Discovered: 25,000-year-old structure made from the bones of an Ice Age beast

"Archeology is showing us more about how our ancestors survived."

Six years ago, archeologists discovered a testament to human survival buried beneath birch, pear, and cherry trees. Under layers of dirt, pinpricked with animal burrows and shrubs, was a circle of mammoth bones — evidence of a dwelling built between 25,063 to 24,490 years ago.

Its existence suggests that humans were living nearly 300 miles south of modern-day Moscow during a period of intense cold — and during a time when places of similar latitudes in Europe were already abandoned. The Last Glacial Maximum peaked around 21,5000 years ago and ushered in a rapid decrease in the human population in northern regions.

An analysis of this discovery was published Monday in the journal Antiquity.

This newly unearthed and analyzed structure is the oldest of 70 similar sites found across Ukraine and western Russia. Radiocarbon dating of the site revealed the considerable age of the bones, alongside charred wood and plants. This site is also the first to show evidence of people burning wood for fuel.

“Archeology is showing us more about how our ancestors survived in this desperately cold and hostile environment at the climates of the last ice age,” lead author Alexander Pryor, an archeologist at the University of Exeter, explained. “Most other places at similar latitudes in Europe had been abandoned by this time, but these groups had managed to adapt to find food, shelter, and water.”

Digging in

The mammoth-bone circle itself is quite large — 41 feet in diameter — and the bones form a continuous circle that has no obvious entrance. The walls of the structure are thought to have once stood 30 feet by 30 feet.

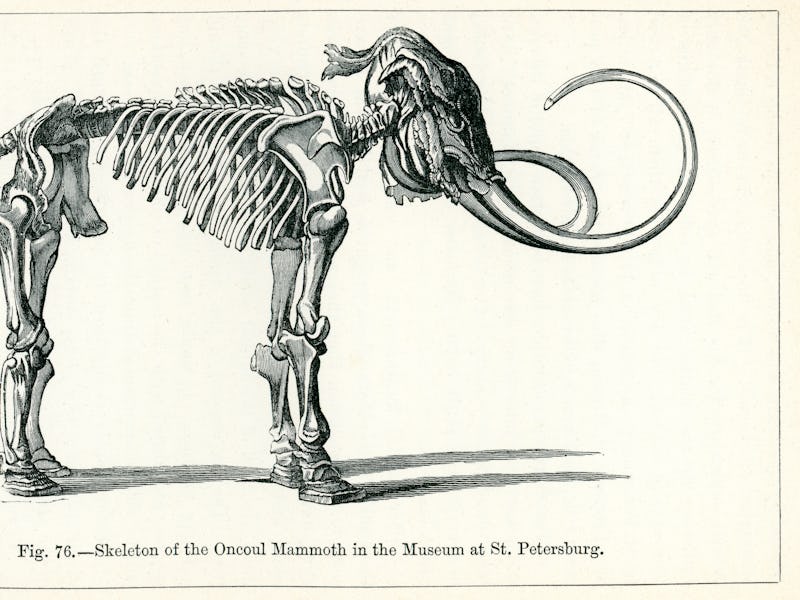

The majority of the bones found at the site are from mammoths: 51 lower jaws and 64 individual mammoth skulls.

The bones themselves are thought to likely be sourced from animal graveyards: 51 lower jaws and 64 individual mammoth skulls. The archeologists also discovered a small number of reindeer, horse, bear, wolf, and fox bones at the site.

The excavation also uncovered more than 300 tiny stone and flint chips — debris leftover from striking stones into sharp tools — and widespread distribution of charcoal and burnt bone, evidence of mixed-fuel fires.

Why was this built?

It’s hypothesized that this structure was a dwelling that offered much-needed shelter during bitter winter seasons, but it’s unclear how long this site was actually inhabited. At the time this site was being built, Europe was frighteningly cold, with winters at temperatures of around negative 4 degrees Fahrenheit.

Bones of other animals were also found, including those of wolves and bears.

Despite this cold, ancient people still put considerable time and energy into building this structure — although the sparse evidence of people living there indicates it was either not occupied for very long, or it was occupied by few.

But there are reasons to believe this site was attractive compared to other European options: For example, the team notes that nearby is a natural spring that seemingly provides unfrozen liquid water throughout the winter — a boon to both mammoths and animals. Analysis of charcoal found at the site also suggests that, when people were living among this structure, there was a grove of conifer trees nearby.

The study authors note that these trees “were perhaps critical to human persistence in this region, while other areas of Northern Europe were abandoned.”

Still, these mysterious bone circles remain enigmatic — evidence of human creativity and creation, but with an unclear purpose. This structure could have been a dwelling, but it could have also been a monument or a ceremonial site. More evidence is needed to say for sure, which means, more digging.

Abstract: Circular features made from mammoth bone are known from across Upper Palaeolithic Eastern Europe, and are widely identified as dwellings. The first systematic flotation program of samples from a recently discovered feature at Kostenki 11 in Russia has yielded assemblages of charcoal, burnt bone, and microlithic debitage. New radiocarbon dates provide the first coherent chronology for the site, revealing it to be one of the oldest such features on the Russian Plain. The authors discuss the implications for understanding the function of circular mammoth-bone features during the onset of the Last Glacial Maximum.