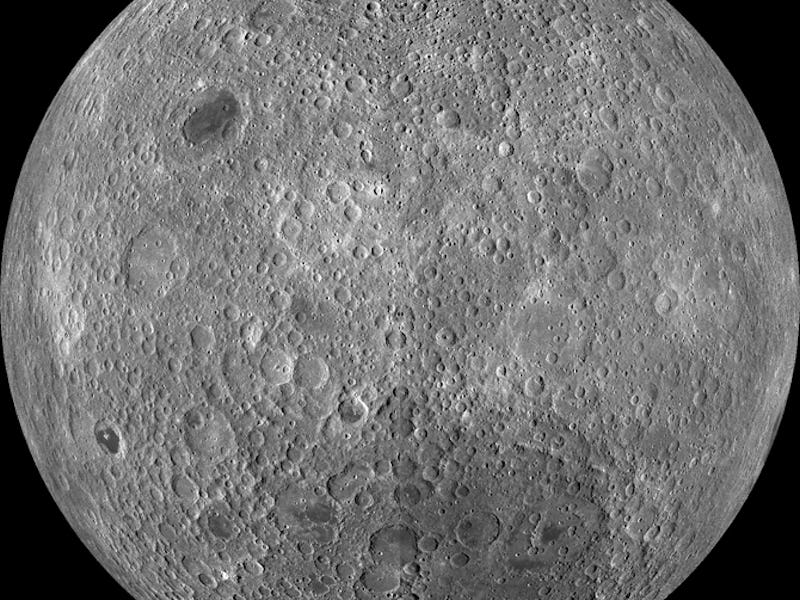

On the far side of the Moon, China's lunar lander makes a game-changing discovery

"It’s a completely different world."

On January 3, 2019, China’s Chang’e 4 landed on the far side of the Moon. Since then, the lander has been busy making the first direct measurements of this mysterious side of our closest neighbor.

Now, researchers have released the unprecedented treasure trove of data for the world.

The data give scientists an unparalleled look at the structure of the far side of the Moon, one that is just impossible to get from satellites or other, older lunar landers, all of which have touched down on the near side.

By probing deep into the Moon's rugged terrain, the lander reveals the first high-resolution imaging of the Moon's subsurface, allowing scientists to analyze its composition, layer by layer.

According to the new data, the far side of the Moon is covered by a layer of loose deposits that run up to 12 meters thick, also known as lunar regolith. This is the first time scientists have been able to confirm that lunar regolith exists on both sides of the Moon.

“Going on the far side is very interesting," Elena Pettinelli, professor at Università degli studi Roma Tre and a co-author of the new study, tells Inverse.

"The near and far sides are very different on the Moon. It’s a completely different world," she says.

The data allow scientists to reconstruct the history of impact craters on the far side of the Moon for the first time. This helps paint a better picture of planetary formation in the early universe and informs preparations for future missions to the Moon, including manned ones like NASA's 2024 Artemis mission.

The new data was published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

Lunar probing

In the new study, researchers used a combination of high-resolution imaging and ground-penetrating radar scans to analyze the different layers of Moon’s subsurface.

The lander provided high resolution radar imaging of the different layers of the moon's substructure.

On the Moon, Chang'e 4 was able to penetrate up to 40 meters deep.

“The penetration of 40 meters is quite something,” Pettinelli says. “The material was extremely transparent, and we could see the layers quite well.”

The first layer of the Moon's surface is around 12 meters deep, and is composed of very fine regolite (loose rocks) composed of very small rocks.

After that initial layer, the researchers discovered blocks of harder material mixed with finer material. These are identified as ejecta deposits.

Ejecta deposits surround a lunar crater, and are believed to be the material ejected from the impact that created the crater.

Prior to the radar imaging, scientists only glimpsed ejecta deposits via images collected by orbiting satellites, Pettinelli says.

Understanding how these deposits form helps scientists gather the history of impacts on the Moon that occurred during the early formation years of the Solar System.

“We always hypothesized how ejecta deposit was made, but this is a very clear image of the deposit below,” she says.

Chang’e 4: The lander that changes everything

Chang’e 4 launched in December, 2018. it is the fourth lunar mission by China’s space agency and the only one to land on the Moon's far side ever. The first two missions were orbiters, and the third was an orbiter-rover hybrid that landed on the near side of the Moon.

Chang'e 4's landing was no mean feat in itself. The reason why it is so difficult to send anything, robot or man, to the far side of the Moon, is because it is difficult to maintain communications with ground control on Earth with a giant rock in between (the Moon!).

Just beyond the tip of the right arrow is the Chang'e 4 rover and the lander is to the right of the tip of the left arrow.

The rover landed in the Von Karman crater, located near the Moon’s south pole. This area is of particular interest to scientists, as it holds water ice, which may one day be used as a resource for long-duration, manned missions to the Moon.

“It is clear that this is the area where future human landers will go,” Pettinelli says. “If you start thinking about staying longer, you have to think of a source of water.”