Why NASA needs to return to a moon they haven’t visited in 35 years

Miranda is a Solar System enigma — and maybe the most unexpected place we could actually find life.

On January 24, 1986, NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft flew by Uranus, getting as close as 50,600 miles to the ice giant and its 27 moons.

Back on Earth, Mark Hofstadter was a first-year graduate student at Caltech, where NASA had set up a special communication link between its Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the university’s astronomy department.

“We were in the classroom watching these images come down,” Hofstadter tells Inverse. “And as soon as we saw the first images of [Uranus’ moon] Miranda, my professor jumped on the table and yelled, ‘What is that?’”

Since then, Hofstadter, who is now a planetary scientist at JPL, has been fascinated by the moons of Uranus, advocating for a return mission to explore their subsurface oceans, geological activity, and unusual composition.

Voyager 2 launched on August 20, 1977, with a mission to do something no spacecraft had done before: visit all four of the Solar System’s outermost planets before heading off to interstellar space.

Voyager 2 did a flyby of planets of the Solar System before heading into interstellar space

The spacecraft’s rendezvous with Uranus lasted for 45 hours, and Voyager 2 captured images and unprecedented observations of the moons that orbit the ice giant. That 1986 visit was the first — and only — close encounter we have ever had with Uranus.

Hofstadter recently co-authored a paper calling for a near-future spacecraft exploration of Uranus’ moons. It would need to launch before the year 2030 for an orbital window to facilitate a smoother journey to the distant planet.

“By flying a new, more capable spacecraft to Uranus,” Hofstadter says, “we can really learn some details about these satellite ocean worlds, how are they interacting dynamically with each other, what are they made of, and their geology.”

We have the technological capabilities to reach Uranus and its moons, he argues, but it is a question of the will, and the funding, to do it that is holding a mission back.

As the window for a Uranus launch narrows, here are three key reasons to explore the mysteries of the icy world and its orbiting satellites.

“Do these icy worlds around Uranus also hold that potential?”

3. Subsurface oceans

When the Voyager 2 spacecraft flew by Uranus, it captured images of Uranus’ largest five moons, the only ones known at that time:

- Titania, the largest of Uranus’ moons.

- Oberon, the second-largest moon.

- Umbriel, a dark, pockmarked orb.

- Ariel, another world with canyons and craters marking its surface.

- Miranda, the smallest of the five and one of the most extreme moons in the Solar System.

The moons of Uranus, including: Puck, Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon.

The images showed them all to be heavily cratered, made up of rock and ice, as well as having signs of liquid water erupting from beneath the surface. (The craft also imaged numerous smaller satellite bodies around Uranus.)

From these data, scientists suggest that the moons may have subsurface oceans, similar to the one found on Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

“It just looks bizarre.”

Heidi Hammel, a planetary astronomer who has studied Uranus for decades and served on the Voyager 2 team during its Neptune encounter in 1989, noted some intriguing evidence from the Voyager 2 flyby.

“Most of the icy moons that we’ve done these flybys, we’ve found potential evidence for subsurface oceans, and oceans of water with potential for habitability,” Hammel tells Inverse.

“And so that really begs the question: Do these icy worlds around Uranus also hold that potential?”

Miranda, pictured, is one moon of Uranus that could host a subsurface ocean and even life.

As scientists look for signs of habitability on other worlds, water is considered one of the key ingredients for life. Several moons in the Solar System, such as Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus, have evidence of a subsurface ocean, which means scientists are now investigating them for signs of habitability.

“We’ve learned that the satellites of Jupiter and Saturn, particularly Europa and Enceladus, are what we call ocean worlds and that’s really exciting,” Hofstadter says. “We now think they’re the most likely places where life might exist in our Solar System other than Earth.”

2. Active worlds

Aside from the potential of habitability, the moons of Uranus also show evidence of geological activity. The surface of the moon Miranda is unlike any other object scientists have seen before.

“It just looks bizarre,” Hofstadter says. “People say it looks like you took pieces of different puzzles and stuck them together.”

Miranda shows signs of something unusual: recent geologic activity. One theory suggests that the moon was broken apart by a giant impact and then reassembled back together.

“The outer Solar System can be a good home for life.”

The moon has an odd mixture of older and younger surfaces as a result of a surprisingly high degree of tectonic activity. Revisiting the moons of Uranus would help scientists understand the mysteries behind this recent activity.

“We’d like to understand what drives the activity on these moons because we don’t understand how they could be so geologically active,” Hofstadter says.

1. Unlocking the outer Solar System

Uranus is one of two ice giants in the outer Solar System, the other being Neptune. They derive their name from extreme forms of water deep below their cloud layers.

Unlike Mars or Jupiter, scientists know very little about the two outermost planets in our Solar System. Uranus and its moons are so far away from Earth, approximately 1.9 billion miles, that it’s difficult to obtain any in-depth observations of the icy planet without sending a spacecraft to venture deep outside the Solar System.

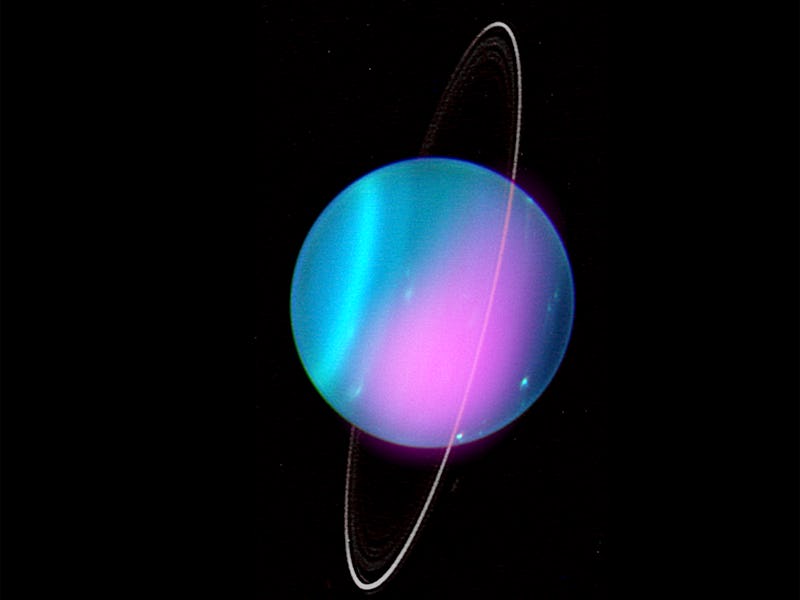

This false-color view of the rings of Uranus was created from a series of images taken by Voyager 2 on Jan. 21, 1986.

“I think one reason they’re so interesting is that we know so little about them,” Hammel says.

The ice giants and their moons make up part of the larger story of the Solar System, and inform scientists’ knowledge of similar exoplanets that they discover orbiting around stars other than the Sun.

“The Voyager spacecraft gave us intriguing hints of what these moons may look like or consist of but it raised more questions than provided answers,” Hammel adds.

As scientists learn more about the icy worlds of the outer Solar System, they realize that searching for signs of habitability or life is not restricted to the planets that are most similar to our own, such as Mars or Venus.

Instead, objects in the outer Solar System can host subsurface oceans beneath their icy surface.

“The outer Solar System can be a good home for life,” Hofstadter says. “So right now we are in a transition time where we’ve learned enough to realize that the terrestrial planets are very important but there’s also great value in exploring these other places.”

This article was originally published on