“I Almost Spit Out My Coffee”: A New Webb Telescope Early Universe Discovery Has Astronomers Giddy

New galaxy candidates from a James Webb Space Telescope survey have astronomers shocked and thrilled.

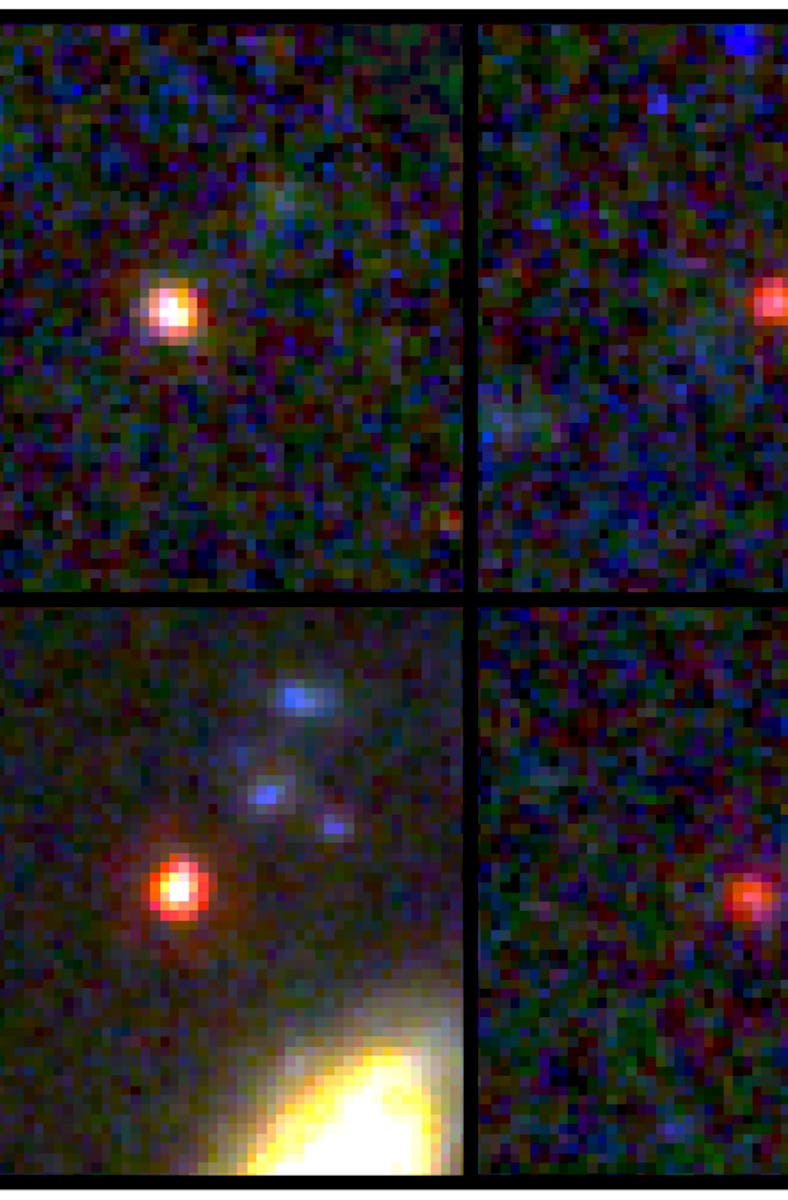

Astronomers found several candidates for hefty galaxies in the early Universe, including one with a possible stellar mass equivalent to 100 billion times that of the Sun. They appeared to the team as bright red “pinpricks” in a patch of sky the size of a marker dot drawn on a thumb held out at arm’s length.

The team behind the new finding was shocked and thrilled. The characteristics of these ancient points, whose light has been journeying through space for most of the history of the Universe, had never been seen before in this way. They hint at a few exciting possibilities. Even just 500 to 800 million years after the Big Bang, these galaxies look put together. The assembly of galaxies and stars may have kickstarted earlier than once thought. The team might also be looking at a supermassive black hole from a long time ago.

