Human space travel owes everything to one forgotten creature

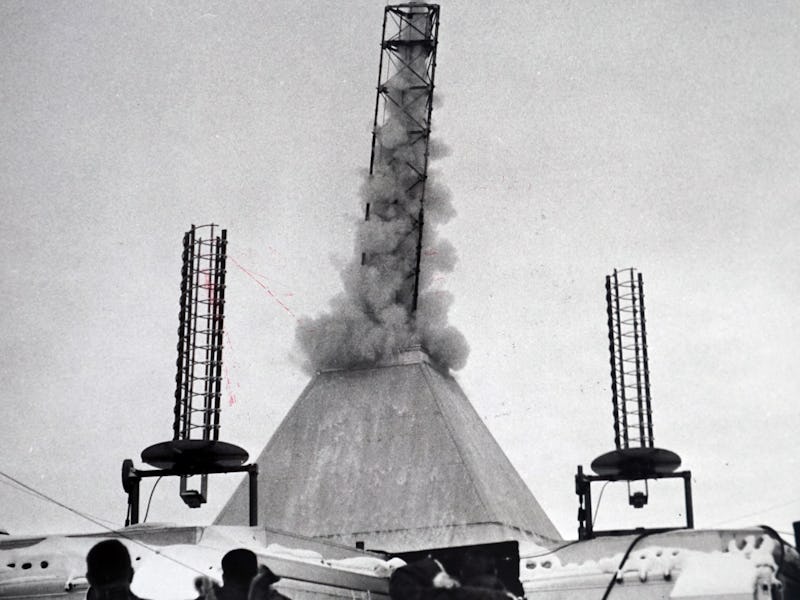

The Aerobee-19 rocket launch proved it was possible to send animals to space and bring them back alive.

Billionaires Richard Branson, Jeff Bezos, and now Jared Isaacman have all traveled to space in 2021. But the three, especially Bezos and Branson, aren’t exactly blazing new territory. After all, Mercury astronaut Alan Shephard made a similar, if somewhat higher, suborbital trip back in 1961. Today, there is a constant human presence in space at the International Space Station.

But even Shephard had his predecessors. On September 20, 1951, almost a decade before Shephard went to space and 70 years before the billionaire crowd made it, a Rhesus monkey named Yorick changed space history.

On that day, Yorick was strapped into the nose cone of United States Air Force’s Aerobee-19 rocket and became the first human-like animal to be successfully launched into space and safely landed... in a way.

“Technically, that monkey survived but died very soon after recovery,” Space historian and National Air and Space Museum Guggenheim fellow Jordan Bimm tells Inverse.

“They weren’t able to reach the rocket in time, and the specimen overheated and died of heat prostration.”

It was a sad and gruesome end for Yorick that, if it went differently, might have made Aerobee-19 a more significant part of the story of early spaceflight. Even at the time, Bimm says, the launch made few waves. But when America turned its attention to the space race with the Soviet Union following the launch of Sputnik in 1957, the Aerobee data would give the newly created NASA the boost they needed to put people into space.

“...a human-like creature could survive a rocket flight.”

Monkeys, Nazi rockets, and Project Blossom — In the wake of WWII, the U.S. Air Force did research with captured Nazi V2 rockets and American-made Aerobee rockets to answer a burning question:

Could a human survive the stresses of a rocket flight and perform meaningful work in space?

To rephrase the question more accurately, Bimm says: “Could a soldier perform a military function during a rocket flight?”

A replica of a German V2 rocket on the island of Usedom in the Baltic sea.

In 1947, the military and the National Institutes of Health partnered to put a collection of fruit flies in the nose cone of a V2 rocket that reached space altitude from its launch site at White Sands, New Mexico. These bugs are the first living things known to have left the planet and made it to space. But the research quickly expanded into a program dubbed Project Blossom, which used creatures considered closer physiological analogs to humans than fruit flies — monkeys being the gold standard.

“Contrast that to the Russian program, which was using dogs,” Bimm says. Their thinking on the Soviet side was that dogs were hardy, and they were survivors. They didn’t want a specimen to die and not survive.”

Survival did indeed turn out to be a bit of a problem for Project Blossom’s space monkeys.

“Sadly, these resulted in just a string of failures leading to the deaths of these monkeys,” Bimm says. “Some of them did reach space altitudes only to die on impact when the parachutes failed.”

Soviet cosmonaut dogs Belka and Strelka flew to space in 1960 aboard Sputnik 5.

When the Nazi rockets ran out, Project Blossom switched to using the less powerful Aerobee rocket, which had a difficult time breaching the Karman line. This internationally recognized edge of space lies at about 62 miles altitude. But Richard Branson, who only flew to 53 miles high, claims he went to space. And so did the scientists sending Yorick up there, too.

Yorick and Aerobee-19 would make it to 44.7 miles altitude.

“If it were Richard Branson, he definitely would say that he was in space,” Bimm says.

“From a medical perspective, if you are above a point in which the problem with keeping you alive is going to be the same in the upper atmosphere as it is in space, it’s essentially space.”

Aerobee-19 was the mission that broke with the past in that the parachute didn’t break. Yorick, and the eleven mice accompanying him on the mission, landed safely in the New Mexican desert. The rodents survived the heat, though Bimm notes they were probably euthanized for further study.

“The public didn’t care.”

“I think the most important thing from this flight was the knowledge that a human-like creature could survive a rocket flight,” Bimm says.

“There was no limit in the actual forces of launch, of zero-G, weightlessness, or the parachute reentry and landing that was going to kill a human.”

Alas, poor Yorick — Aerobee-19 occasioned no jumping and cheering in mission control like when NASA lands a flagship mission today. It just wasn’t seen as a big deal.

“There wasn’t a lot of media coverage. The public didn’t care about it,” Bimm says. “What you do see is a bit of a lull in animal flights. I think there’s like one or two more after this one, but then they drop off for quite a long time.”

When Sputnik launched on October 4, 1957, American interest in spaceflight and sending living creatures up took off. On May 28, 1959, America launched two monkeys named Able and Baker to space aboard a Jupiter rocket. Unlike Yorick, they were recovered alive, and they took the glory.

The NASA space monkey Baker atop a model of a Jupiter rocket in 1959.

“They were able to become the sort of the first celebrity space animals in America,” Bimm says.

Because Able and Baker survived, “they were able to put them on a desk at NASA Headquarters behind the American flag and show them to the public.”

Alas, for poor Yorick, it’s hard to make a big PR push with a dead monkey.

Aerobee’s space medicine legacy— But to say Aerobee-19 was a waste or that Yorick doesn’t deserve a spot in the annals of space heroes.

“It’s not like a watershed triumph or a major landmark flight,” Bimm says, “But it is important because it is sort of the first time that a complex living creature was successfully recovered from an American rocket flight in living condition — at least very, very briefly.”

And the data collected by Aerobee-19 and Project Blossom were essential to the foundations of space medicine as a field. Before Aerobee-19, the idea that anything like a human could survive a rocket flight was purely theoretical, and Yorick showed what to do — and not do — to keep something that looks and acts enough like a human alive through all stages of rocket flight.

“You can’t draw a line directly from that to Project Mercury because the interest does subside for a little bit,” Bimm says.

“But when the emergency of Sputnik happened, they’re not starting from scratch. They can go back to the slides. They can go back to that ten years of preparation by the US Air Force in the Department of Space Medicine.”

This article was originally published on