The nearest star to us may be too hellish for life. Here’s why.

Proxima Centauri has a potentially habitable exoplanet. But the temperamental star may have fried that “potentially” away.

Proxima b, the closest exoplanet to our Solar System, has been a focal point of scientific study since it was first confirmed (in 2016). This terrestrial planet (aka rocky) orbits Proxima Centauri, an M-type (red dwarf) star located 4.2 light-years beyond our Solar System – and is a part of the Alpha Centauri system. In addition to its proximity and rocky composition, it is also located within its parent star’s habitable zone (HZ).

Until a mission can be sent to this planet (such as Breakthrough Starshot), astrobiologists are forced to postulate about the possibility that life could exist there. Unfortunately, an international campaign that monitored Proxima Centauri for months using nine space- and ground-based telescopes recently spotted an extreme flare coming from the star, one which would have rendered Proxima b uninhabitable.

The campaign was led by Meredith A. MacGregor, an assistant professor of astrophysics from the University of Colorado Boulder, and included members from the Carnegie Institution for Science, Sydney Institute for Astronomy (SIfA), CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science, Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), and multiple universities.

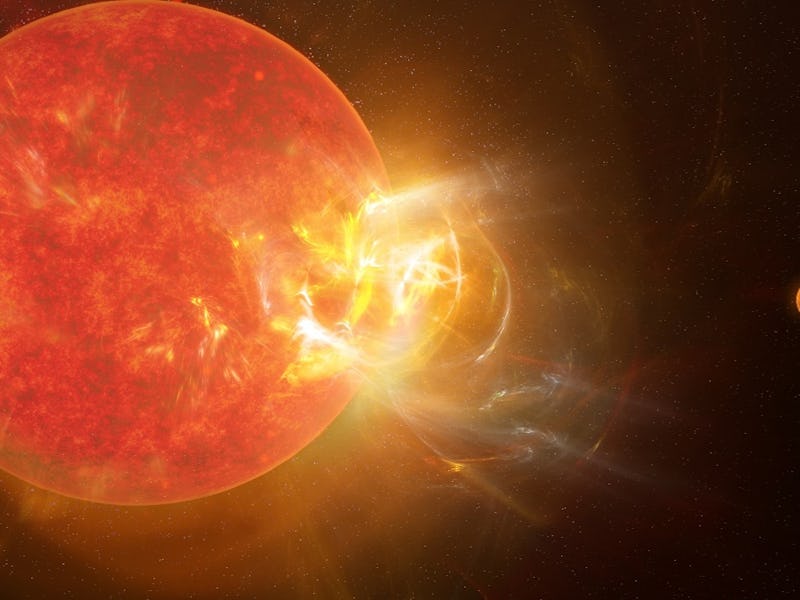

This artist’s impression shows the planet Proxima b orbiting the red dwarf star Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the Solar System.

M-type stars like Proxima Centauri are a class of low-mass, low-luminosity stars that are known to be variable and unstable compared to other classes. In particular, these stars are prone to flare-ups, which occur when there’s a shift in their magnetic fields that accelerates electrons to near light-speed (NLS). These electrons interact with the star’s plasma, causing an eruption that produces emissions across the entire electromagnetic (EM) spectrum.

To determine how much Proxima Centauri flares, the research team observed the star for 40 hours over the course of several months in 2019. This included the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP), Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), Hubble Space Telescope (HST), Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), and the du Pont Telescope.

These telescopes recorded a massive flare on May 1st, 2019, capturing the event as it produced a wide-EM spectrum of radiation and tracing its timing and energy in unprecedented detail. As MacGregor explained in a recent Carnegie Science press release:

“The star went from normal to 14,000 times brighter when seen in ultraviolet wavelengths over the span of a few seconds… If there was life on the planet nearest to Proxima Centauri, it would have to look very different than anything on Earth. A human being on this planet would have a bad time.”

Since red dwarfs are rather dim compared to other types of stars, flare-ups are not likely to produce much in the way of visible light. Ordinarily, astronomers consider themselves lucky if they can observe flares of this kind with just two instruments. This campaign was the first time that astronomers were able to get multi-wavelength coverage of a stellar flare, which allowed them to observe the huge surges in ultraviolet and millimeter-wave radiation.

Artist’s depiction of the interior of a low-mass star, such as the one seen in an X-ray image from Chandra in the inset.

The team’s findings, which appeared in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on April 21st, constitute one of the most in-depth anatomies of a flare from any star in our galaxy. In the future, these signals could help researchers gather more information about how stars generate flares, which could have immense implications for exoplanet and habitability studies. Unfortunately, it does not bode well for planets like Proxima b.

This research is the latest in a series of papers and studies conducted since Proxima b was discovered that indicate how the system is not suitable for life. As the closest exoplanet to Earth, and located in the star’s HZ, Proxima b is the most likely candidate for follow-up observations and astrobiological surveys. But according to this latest study, the flares it emits would have likely rendered the planet sterile a long time ago. As Weinberger explained:

“Proxima Centauri is of similar age to the Sun, so it’s been blasting its planets with high energy flares for billions of years. Studying these extreme flares with multiple observatories lets us understand what its planets have endured and how they might have changed. Now we know these very different observatories operating at very different wavelengths can see the same fast, energetic impulse.”

Beyond Proxima Centauri, the findings could also have implications for all planets that orbit within the HZs of red dwarf stars. M-type dwarfs are the most common type of stars in our galaxy and account for about 70% of stars in the entire Universe. Of the over 4,375 exoplanets that have been confirmed to date, a statistically significant number of the “Earth-like” planets have been found orbiting M-type dwarfs.

An artist’s illustration of a hypothetical exoplanet orbiting a red dwarf.

This has led many astronomers to speculate that the best place to find potentially habitable rocky planets is in red dwarf star systems. For this to be true, most of these stars would have to be significantly less active than Proxima Centauri. On a more positive note, the research suggests that our closest stellar neighbor could have more surprises in store for astronomers, like previously unknown types of flares that demonstrate exotic physics.

This research was conducted with support provided by the NASA Goddard Space Center.

This article was originally published on Universe Today by Matt Williams Read the original article here.

This article was originally published on