The work, described in a paper published Wednesday in Nature, is the latest science to emerge about the deep Universe with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Equipped with four sensitive instruments at frigid temperatures about a million miles from Earth, JWST is able to resolve objects that are faint in the eyes of predecessors like the Hubble Space Telescope.

Images of six candidate massive galaxies, seen 500-800 million years after the Big Bang. The object on the bottom left could contain as many stars as our present-day Milky Way, but is 30 times more compact, according to astronomer Ivo Labbé.

‘Fun and intense’

Ivo Labbé, lead author on the paper and associate professor of astronomy at Swinburne University of Technology in Australia, begins the story of the new research on July 11, 2022, the momentous Monday when President Biden announced the telescope’s debut image. Less than 24 hours later, NASA, the European Space Agency, and the Canadian Space Agency released four more thrilling observations.

Astronomers were “giddy,” Labbé tells Inverse. And the days that followed were “fun and intense,” Rachel Bezanson, associate professor of astronomy at the University of Pittsburgh and co-author on the paper, tells Inverse. Some astronomers were in a race to be the first to publish about the ancient galaxies hiding within the now-public observations. Others were happy to play with the data from their new scientific toy.

Labbé and Bezanson decided to look for something new. They saw an opportunity with the marker-dot-sized patch of sky. It’s the region JWST observed during CEERS, or the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science Survey. CEERS took place a month before the space telescope’s first images went live to validate JWST’s ability to survey galaxies. This was a demo, Labbé says, but it was always designed for everyone to use once the data went public. Labbé, Bezanson, and the team decided to look for bright red points in the survey.

UFOs: Ultra-red Flattened Objects

Labbé says they were jokingly looking for UFOs: ultra-red flattened objects. Team member Erica Nelson found several red disks, Labbé says. “And then she showed one of them, which just looked like a little pin prick. Like a red little dot. And when I looked at it in more detail, I almost spit out my coffee,” Labbé says.

The galaxy candidate objects and their corresponding location in the CEERS field. The CEERS field is roughly the size of a dot from a marker on a thumb extended to arm’s length. The images are a composite of separate exposures from the NIRCam instrument on the James Webb Space Telescope.

“I’ve been looking at these kinds of data for a while now. And I knew immediately what I was looking at. I was looking at what appeared to be a very massive galaxy … and I thought, well, if there’s one, there must be more,” Labbé says. “And so I designed a search that specifically targeted these things and how they look like. And then I found a bunch of them.”

The emission lines from these objects suggest a “shockingly high” number of stars in them, Labbé says. “It was 10 or 100 times higher than you would expect, based on what Hubble had seen.”

Bezanson says that these galaxy candidates seem to be older and more evolved than predicted, perhaps already graduated from the turbulent juvenile chapter in their development. “We think that they’ve gone through a more significant fraction of their lives than we expected, than we would’ve been so bold as to suggest that we would see,” Bezanson says.

What’s next

There are still questions. The mass within these galaxies could be stars. But some of what they see might be heated gas, glowing as it churns around the outer edge of a supermassive black hole. These sorts of bright gravitational pits are called quasars. And if spectroscopy (a technique that analyzes the composition of light) reveals that some of the mass belongs to a quasar, it could open doors for understanding how the gargantuan black holes at the centers of galaxies contributed to their development across the eons.

Labbé and Bezanson will continue looking for more ancient galaxies. Bezanson said they’ll use the natural magnification of a light-bending galaxy cluster, for instance, to see deeper into space.

For now, these ancient galaxy candidates remain an exciting prospect. They have the potential to rewrite the earliest stages of the formation of the biggest galaxies in the Universe.

Author’s note: A previous version of this story said one galaxy candidate had a possible stellar mass equivalent to 1 billion times that of the Sun. It’s actually much more than that: 100 billion times the Sun. The story has been updated to reflect the correct estimate. We regret the error.