NASA discovers a new, two-block-wide crater on Mars with signs of water ice

Two NASA missions revealed two large strikes on Mars are treasure-troves of science.

When a bolide struck the Martian surface on Christmas Eve 2021, it set in motion extraordinary revelations about the Red Planet that NASA made public on Thursday.

It all began when an intriguing alert reached the “frontline,” as geoscientist and InSight science team member Doyeon Kim describes to Inverse, from NASA’s Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport (InSight) lander mission on December 24, 2021.

The signal represented an odd seismic event that had just occurred on Mars. This was the first step into a scientific inquest which eventually involved another NASA mission, the high-flying Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), and triggered an investigation into another marsquake.

Both missions would eventually confirm two large strikes had occurred recently on Mars. Not only did these space rocks excavate large craters, as well as cause strong tremors of the planet’s crust, but they also revealed subsurface ice and unveiled interior details in a manner akin to a Mars “X-ray.”

Details of the Marsquake were published in Nature Astronomy and Science on Thursday.

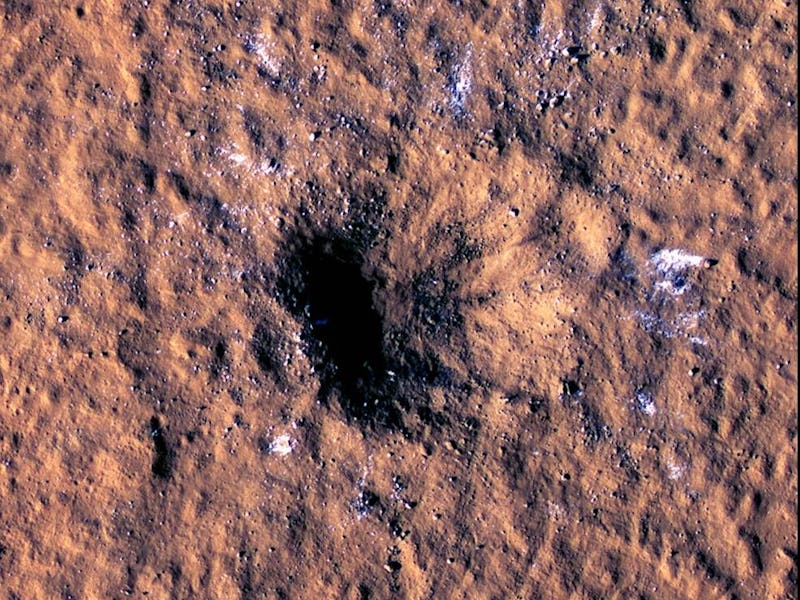

This crater was formed Dec. 24, 2021, by a meteoroid strike in the Amazonis Planitia region. “It’s about two city blocks across,” HiRISE MRO scientist Ingrid Daubar said on Thursday, October 27.

Large, fresh, and rare craters

“These are the two largest fresh impact craters discovered by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter since operations started 16 years ago,” the authors of the Science study write, whose team was led by MRO orbital science operations lead Liliya Posiolova. On top of that, these impacts “created two of the largest seismic events (magnitudes greater than 4.0) recorded by InSight during its 3-year mission.”

Meteoroids strike Mars all the time, Ingrid Daubar, a Brown University planetary scientist, MRO mission scientist, and InSight impact science lead, tells Inverse. And space agencies have detected more than a thousand new craters on the planet over the last couple of decades. But most of them are 10 to 20 feet across.

The Christmas Eve strike was “about two city blocks across,” Daubar said during NASA’s Thursday announcement.

However, both new strikes — which get the numerical value of their names S1094b and S1000a from the number of days that had passed after the start of the mission when they occurred, Kim says — are each more than 20 times larger than most strikes. Large events are “exponentially more rare,” Daubar says, “and it’s part of why it was so exciting.”

These craters are fresh, produced by strikes during the later half of 2021. They are wider than a soccer pitch, both more than 130 meters in diameter.

The researchers found Martian subsurface water ice at the lowest known latitude at which it’s been directly observed.

“The largest of the new craters exposed subsurface water ice,” Daubar says. “That’s really exciting and important because this is the closest to the equator we’ve ever seen water ice exposed.”

This is valuable information for reconstructing the planet’s climate history, and gauging whether or not Mars could have supported life. The finding might also pique the interest of space agencies with their eyes set on sending crewed missions to Mars in the future.

Surface waves on Mars

MRO’s Mars Color Imager was able to time-constrain the formation of the craters to within a 24-hour period, said Posiolova’s study, “making the association with the seismic events highly probable.”

“Before these events,” it goes on to say, “surface waves had not been unambiguously identified on any terrestrial planet other than Earth.”

This is by far the largest jointly-recorded crater impact recorded on Mars, Posiolova said during Thursday’s NASA announcement.

They also produced a way for scientists to advance Mars studies via surface waves. An impact can produce waves that travel across the surface of the planet in both directions, Kim says. He was the lead author of the Science paper, which details InSight’s work with these surface waves.

So scientists can, in the future, learn about the crust as a crater-forming wave travels one distance (say, across the lowlands of Mars’ northern hemisphere) and when another wave wraps around the other side of the planet (across the highlands of Mars’ southern hemisphere).

“We didn’t expect to see anything this big,” Daubar says. “We’re just really, really lucky to have been able to witness this,” since InSight was online during the strike.

This article was originally published on