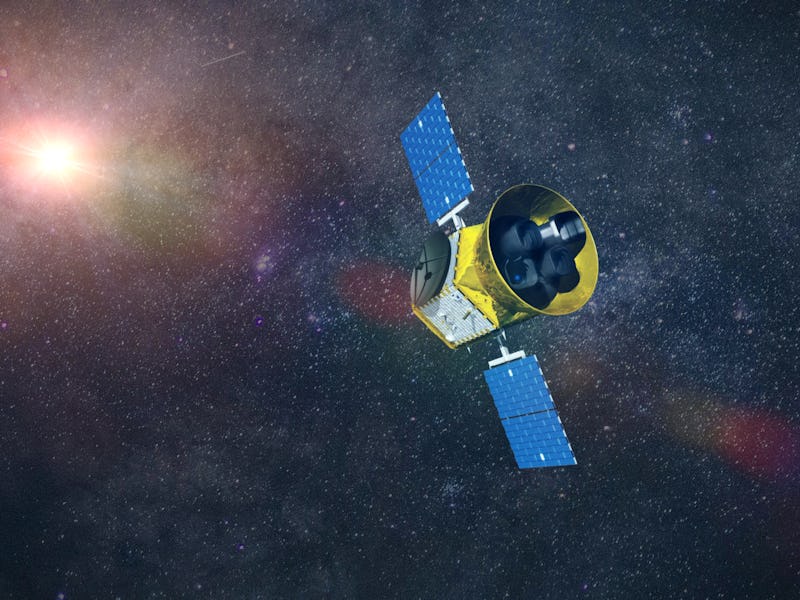

TESS’ full name — Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite — outlines how it has operated to detect more than 250 exoplanets (and thousands of candidates) so far. As the four-year-old mission surveys stars, it watches for dips in brightness. If these blinks happen periodically, it’s a sign that a planet orbits a star and eclipses some of its light from Earth’s perspective when it passes in front.

This work was paused. Fortunately, NASA announced a positive development days later.

Note: This article was updated twice. First, on Friday, October 14, with new information from Knicole Colón, TESS project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Then again on Tuesday, October 18, with NASA’s new status update.

“Preliminary investigation revealed that the TESS flight computer experienced a reset,” adds the space agency. According to Colón, this means that “some automated tasks that run on the flight computer got stuck, forcing the computer to reset itself to its original state.” The cause of this was under investigation, and thankfully, TESS “began its return to normal operations” on Thursday (October 13) around 6:30 p.m. Eastern, the space agency announced on Friday (October 14).

TESS successfully sent data back to Earth on Saturday, October 8, according to Knicole Colón, TESS project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Colón is an exoplanet astrophysicist, and announced the first infrared spectra of an exoplanet by the James Webb Space Telescope in July 2022.

“There is approximately two days of data stored on the spacecraft waiting to be downlinked,” Colón told Inverse. “TESS normally downlinks data approximately on a weekly basis.” Fortunately, the data appeared to be safely stored, according to NASA’s statement.

To get TESS running again, the team also had to monitor the temperatures of the cameras. “Once they are at nominal operating temperatures,” Colón said, “then science operations are anticipated to resume.”

On Friday, engineers successfully powered up TESS, “and the spacecraft resumed its regular fine-pointing mode,” said NASA.

Why exoplanets matter

Exoplanet science has come a long way since 1995, when Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz made the first discovery of a planet orbiting a Sun-like star. This celestial body, called 51 Pegasi b, is unlike anything found in the Solar System. Its strange attributes include a gaseous mass roughly half of Jupiter and a tight orbit of just 4.2 days around its parent star. MAyor and Queloz would later go on to win the Nobel Prize in Physics for their work.

The oddity of early exoplanet discoveries like 51 Pegasi b highlighted the importance of researching these faraway worlds.

TESS inherited the task of NASA’s Kepler spacecraft, which launched in March 2009 to survey a portion of the Milky Way galaxy. During its primary mission, and later an extension called K2, Kepler collected data that confirmed the existence of 2,600 exoplanets. It also indicated that the night sky is filled with “billions of hidden planets.”

TESS launched in April 2018 to observe an area of sky 400 times larger than what Kepler monitored. As TESS identified new exoplanets, astronomers could categorize them, learn about star-planet relationships different from the Solar System and make predictions about how planets evolve.

This article was originally published on