After Almost 8 Years, Saturn Is Entering Autumn — These New Webb Telescope Images Reveal Its Foliage

Imagine seven years of Halloween and pumpkin spice.

If there were a Starbucks on Saturn, it would be rolling out the pumpkin spice right about now. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) recently captured images of Saturn’s late summer slowly fading into fall.

Saturn’s seasons are 7.5 years long. It’s been summer in the northern hemisphere since Cassini’s last days in 2017, but now summer is coming to an end. JWST recently caught a glimpse of what the change of seasons on Saturn looks like. University of Leicester planetary scientist Leigh Fletcher and his colleagues published their work in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

Turn, Turn, Turn

Fletcher and his colleagues used the Mid-Infrared Instrument, or MIRI, to capture three quick images of Saturn’s upper cloud layers, spanning the nearly 60,000 miles between the gas giant’s north pole and its equator. The MIRI data helped the team measure the temperature in Saturn’s upper layers of clouds and see which chemical compounds are swirling around in its atmosphere. It turns out that the northern hemisphere is slowly cooling, and the global air circulation that drives Saturn’s weather is preparing to reverse directions.

Like Earth, Saturn spins on a slightly tilted axis (ours is off-kilter by about 23.5 degrees, while Saturn’s is tilted about 26.7 degrees). A slight tilt in the planet’s axis is the reason for the season; as a planet orbits the Sun, its axis wobbles slowly, pointing one end at the Sun for part of the year, and the other end for the other part of the year. Whichever hemisphere is pointed toward the Sun gets to bask in the warmth of summer, while the other hemisphere enjoys the brisk chill of winter. Because Saturn takes about 29 years to finish one long lap around the Sun, its seasons are also long, and the change, when it comes, is slow.

But it’s well worth watching.

This image shows the four areas of Saturn MIRI imaged in November 2022.

Winter is Coming

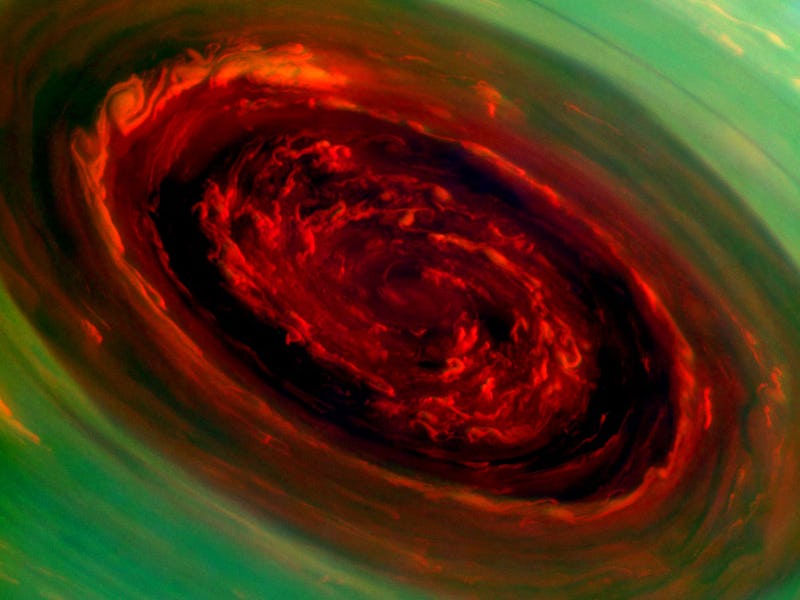

At Saturn's north pole, a gargantuan hurricane rages, fenced in by a hexagon-shaped vortex. As winter sets in, the warm air currents driving that vortex will fade and finally sputter out. Before that happens, though, the north pole will already be pointed away from the Sun, hidden in the darkness until spring comes in a few years.

Cassini discovered the vortex late in its mission, during springtime in Saturn's northern hemisphere. Around the same time, Cassini's instruments watched a circular vortex (which had swirled around the planet's south pole since Cassini arrived at the height of southern summer) slowly fade as winter overtook the south. The same fate awaits the vortex now swirling around the upper layers of the northern atmosphere, according to Fletcher and his colleagues.

But Saturn's north pole will keep its iconic hexagon of jet streams. Cassini discovered two hexagons — or maybe two parts of the same hexagon — in Saturn's far north. One circulates deep in the clouds and may be churned up by the gas giant's rotation, and it's not going anywhere; Voyager 1 was first spotted in 1981, and it's been stable ever since.

We may also get to see Saturn's north pole change colors just before it vanishes into darkness. As northern spring slid toward summer, between 2012 and 2016, Cassini's instruments watched the space inside Saturn's hexagonal vortex change from light blue to golden yellow. That's because during the summer months, ultraviolet light reacts with hydrocarbons in the upper atmosphere to create a haze (a lot like smog here on Earth). But during the cooler, darker winter months, the haze clears, leaving behind blue skies.

A Change in the Wind

During the long Saturnian summer, warm air rises in the clouds of whichever hemisphere is basking in the Sun’s warmth. Those warm currents drift across the equator toward the winter half of the planet, where they cool and slowly sink into the cloudy depths. Since the air on Saturn is laden with hydrocarbons, that means the winter half of the planet ends up with more hydrocarbons floating in its clouds, while the summer half gets clearer skies.

The Cassini spacecraft watched that global weather pattern reverse itself as Saturn’s most recent northern winter ended, starting in 2009. Huge air currents that had flowed from the southern hemisphere to the north switched directions. Now, JWST offers a glimpse of that process slowly reversing itself again as the seasons change.

We probably won’t get to watch this process in as much detail as Saturn’s last turning of the seasons. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission with a daredevil dive into Saturn’s clouds in 2017, and there’s no other spacecraft in Saturn’s orbit to keep an eye on the planet’s changing seasons. JWST images like these are probably the best look at Saturn we’re going to get for the foreseeable future — and those are likely to be few and far between.

For one thing, there’s already more space and more fascinating (and sometimes deeply weird) things happening out there than JWST can observe. Astronomers compete fiercely for a few hours of the telescope’s time. Our Solar System is on JWST’s to-do list, but that’s very different from having a dedicated mission like Cassini to focus on a single planet.

Photographing planets is also very difficult for JWST. The telescope was designed to capture images of very faint objects that are very far away; planets and other objects here in our Solar System are so bright that the sunlight they reflect can overwhelm JWST’s instruments if its operators aren’t very careful, and they’re so close that their movement can be hard for the telescope to keep up with. Despite that, JWST has produced some stunning images of objects in our Solar System, and there will be more.

We just probably won’t get to watch Saturn’s seasons change in real-time.

This article was originally published on