New evidence shows more than one asteroid could have killed the dinosaurs

Newly-discovered crater suggests the Chicxulub impact may have been part of an encounter with an asteroid cluster.

Geoscientist Uisdean Nicholson and his colleagues weren’t looking for evidence of an ancient disaster when they found Nadir Crater. They were interested in a much older, much slower event: the gradual breakup of a supercontinent starting around 140 million years ago.

But seismic data from the submerged continental shelf, off the coast of modern Guinea and Guinea-Bissau in western Africa, threw the researchers a meteor-sized curveball. And as they dug into the research more, they realized the discovery could rewrite what we know about the extinction of the dinosaurs.

"The discovery of the crater was really pure serendipity," Nicholson, a professor at Heriot-Watt University in the United Kingdom, tells Inverse.

What’s New — The 8.5-kilometer-wide Nadir Crater lies atop what geologists call the K-Pg boundary: the layer of rock that marks the end of the Cretaceous Period, the last age of the dinosaurs. If Nicholson and his colleagues are correct, that means a 400-meter-wide meteor hit the African coast sometime within a million years of the much larger meteor impact that killed off most of the non-avian dinosaurs.

“It raises the questions of whether there may have been an impact cluster at the end of the Cretaceous period,” Nicholson and his colleagues write in their recent paper.

The 12-kilometer-wide asteroid that smashed into what’s now Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, forming the Chicxulub Crater, blasted tiny particles of debris into the atmosphere, plunging the planet into a frigid 18-month-long night followed by a chilly five to 10 years. By the end of that long impact winter, 75 percent of the plant and animal species on Earth were gone forever. Of the dinosaurs, only the ancestors of modern birds remained.

Where does Nadir Crater fit into that story? In a way, it almost doesn’t. The Chicxulub impact was more than enough to trigger our planet’s fifth mass extinction; a smaller meteor striking off the coast of Africa feels like overkill — and overkill that would be barely noticeable against the sheer scale of the cataclysm set off by the meteor strike at Chicxulub, then 5,500 kilometers away.

“It’s such a tiny thing on top of a very large thing,” University of Texas geophysicist Sean Gulick, co-author of the recent paper announcing the discovery, tells Inverse. “It doesn’t make sense to talk about it in terms of the extinction event.”

But Nadir Crater could add an interesting twist to the biography of the dino-killing asteroid itself. A second meteor strike, so close in time to Chicxulub, could be just a coincidence. On the other hand, it could suggest that around 66 million years ago, Earth’s orbit carried it into a cluster of asteroids, called an asteroid “family,” and at least two of them scored direct hits. That could mean that for days or weeks, Earth’s skies rained space rocks.

“What’s interesting to think about, if this were the same age, or a few days apart like the Shoemaker-Levy collision with Jupiter, is that there may also have been other fragments — other undiscovered craters out there,” Nicholson tells Inverse. “The more we find out about the event, the more of a complete picture we can build.”

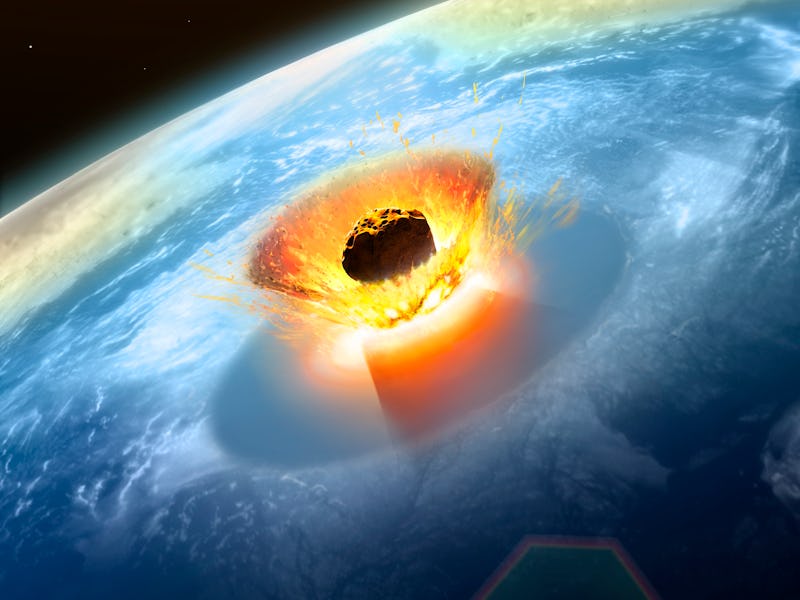

Based on seismic data and computer models, this illustration summarizes the impact that formed Nadir Crater.

