Science explains that breathtaking, viral mola mola video

You may remember this fish from another viral moment in 2015.

In California's Monterey Bay, locals were recently treated to an unusual spectacle: a school of ocean sunfish, Mola mola, flapping around in the bay's Breakwater Cove.

Also known as the ocean sunfish or common mola, these fish don't typically show up in such large groups within the harbor — so Inverse asked mola expert Michael Howard, a senior aquarist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, to explain.

A viral tweet posted by local news team KSBW shows the group of mola, discovered during a field trip. There were at least 100 of fish in the group, Howard says.

These molas are young, Howard explains. At less than a foot long, they're nowhere near the five- to six-and-a-half footers he has come across in the bay.

While big molas tend to be loners, it's not unusual for the common mola to hang out in big groups when they're smaller, Howard says. They form schools ranging into the thousands when they're far offshore. But it's not typical for a group this big to hang near the harbor.

The reason for the big school isn't totally clear, Howard says — but it's likely that windy conditions in the ocean stirred up deep, cold water, prompting the fish to seek warmer water in the shallow harbor.

Howard says he hopes the fish won't hang around too long; the common mola has to be on the lookout for predators like the large sea lion population in Monterey Bay. Those sea lions tend to hang out near the piers and jetty in the harbor, he says, meaning the molas are at risk being closely confined in the area.

Big fish — A fully-grown Mola mola can reach more than eight feet, pushing 5,000 pounds, Howard says. That's a ridiculous size, but their relatives, Mola alexandrini, can get even bigger.

That means the fish in the Monterey Bay video will likely grow about three times as large in their lifespan.

Mola mola with a diver near Punta Vicente Roca.

Because of their enormous size, some people mistake Mola mola for sharks, Howard says, because they see a dorsal fin breaking the water's surface. But shark fins are fixed, while a mola's fin can flap around — the fish uses its dorsal and anal fins to push forward in the water.

The look of a Mola mola can be confounding, too. It seems, at a glance, like these fish just kind of float and flap around at the water's surface. But they're actually active swimmers, according to researchers who have tagged and observed the fish diving deep to forage for prey like jellyfish.

"When they are resting at the surface they are allowing their bodies to warm in the warmer surface waters while actually using the energy of the sunlight to speed this process, hence the name ocean sunfish," Howard says.

That seems to be what the Mola mola was doing in another viral video, which circulated in 2015. Two Bostonians came across the common mola while fishing, believing at different times that they were witnessing a baby whale tuna, flounder, or just a dead fish.

Mola mola getting a snack from a boater.

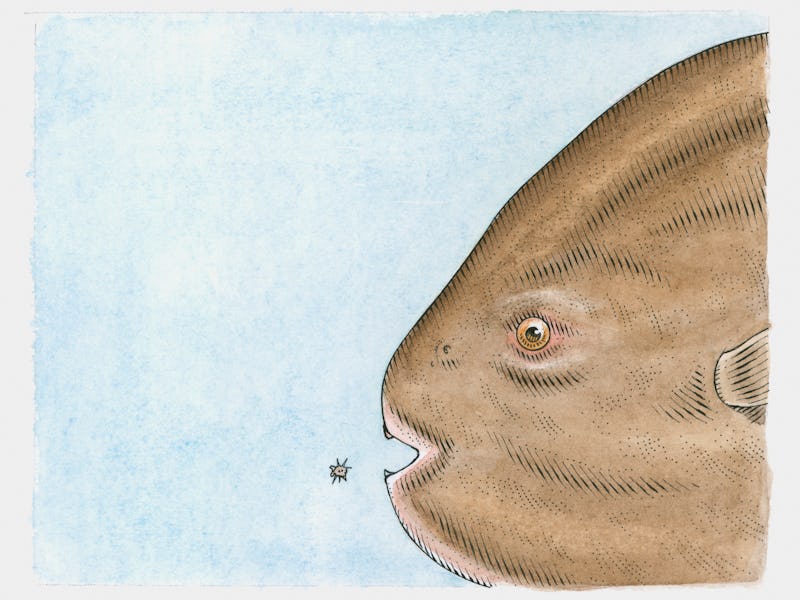

In defense of the ocean sunfish — To some people, this odd-looking fish is proof that nature doesn't always get it right: The common mola is flat and heavy, with a gaping mouth, big eyes, that can make it seem like there's not a whole lot going on upstairs.

As Florida diver Bryan Clark told Inverse in 2016, the fish doesn't even seem like it was finished being built.

"It really looks like the head of a fish, rather than a whole fish itself," Clark said, describing the mola's body as like the "hardest rubber" you've ever felt.

Some have a harsher take on the bony fish. In 2017, a now-deleted Facebook post went viral, condemning the Mola mola, as a "big dumb idiot" that swims and preys poorly, only surviving thanks to its massive births of 300 million eggs.

But this take simply doesn't do the fish justice, Howard says; it may look somewhat aloof, but the mola is actually well-equipped for survival.

"Actually, they are keenly aware of their surroundings able to find prey and avoid predation to grow into the biggest teleosts in the ocean," Howard says. "Also, in an aquarium setting, they can be trained and learn to respond to cues which suggests that they are indeed ‘smarter’ than the general public gives them credit for."