Study reveals some jellyfish can launch deadly "mucus grenades"

"A really novel and interesting strategy.”

Have you ever peacefully gone for a swim in calm, warm, shallow waters… and been stung by a jellyfish without even seeing it? Now, researchers may have finally solved the mystery — and revealed yet another reason to fear (and admire) these creatures.

The Cassiopea jellyfish (aka the upside-down jellyfish) have the ability to release toxin-filled "mucus grenades" into the water, stinging unsuspecting humans and prey without actually having to touch them.

In a study published Thursday in the journal Nature Communications Biology, researchers detail the discovery of these grenades, or cassiomes — gyrating balls of stinging cells released within nets of mucus surrounding the jellyfish.

“This is a novel stinging strategy for this jellyfish, which does not really swim up in the water, is using in order to sting things without it having to be touched,” Anna-Marie Klompen, a graduate student at the University of Kansas and author on the study, tells Inverse.

“I think it is, for all jellyfish, a really novel and interesting strategy.”

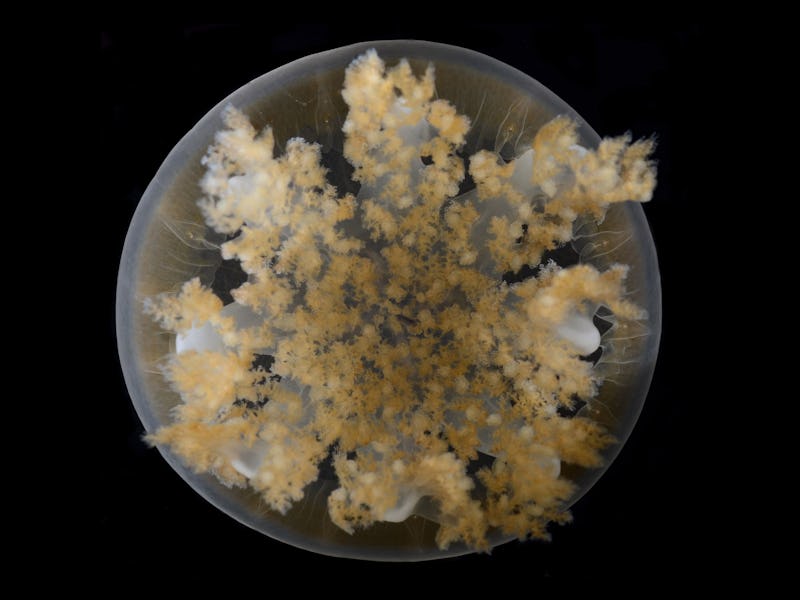

The upside-down jellyfish lie on the bottom of the water

The results may solve mystery jellyfish stings, which can happen when swimmers get stung without seeing or feeling any marine creatures around them — a horrifyingly common occurrence. Jellyfish sting an estimated 150 million people every year.

They also clear up a conundrum about Cassiopea jellyfish. For 200 years, the jellyfish have been studied extensively, but until now, no one knew what these lethal balls of snot were — or what havoc they wreaked. Prior research had even dismissed the possibilities of these stinging cells being part of the jellyfish.

“Mucus is not generally something people look at in jellyfish,” Klompen says. “This is an incredible and weird piece of natural history that we were able to use all these new modern science tools to answer.”

In fact, Cassiopea are thought to have a mild sting, and can be found in lagoons and mangrove forests characterized by sheltered, shallow water. They like to camouflage with the underwater foliage, resting on the seafloor upside-down.

But these strange creatures are not so innocent. Now, we know that Cassiopea also release clouds of sting-laden mucus — like fishers’ nets attached to their bodies — to subdue prey and predators without having to move an inch.

Within the mucus, they release hollow spheres of cells coated in hairlike filaments and stingers. The filaments help these venomous balls travel, while the stinging cells, known as nematocysts, annihilate the target with venom. The mucus bomb shoots no higher than a foot above the jellyfish. After it has done its deadly work, it brings nutrients back to the main body so they can be fed into the animal's pores.

The study shows — in cinematic detail, that cassiosomes are capable of killing brine shrimp in a short amount of time. Watch it for yourself:

Cheryl Ames, associate professor at Tohoku University and lead researcher on this study, re-enacted the bomb effect for Inverse — from the jellyfish's point of view:

“We're down here, we like to be lazy on the bottom, flipping upside down and rather than tentacles and a central oral feeding tube, we have these frilly bits that for all intents and purposes look like the rest of our surroundings. We have these photosynthetic algae within us, but not only have we evolved the ability to like not have to really go to the fridge to get our own food, on a kind of a murky water day or several days of rain where we don't see the sun, when we need something else, why don't we just produce this net that we can cast and keep nutrients handy until we kind of need them.”

“The first day when we put the mucus of the jellyfish under the microscope: it was like a wow moment,” Ames says. “It was like, okay everyone, are you seeing what I'm seeing? Yes. Do you have any clue? No.”

“It's a pretty amazing evolutionary novelty for something with a history of over 600 million years," she says. "It's really opened up a totally new field of research, presenting many opportunities for further investigation."

Ames and Klompen have identified cassiosomes in four more jellyfish species, suggesting there may be even more of these grenade-launching hell creatures out there.

The Cassipea usually hide between marine foliage and blend in because of their colors

These strange jellyfish abilities are yet another example of how underrated and brilliant jellyfish are as creatures, Jason Hall-Spencer, a marine biologist from University of Plymouth, tells Inverse. Hall-Spencer was not involved in the study.

“They are pretty innocent organisms, unless you are the size of a grain of rice,” Hall-Spencer says. "But they are certainly highly evolved to survive, capture prey and get what they need from the Marine ecosystems."

“They are very tough organisms,” Hall-Spencer says.

Jellyfish have survived several mass extinctions — including when the giant meteorites wiped out the dinosaurs.

“Probably some of the groups will survive no matter what we throw at the oceans,” he says.

“Unfortunately, it's been coined, ‘descent to slime' — a situation whereby the big fish and the beautiful organisms in the ocean are getting removed by human activities," he says. That means jellyfish will be left behind. At least they will be well-armed.

Abstract: Snorkelers in mangrove forest waters inhabited by the upside-down jellyfish Cassiopea xamachana report discomfort due to a sensation known as stinging water, the cause of which is unknown. Using a combination of histology, microscopy, microfluidics, videography, molecular biology, and mass spectrometry-based proteomics, we describe C. xamachana stinging-cell structures that we term cassiosomes. These structures are released within C. xamachana mucus and are capable of killing prey. Cassiosomes consist of an outer epithelial layer mainly composed of nematocytes surrounding a core filled by endosymbiotic dinoflagellates hosted within amoebocytes and presumptive mesoglea. Furthermore, we report cassiosome structures in four additional jellyfish species in the same taxonomic group as C. xamachana (Class Scyphozoa; Order Rhizostomeae), categorized as either motile (ciliated) or nonmotile types. This inaugural study provides a qualitative assessment of the stinging contents of C. xamachana mucus and implicates mucus containing cassiosomes and free intact nematocytes as the cause of stinging water.