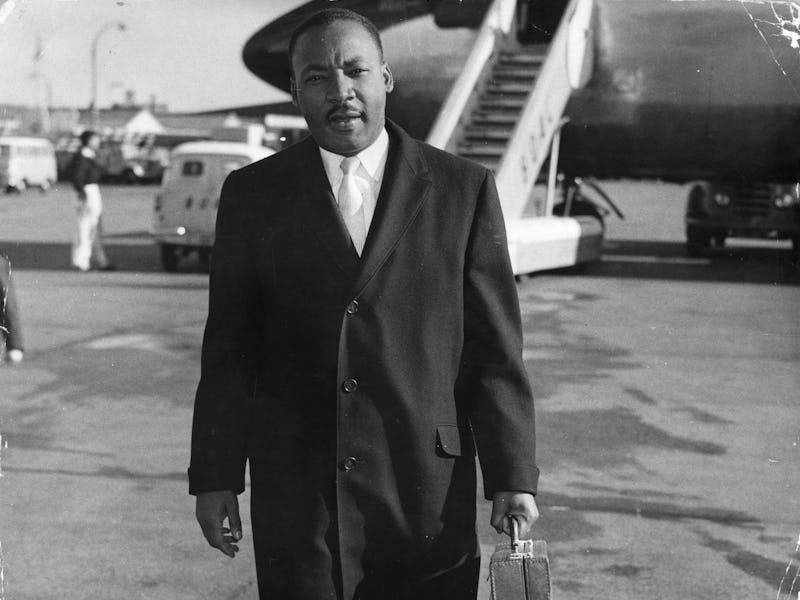

J. Wilds/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

A poverty of the spirit stands in contrast to our scientific abundance.

King's allusions to space travel expose a lasting inequality

Martin Luther King Jr. often reflected on our place in the universe, highlighting the need for equality among humans if we are to venture into the cosmos.

by Passant Rabie"Since I started preaching this sermon, about seven minutes ago, our Earth and you have hurtled through space more than 8,000 miles," Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. told the crowd during one of his 1960s sermons, as quoted in The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. Volume VI: Advocate of the Social Gospel.

As a leader of the civil rights movement in the late 1950s and the early 1960s, MLK often referred to the vastness of the universe, and humankind's advances in space technology as a means to reflect on the need for equality among humans here on Earth.

But as we remember his legacy today — and how he urged others to explore the "heavens" — his speeches also reveal the dire lack of diversity that continues in space science. To understand our place in the cosmos, King suggests, more diverse voices need to be heard.

Martin Luther King Jr. reflected often on the sciences — and particularly space science — in his religious and civil rights speeches.

"There is a sort of poverty of the spirit which stands in glaring contrast to our scientific and technological abundance."

Of the hundreds of people who have donned an astronaut suit, only a handful come from communities of color. According to a factsheet released by NASA in 2018, the space agency had 17 Black astronauts in total at that time.

The situation at NASA reflects a wider issue in space science and astronomy. Around 90 percent of astronomers in the United States are white, and only 1 percent are Black, according to the Nelson Diversity Survey. And just 4 percent of physics and astronomy bachelor’s degrees are earned by African Americans, according to the Statistical Research Center at the American Institute of Physics.

The authors of this study say the reasons why so few Black and African American students pursue — and are awarded — these degrees are "complex and long-standing." But ultimately, they are to do with social justice and how resources are awarded to students.

"The reasons for the paucity of African American students in physics and astronomy are complex and long-standing. But two factors stand out: the lack of a supportive environment in many departments and the enormous financial challenges many of these students face," the authors write.

Yet the study of the universe, King argued, is intrinsic to realizing equality. The vastness of the cosmos dwarfs our human concerns. On the scale of our planet, our host star, and the galaxy which houses our Solar System, among billions of other stars, humans are, perhaps, equally minuscule.

In other words, no one human is considered more superior in the eyes of the universe.

During his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, King reflected on how humankind has made huge leaps forward in science and technology, yet still remains backward when it comes to eradicating poverty and championing equality among humans.

"In spite of these spectacular strides in science and technology, and still unlimited ones to come, something basic is missing," King said during his speech.

"There is a sort of poverty of the spirit which stands in glaring contrast to our scientific and technological abundance."

"We have learned to fly the air like birds and swim the sea like fish, but we have not learned the simple art of living together as brothers," he added.

In the U.S., the civil rights movement under King took hold at the height of a different effort — the Space Race. But many Black Americans felt left out of the advancement towards the Moon and the stars, as is so well documented in the film Hidden Figures.

Katherine Johnson broke barriers as a "computer" for NASA — and as one of the first black women to hold a central role in the effort to put humans into space.

In July 1969, as NASA prepared to send astronauts to the Moon as part of the Apollo program, a group of protestors, led by civil rights leader Ralph Abernathy, one of King's closest aides, gathered outside the Kennedy Space Center just days before the scheduled rocket launch.

The protestors wanted to shift the American public's focus back to the movement, and show there were still things that needed to be fixed in America — despite celebrations of the achievements related to space technology.

As King's followers felt the need to make themselves heard over the space hype, King himself often encouraged others to explore the cosmos, and question humanity's place in the universe.

"Think about the fact, for instance, that the Earth is moving around the Sun so fast that the fastest jet racing it would be left behind sixty-six thousand miles in the first hour of the race," King said during one of his sermons.

"[Notice] the Sun which scientists tell us is the center of the solar system. Our Earth revolves around this cosmic ball of fire once each year, traveling 584,000,000 miles in that year at the rate of 66,700 miles per hour or 1,600,000 miles per day. This means that this time tomorrow we will be 1,600,000 miles from where we are at this hundredth of a second," he said.

"Look at that Sun again. It may look rather near. But it is 93,000,000 miles from the Earth," he added. "In six months from now we will be on the other side of the Sun—93,000,000 miles beyond it—and in a year from now we will have swung completely around it and back to where we are right now."

King's words provided a cosmic context to our existence — and how inequality and social justice should be regarded within that context.

Ultimately, we humans are all the product of the same elements and lifeforms which originally sprouted on this planet, and we are all revolving around the same Sun, on a trajectory alongside billions of other stars that occupy the Milky Way, a galaxy among billions of other galaxies tucked inside an infinite universe that has evolved over 13.8 billion years.

Our time here is small and limited, but as King urges in his speeches, we must all join in the quest to understand the wonder of the cosmos and reflect on our existence within it.

This article was originally published on