SpaceX: NASA Europa deal reveals the tricky politics of space rockets

The future of NASA’s Space Launch System is in question after another contract win for SpaceX.

Hidden within the icy shell of Jupiter’s moon Europa, there is an ocean — one which may host some form of life. Exploring this watery world is one of NASA’s top priorities for the next decade. That’s why the agency is pouring so much effort into a mission to explore the moon’s oceans — the Europa Clipper — which will launch in October 2024.

But earlier this month, NASA announced it is altering the mission in one critical way. The Clipper will launch SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket and not atop NASA’s flagship launch vehicle, the Space Launch System.

The decision raises new questions about the future of the Space Launch System, which NASA continues to say is a cornerstone of its Artemis program to return humans to the Moon by 2024. It also tells us a lot about the symbiotic relationship between Elon Musk’s SpaceX and the agency.

By opting for SpaceX to launch the Clipper, NASA is flying in the face of the U.S. Congress, which for ten years insisted the Europa Clipper be borne on NASA’s own SLS rocket before giving NASA the right to choose whether to do it or not in late 2020. Given a choice, NASA chose SpaceX.

The choice seems sensible on the surface. The SLS is behind schedule, and launching the Clipper using a private company may be cheaper and more reliable. NASA has also contracted SpaceX to develop a Human Landing System vehicle that will transfer NASA’s astronauts from lunar orbit and to the surface of the Moon.

All of which begs the question: Is the Space Launch System essentially dead on arrival? And, if so, are NASA’s landmark science missions dependent on SpaceX?

Why NASA picked the Falcon Heavy for Europa

The NASA Authorization Act of 2010 sets out that the SLS is the space agency’s flagship launch vehicle for crewed missions and cargo supply trips. It was — and technically still is — the technological and spiritual successor to the retired space shuttle program.

The SLS was supposed to be ready in 2017 for uncrewed flights — it is four years behind schedule at this point. It is supposed to launch NASA crewed missions from 2023 onwards.

In late 2020, Congress changed course, legislating that NASA should only use the SLS to launch the Europa Clipper if the SLS would be ready in time for the scheduled launch date, among other criteria.

According to the source selection document justifying NASA’s subsequent choice of commissioning SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy to launch the mission to Jupiter’s moon instead, NASA clarifies that the agency doesn’t believe the SLS will be ready by October 2024.

NASA looked at proposals from both SpaceX and United Launch Systems, the latter planning to use its Vulcan Centaur heavy-lift rocket to put the Europa Clipper in space. It is also under development.

In descending order of importance, according to the source selection document, NASA considered three factors in choosing a private partner:

- Mission suitability

- Past performance

- Price

As the only rocket available to use right now, the SpaceX Falcon Heavy appears to have been a clear choice. Beyond the existence factor, the Vulcan Centaur also lacks the power to fly the Europa Clipper without significant upgrades. And United Launch System’s bid cost was “significantly higher” than the approximately $178 million NASA will need to pay SpaceX to launch the Clipper.

An artist’s impression of the Europa Clipper at Jupiter’s icy moon.

Price was reportedly the least of NASA’s concerns, but a $178 million SpaceX contract is a lot less money than an anticipated $2 billion-per-flight price tag for SLS, should it ever be ready to launch.

“As NASA moves beyond development for SLS, Orion, and new ground systems, the agency is working to bring down costs,” the agency tells Inverse in a statement.

Does the SLS have a future?

If the SLS has a future with NASA, then it may be with the agency’s upcoming mission to put humans back on the Moon, the Artemis missions.

“I believe the SLS is a temporary rocket,” Laura Forczyk, a space consultant with Astralytical, tells Inverse.

“The only missions that SLS is currently planned for are the first three Artemis missions,” she adds. NASA spokesperson Kathryn Hambleton tells Inverse that this is not strictly true.

“NASA is committed to using SLS and Orion beyond Artemis III,” Hambleton says. “NASA is already building SLS rockets for missions through Artemis V.”

If Artemis I launches as planned in November 2021, the mission will involve an uncrewed lunar flyby using the Orion space capsule. Artemis II will feature a crewed lunar flyby scheduled for September 2023. The capstone of the project, Artemis III, is scheduled for launch in September 2024. If it is successful, Artemis III will put humans on the surface of the Moon for the first time since 1972.

“No other rocket is capable of sending astronauts in Orion to the Moon for the missions we will accomplish under the Artemis program,” Hambleton says.

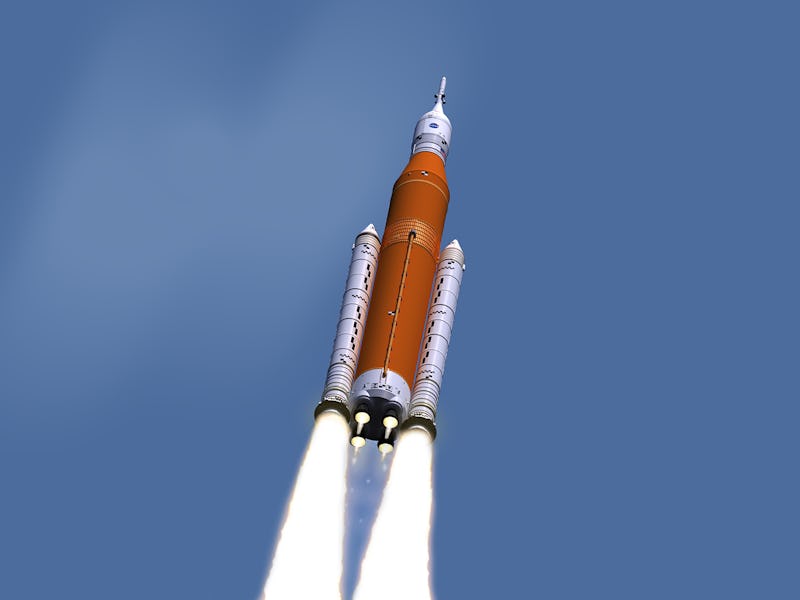

An artist’s conception of the NASA SLS Block 1 crew rocket.