Digging Into The Details — Nicholson and his colleagues were poring over seismic reflection data (images of the structure beneath Earth’s surface, made by measuring the speed and angle of seismic waves passing through the layers of rock) when they found the crater.

“I had the data for another project,” says Nicholson. “Some colleagues and I were planning on submitting an International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) proposal to drill in the region, to understand the separation of South American and Africa, and the impact of that event on global climate, ocean circulation, and ecosystems.”

Each image is a vertical cross-section, slicing down through layers of rock. And in two of those slices, the geoscientists noticed features that looked strikingly like an impact crater. Like other large impact craters, it had a raised outer rim and a peak rising up from the center, where rock shoved toward the rim had fallen back toward the middle of the crater, causing it to rebound upward. For 12 kilometers around the site, the rock was fractured and tilted inward toward the crater. And the force of the impact had broken or warped rock layers 700 meters deep beneath the crater floor.

And the crater floor lay just on top of a layer of rock dating back to the very end of the Cretaceous period, 66 million years ago. About 200 kilometers away from Nadir Crater, geologists had previously drilled a well and located the K-Pg boundary — the layer associated with the mass extinction — in it.

“If you map that same layer across, it gets to this crater,” says Gulick. But thanks to the limited resolution of the seismic imaging, estimating the age of the crater comes with about a million years’ worth of uncertainty.

The Nadir Crater object could have hit just moments after Chixulub, or hundreds of thousands of years later. Nicholson and his colleagues eventually hope to drill down into the crater for the answers.

Why It Matters – Either possibility could tell us something interesting about our planet’s history of mishaps and near-misses — and help us refine our estimates of how often large asteroids crash into us.

“There’s an interesting problem that we know we should have lots and lots of impacts on Earth over the history of the planet,” says Gulik, “but because we have a very active surface, due to plate tectonics and erosion, we don’t have that record that should exist.”

Only 15 percent to 25 percent of large impact craters have been preserved, geologists estimate. So every crater that’s discovered is a rare piece of our planet’s past, full of potential clues about how the population of Near-Earth Objects has changed over time, how often objects of different sizes tend to collide with our planet, and what effect those collisions had.

This photo shows scientists working with rock samples drilled from Chicxulub; Nicholson and his colleagues will use similar methods to study Nadir Crater.

If Nadir and Chicxulub turn out to be chunks of the same “parent” asteroid, which crashed into Earth just days or weeks apart, they would be just the second evidence of a cluster impact in Earth’s geological record (although that record is far from complete when it comes to impact craters). The other dates back to the Ordovician period, more than 450 million years ago.

“There is another documented example on the Moon in the Proterozoic (before life began on Earth), but it’s not preserved on Earth — although Earth is highly likely to also have been affected,” says Nicholson.

“If confirmed, then the impact cluster hypothesis would have important implications for our understanding of the frequency and cascading environmental consequences of impact clusters in Earth’s history,” write Nicholson and his colleagues in their paper.

What’s Next — In 2024 or 2025, Nicholson and his colleagues hope to drill down 300 meters into the seabed off the coast of Guinea to get samples of the rock layers that make up Nadir Crater. Those samples could help confirm whether the crater is really the product of a meteor strike or something else, like a collapsed volcanic caldera.

“I think it's an impact crater; it has all the morphology of it,” says Gulick, “but we need to prove it by drilling into it and looking for those diagnostic things like shocked minerals that can only exist in impact craters.”

They also hope to date layers of rock from the crater to see how closely its timing lines up with Chixulub. “You know, maybe we'd be lucky and find the Chicxulub ejecta in the crater, and we could get the exact timing,” Gulick suggests.

The samples might also allow the geoscientists to compare the chemical makeup of the meteors that crashed at Chicxulub and at Nadir. If the timing is relatively close, and the chemical makeup of the two meteors is similar, that suggests they may once have been part of the same object, which broke apart either during a collision or under the influence of Earth's gravity on an earlier orbit before the final, deadly one.

And Nadir Crater may hold clues about what happened in the wake of all that death and destruction.

“Part of the Nadir drilling goal is to analyze the sediment that was deposited onto Nadir over time,” University of Arizona planetary scientist Veronica Bray, a co-author of the study, tells Inverse. “When did life recover? How?”