The Sun's Absurdly Hot "Crown" Holds One of the Biggest Mysteries in Astronomy

The corona is a "natural laboratory" that cannot be replicated on Earth.

Valery Nakariakov, a physicist at the University of Warwick in England, studies the hottest part of our Sun. Mathematically speaking, he says, our home star is like a musical instrument, a grandfather clock, or even a human heart. That’s according to his most recent work, published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

When something flows, Nakariakov tells Inverse, like a pendulum swinging, music playing, or blood pulsing through our veins, it must take its energy from somewhere. The same principle, he surmises, applies to the Sun as it generates kink oscillations, a phenomenon that seems to be driven by energy within the star.

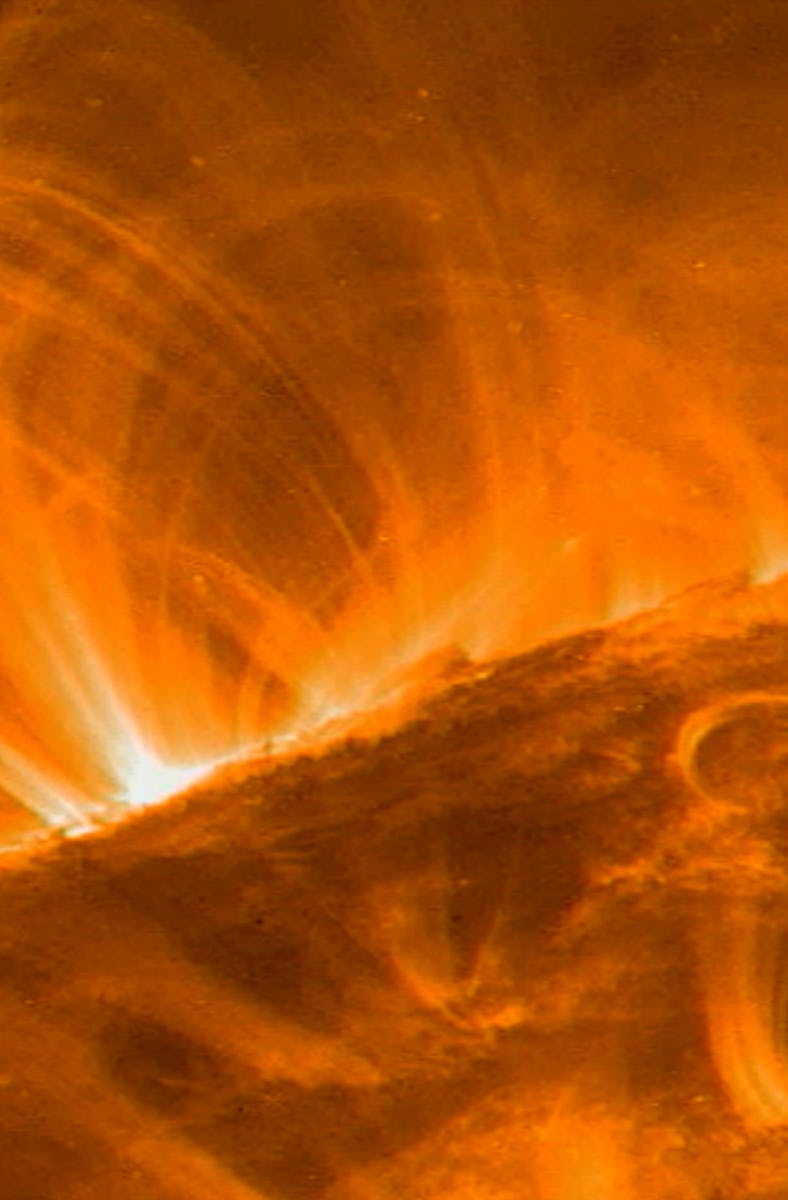

The oscillations are found within loops in the Sun’s corona, the outermost shell of the Sun’s atmosphere. It’s also the hottest part of the star and makes up the halo skygazers see during total solar eclipses.

The sun's coronal loops are shown in this photo, released September 26, 2000, taken by special instruments on board NASA's Transition Region and Coronal Explorer (TRACE) spacecraft.

Why study the Sun’s corona?

The corona is the outermost shell of the Sun’s atmosphere, and it is made up mostly of hot gas-like plasma. It is a “natural laboratory” that cannot be replicated on Earth, says Nakariakov.

It gives the closest look that astronomers can get to what happens around other stars and exoplanets around them.

Closer to home, the solar wind’s plasma does a lot for our cosmic neighborhood. Astronomers think the corona is the source of the sea of charged particles, known as the solar wind, that bathe the Solar System. It keeps cosmic rays from beyond our frontiers at bay, changes cloud coverage on Neptune, lights up auroral displays on Earth, can disrupt satellites, and even initiate blackouts. The solar wind is one of the biggest topics in modern astronomy.

A peculiar world of plasma

Nakariakov is zeroing in on a subfield of Sun science called magnetohydrodynamic wave phenomena within the corona’s plasma. We’re most familiar with the solid, liquid, and gas states of matter, but most of the universe is actually plasma, a step beyond gas, where atoms are split into ions and electrons.

As NASA explains, plasma is capable of some weird fluid dynamics, and it also has electromagnetic activity because of the charged particles. Altogether, places ripe with plasma are home to material oscillating in ways that feel unnatural to us on Earth.

And solar physicists like Nakariakov want to know more about them.

When his team looked at data from the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) instrument onboard NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory and the Extreme-Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) on the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter, they saw something unexpected. Nakariakov describes their strange finding, found in a solar process called kink oscillations, as “just like the oscillations on, say, like a guitar string.”

The total solar eclipse of August 21, 2017 over Oregon.

Is the Sun like a guitar or a violin?

Like a string being plucked, the Sun has these motions in its loops in the corona. Astronomers looked for how long it took to decay in that motion. During most oscillations on Earth, like a played guitar string, the sound will eventually cease. But there is no visible decrease in the coronal loop oscillations, suggesting that there should be a mechanism that supplies the energy to sustain the waves.

“We have these oscillations, which are decayless. Meaning they are driven continuously. As this phenomenon is very common, similar mechanisms, which reinforce the energy to those oscillations, would be almost everywhere in the corona,” Nakariakov says.

They saw oscillations from two different positions. The NASA spacecraft orbits Earth, and the Solar Orbiter goes around the Sun. Their instruments suggest to Nakariakov and the team that the energy driving the decayless oscillations wasn’t something random. There is some intrinsic stellar mechanism. It could drive these continuous oscillations, and more importantly, it might also be the source of the corona’s mysterious heating, one of solar science’s biggest questions.

Loop oscillations and coronal heating are two different phenomena, “disconnected from each other,” Nakariakov says. “But the energy supply mechanism might be the same.”

Nakariakov says that the Sun is, therefore, less like a guitar and perhaps more like a violin. It can be plucked, but if a bow moves across the strings steadily and slowly, he explains, the energy is converted into waves.

Scientists will continue to listen to the Sun’s dramatic hums to learn more about our corner of the cosmos and the stars shining far away.

This article was originally published on