It’s not clear that Orion will be the best vehicle to ferry astronauts to the Moon in the long run.

NASA has awarded a $2.9 billion contract to SpaceX to build the Human Landing System (HLS) component of the Artemis moon program, essentially putting their faith in a modified version of SpaceX’s Starship vehicle to ferry astronauts to the lunar surface.

Starship is more capacious than Orion — SpaceX claims it can carry 100 people into orbit, but Orion can only carry four. Forczyk points out that if Starship works as designed, it could fly astronauts to the Moon, land them there, and return them to Earth — all without using the Orion capsule or the SLS.

That means NASA’s SLS could end up without an essential mission to justify its creation.

“I do see it fading away,” Forczyk says, “probably in the next decade.”

That doesn’t mean the SLS won’t fly at all, though. In fact, Forczyk is certain it will.

“SLS has from the beginning been a political rocket,” she says. “A rocket that the Senate had decided that NASA needed to build to keep NASA expertise and contractor jobs in certain key districts.”

So long as powerful political supporters of the SLS, such as Alabama Senator Richard Shelby and NASA Administrator Bill Nelson are in office, the rocket will continue to be developed — for the time being anyway.

How does NASA’s SLS compare with SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy?

To better understand why NASA would choose SpaceX for the Europa Clipper, it is helpful to break down the vital statistics of the SLS and the Falcon Heavy.

Here’s what you need to know about the SLS:

- The version of the SLS that is supposed to launch the Artemis I mission is the SLS Block 1.

- The SLS Block 1 is a two-stage rocket with a 212-foot tall core.

- It is powered by four RS-25 rocket engines that burn liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen for fuel.

- It has two solid-fuel rocket boosters.

- Together, the core and boosters produce more than eight million pounds of thrust, allowing the vehicle to hoist more than 95 tons into low Earth orbit.

- It is more powerful than Falcon Heavy.

- A modified Delta IV rocket, known as the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage, acts as the SLS Block 1’s upper stage. This is what will propel Orion from low Earth orbit to the Moon.

And here’s how the Falcon Heavy stacks up:

- The Falcon Heavy consists of a 230-foot tall core that is essentially a modified SpaceX Falcon 9.

- The Falcon Heavy comprises the Falcon 9, a two-stage rocket flanked by two more Falcon 9 first-stage rockets, acting as liquid fuel boosters.

- The rocket is powered to orbit by a total of 27 Merlin engines.

- The engines are reusable.

- The Falcon Heavy generates five million pounds of thrust and can lift around 64 tons into low Earth orbit.

NASA SLS timeline: Key facts

When first announced in 2011, the vision was to make the first uncrewed tests flights with SLS in late 2017.

Almost four years after that date, NASA is still in the middle of assembling this 188,000-pound behemoth as of June 2021.

In addition to being behind schedule, the SLS is also projected to be more expensive to operate than the SpaceX Falcon Heavy. SLS launches will run around $2 billion, while the reusable Falcon Heavy launches for $90 million a pop.

These differences flow directly from the SLS’s status as a political project rather than a technical solution to the problem of lofting people and cargo into orbit, according to Forcyzk.

NASA states that people and material from all 50 U.S. states will help to build the SLS. This is “because it is politically beneficial to mention how NASA touches all 50 states, but it is not a way to build a cost-effective rocket,” Forcyzk says.

SpaceX and other private launch providers are not so constrained by patriotism and politics.

This is a reminder that NASA is a political organization run by the U.S. government, Forczyk says. But it’s also a science and technology organization.

“[NASA] will choose the rocket that is the best available, assuming that Congress doesn’t interfere otherwise” for the mission at hand, she says.

“Which is exactly what [NASA has] just done with the Europa Clipper,” she adds.

Europa may have the right conditions to host a form of life.

What’s next — If all goes according to plan, the Europa Clipper will launch for Europa aboard a Falcon Heavy in October 2024 and reached the Jupiter system by April 2030.

An SLS-powered Clipper, if NASA had gone that route, could have powered the Europa Clipper to Jupiter a little faster, by August 2027, according to a presentation made by Europa Clipper Project Scientist Robert Pappalardo in 2020.

But the SLS will be sticking to the Artemis program, with Artemis I scheduled to launch an uncrewed Orion space capsule to the Moon, orbit it, and then come back to Earth in November 2021.

It will then power the Artemis II and III missions in 2023 and 2024, respectively. Of course, the rocket is still not fully built at the time of writing.

Ultimately, Forczyk believes it would take a lot to keep the SLS rocket from being the one to fly these critical Artemis missions to space — albeit maybe not this year.

“The only thing I can see happening that would kill it would be complete, absolute complete failure,” she says, “and that would be unfortunate because a lot of really good people have worked on the program.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated following additional comments from NASA.

This article was originally published on