This unexpected force may be responsible for life on Earth

The finding increases the chances of habitable planets around Sun-like stars.

Luke Daly wants you to think about the Sun every time you drink a glass of water.

“There’s a little bit of sunshine in that glass of water,” Daly tells Inverse.

Daly, a professor at the University of Glasgow’s School of Geographical and Earth Science, and an international team of researchers recently suggested that it wasn’t just space rocks that seeded the Earth with water, but solar winds played a significant role as well.

The new findings not only help us understand our origin story, but suggest life may be more common throughout the universe.

Daly and his co-authors published their findings in the journal Nature Astronomy.

HERE’S THE BACKGROUND — Earth is the only known planet to host life, yet scientists are still unsure how life came to be — and later thrive — on this planet.

“Understanding the origin of water on Earth and sort of how you build habitable planets is kind of one of the big unknown questions in planetary science right now,” Daly says. “And that's what kind of really sets planetary science apart from other disciplines is we are missing these big picture unifying theories that would sort of help us explain how you build a solar system.”

Several studies have suggested that asteroid impacts during the early history of the Solar System are the primary source of water on Earth. These massive space rocks carried organic molecules to the planet when they crash-landed on it.

But asteroids alone couldn’t account for all the water on Earth; something wasn’t adding up.

Water-rich asteroids have slightly more heavy hydrogen as part of their composition than Earth’s water, while the remaining asteroids don’t have enough water in them.

On the other hand, the Sun has very low levels of heavy hydrogen, also known as deuterium.

“Obviously, we can't put bits of the Sun directly into the Earth because that’d be bad for everybody involved,” Daly says. “So that's why the solar wind idea is really nice because the hydrogen coming from the solar wind comes from the Sun, it will have this very light, deuterium-poor water ratio, and that's enough to basically balance the heavy water from water-rich asteroids.”

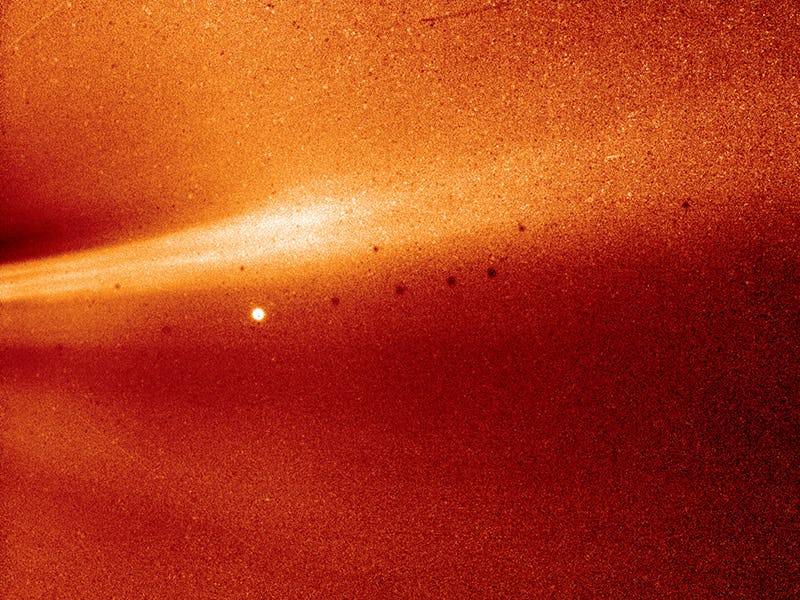

An Apollo 7 image of the Sun raining its rays down on Earth. Just imagine this, but wind, and you kinda get it.

WHAT’S NEW — The team behind the new study wanted to prove the Sun’s role in delivering water to Earth.

To do that, they got their hands on asteroid samples returned by the Japanese mission Hayabusa in 2010. The team then examined the “damage layer,” which was struck by space weathering, which includes solar wind.

The outer layer had H2O molecules, which could have only gotten there by solar wind.

“We showed that you can implant quite a lot of water into these tiny dust particles by the solar wind,” Daly says.

In the early Solar System, as these asteroids were falling down onto Earth, they were also smashing into each other in space, producing a cascade of dust. The solar wind then struck the dust.

“So the early Solar System was an incredibly dusty place,” Daly says. “There’s tons and tons of tiny dust particles flying around alongside these asteroids, getting impacted by a very young energetic Sun ... getting implanted with all this water.”

“And then as the Earth is kind of going around, it will sweep up that dust alongside those water-rich asteroids, producing quite a substantial reservoir of water on the Earth from just that dust alone,” he adds.

WHY IT MATTERS — The recent study not only helps scientists put together pieces of the puzzle of how life began on Earth, but it also informs their search of potentially habitable planets across the universe.

Daly says the findings increase the chances of finding life, or at least water, on planets that orbit within the habitable zone around a Sun-like star, if indirectly. Evidence has shown that Mars, for instance, used to have flowing water on its surface.

But for life to survive, different elements need to come together on a planet.

“You need a little bit of everything,” Daly says. “A little bit of space dust, a little bit of asteroids to build a habitable world.”

Abstract: The isotopic composition of water in Earth’s oceans is challenging to recreate using a plausible mixture of known extraterrestrial sources such as asteroids—an additional isotopically light reservoir is required. The Sun’s solar wind could provide an answer to balance Earth’s water budget. We used atom probe tomography to directly observe an average ~1 mol% enrichment in water and hydroxyls in the solar-wind-irradiated rim of an olivine grain from the S-type asteroid Itokawa. We also experimentally confirm that H+ irradiation of silicate mineral surfaces produces water molecules. These results suggest that the Itokawa regolith could contain ~20 l m−3 of solar-wind-derived water and that such water reservoirs are probably ubiquitous on airless worlds throughout our Galaxy. The production of this isotopically light water reservoir by solar wind implantation into fine-grained silicates may have been a particularly important process in the early Solar System, potentially providing a means to recreate Earth’s current water isotope ratios.

This article was originally published on