NASA will smash a spacecraft into an asteroid Monday — what you need to know

The DART mission doesn't have much aboard — and that's kind of the point.

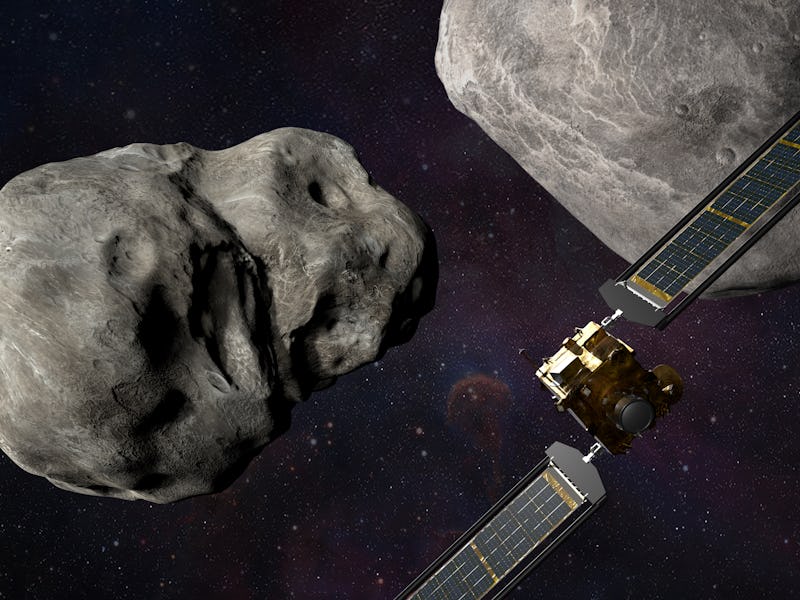

On Monday, NASA will test out a concept straight out of Hollywood: seeing if we could deflect an asteroid heading for our planet by smashing into it with a spacecraft. At the 2022 Europlanet Science Congress this week, researchers from the mission shared details about not only how they’re going to crash the Double Asteroid Redirect Test (DART) spacecraft into the asteroid — but also how they’re going to tell if their mission succeeded.

“We are going to go to a double asteroid — the binary asteroids Didymos and Dimorphos — and we are going to change the orbit of Dimorphos around Didymos by redirecting it,” Andy Rivkin, DART Investigation Team Lead at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, said as he summed up the goals of the mission. “This is an experiment at the kind of scales that we might use if we ever needed to deflect an asteroid for real.”

But the DART mission is just the beginning of our exploration of Dimorphos and Didymos — it will have the help of several robotic companions, including a to-be-launched European mission in a few years time.

DART mission time and how to watch

DART’s collision with Dimorphos is set for 7:14 p.m., Eastern time on Monday, but NASA will begin livestreaming it at 6 p.m.

DART has a camera on board called the Didymos Reconnaissance and Asteroid Camera for Optical navigation (DRACO) which will primarily be used for navigation, but will also collect footage of the asteroid as the spacecraft approaches it. Once the collision happens, though, these on-board systems won’t be in any fit state to collect more data.

DART recently deployed its own small photography satellites called Light Italian CubeSat for Imaging of Asteroids or LICIACube. With two optical cameras on board, this CubeSat will hang out near to the impact site to snap images of the impact’s immediate effects, to confirm that the impact actually occurred and to see the plume of material thrown up by the impact and the crater it forms.

DART mission objectives

The asteroid pair aren’t really a threat to Earth, though they do pass relatively close to our planet. At the time of impact, they will be almost 7 million miles away from Earth. That means they are difficult to see, even with accurate instruments.

“From the Earth, Didymos and Dimorphos are both too close together and two small to be seen as more than just a point of light,” Rivkin said.

To see what effects the impact of DART will have on the asteroids, mission scientists will need to use some specialist tools, including an international network of large, ground-based telescopes across all seven continents. There will be measurements coming in from space-based telescopes like the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope as well. Even NASA’s Lucy spacecraft, which is on its way to visit the Jupiter Trojan asteroids, will observe the asteroid binary.

“Since [the asteroids] only appear as one point of light to telescopes, we’re going to watch the brightness of that point of light go up and down,” Rivkin said. “As Dimorphos goes behind Didymos, the brightness drops a little bit, and it comes back up when it reappears. When Dimorphos moves in front of Didymos, we can see again a brightness drop due to the shadow.”

By looking at the time it takes for these changes in brightness to occur, the researchers can see how long it takes the two asteroids to orbit each other. And they can compare this orbital period from before and after the DART impact to see what difference it makes.

HERA, an ESA follow-on to DART, will launch in a few years.

HERA mission: ESA’s follow-up to DART

But researchers need more detailed information on how the asteroid is changed by the DART impact if they ever hope to use such a concept in a real Earth-threatening emergency. The mission will be collecting information up close as well.

But there’s only so much information that a small CubeSat with two cameras can gather. To truly understand the changes which happened in the impact, planetary scientists need a second spacecraft to go and look at the wreckage. That’s the job of Hera, a European Space Agency mission that will launch in 2024 to visit the asteroids in 2026.

Once it arrives at the asteroid system, Hera will begin by taking a global view of the pair from a safe distance to observe features like their shape and mass. Then Hera will deploy its own pair of small CubeSats to investigate them in more depth, and will circle in closer and closer to the asteroids before landing on them.

One of Hera’s big goals is to measure the mass of the smaller asteroid Dimorphos. Though we know the mass of the larger Didymos, the mass of the smaller “moonlet” is still unknown, and this information is of vital importance. “We need it to be able to evaluate how efficient the momentum transfer from the spacecraft to the asteroid is,” Michael Küppers, Hera Project Scientist at the European Space Astronomy Centre, said.

This lets the researchers know how much the asteroid was deflected, and along with more data Hera will gather on the asteroid’s physical properties, will let us predict whether this kind of deflection could be enough to nudge a real potentially dangerous asteroid away from its path toward Earth.

Finding out whether we really can crash spacecraft into asteroids to protect the planet will be a long-term endeavor, and we will have to wait several years for Hera data to know the full effects of the DART impact. But for those who can’t wait, there will be first data available from the impact within days or weeks.

“We’ll know pretty quickly whether DART hit or not,” Rivkin said, with rough information on how the impact changed the asteroid’s orbit coming shortly after. But he emphasized the experimental nature of the mission, as there are unknowns varying from the angle at which the spacecraft impacts the asteroid, to the asteroid’s shape and internal composition, to the ground texture of the asteroid, all of which can affect the outcomes.

The many unknowns are part of what makes this mission so exciting, as it gives researchers a chance to learn about asteroids and impact craters as well as practicing planetary defense strategies.

“We’re open to a lot of different outcomes being interesting and helping us understand the planetary defense implications of what we’re doing,” Rivkin said.