Lunar Orbiter 1: One "ingenious" invention changed space exploration forever

Launched Aug. 10, 1966, Lunar Orbiter 1 was a mission that would set the mold for future planetary science missions.

On August 10, 1966, Lunar Orbiter 1 blasted off from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on a mission to begin a massive photographic survey of the lunar surface. Four days later, it became the first U.S. spacecraft to orbit the Moon.

While Lunar Orbiter 1 was in many ways eclipsed by the later crewed Apollo missions, the orbiter — and the four subsequent Lunar Orbiter missions — were essential to Apollo’s success. And along the way, they took some of the first space images to take the public’s breath away and set the standard by which scientists would conduct robotic planetary science in subsequent decades.

Neck and neck in the space race — The U.S. needed a win in 1966.

While the Ranger 7 through 9 missions had returned live TV images of the Moon before those probes completed their planned impact on the lunar surface in 1964 and ’65, and the Surveyor 1 mission had made the first U.S. soft landing on the Moon in June of 1966, the U.S. had already lost key firsts to the Soviet Union: The USSR had made the first lunar soft landing in February 1966 with its Luna 9 vehicle, while Luna 10 became the first successful orbiter of the moon in April 1966.

The first image of the moon taken by a U.S. spacecraft, Ranger 7, on July 31, 1964.

“The U.S. and the Soviet Union were kind of neck and neck in this,” Matt Shindell, curator of the National Air and Space Museum’s space history department, tells Inverse. “I wouldn’t go so far as to say it was making America look bad, but the Soviet Union definitely had the first success.”

But Lunar Orbiter 1 wasn’t just a step-wise success in the space race — it forged new technological ground and laid the foundation for the U.S. beating the USSR to the Moon with the Apollo missions.

First, there was an entirely different design and scope of mission for the Lunar Orbiter program compared to previous probes, which had only taken photos of specific areas of the Moon. The Lunar Orbiters, beginning with Lunar Orbiter 1, aimed to map the entire Moon, ultimately taking more than 3,000 photographs.

“From those, you had 99 percent coverage of the entire Moon’s surface,” Shindell said. “They used that to study 20 potential Apollo landing sites. In terms of planning Apollo, this mission was incredibly important.”

The flying photo lab — Lunar Orbiter 1 was also innovative in its imaging. While the Ranger vehicles used television cameras to transmit images from the Moon, Lunar Orbiter would use an Eastman Kodak film camera initially developed by the National Reconnaissance Office for the Samos E-1 spy satellite.

But unlike the spy satellites, which Shindell said would drop their exposed film from orbit to be collected with special baskets by aircraft for processing, NASA “developed this really ingenious method of developing the film and then scanning the film inside the spacecraft, sent back via a video signal,” he says. “To me, this is one of the most ingenious, Rube Goldberg-esque imaging systems we’ve ever used.”

A photograph of the moon taken by Lunar Orbiter III in 1967.

Film photography, processing, and transmission was a complicated mechanical dance given the electronics available at the time of Lunar Orbiter 1. The imaging system included two lenses — an 80-millimeter lens for wide-angle photography and a 610-millimeter lens for high-resolution photography — and exposed strips of 70-millimeter Kodak aerial film held in place against a pane of glass by clamps and vacuum.

After exposure, NASA developed the film by pressing it against Kodak Bimat transfer film presoaked in processing solution. Then the original film was dried, cut, and scanned to create an electrical signal that could be sent back to Earth. It was a process that took about two weeks for a full 20-foot spool of film.

Sadly, some of the first images Lunar Orbiter 1 sent back of the lunar surface were a disappointment due to malfunctions with one of the onboard cameras. Shindell notes that the New York Times reported that the images “turned out like an amateur photographer’s over-exposed film.”

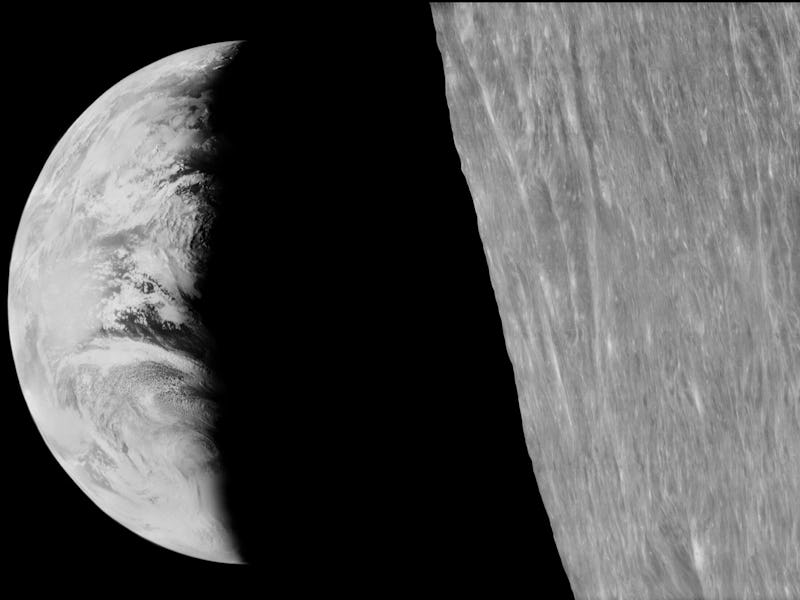

But the spacecraft more than made up for the blurry Moon shots with the first-ever photo of Earth from the Moon, a wide, black and white panoramic image. “This was the first image ever taken that shows this perspective of the Earth seen from the Moon,” Shindell says. “It was printed in newspapers around the world.”

The first image of the Earth as seen from the moon taken by Lunar Orbiter 1 in 1966.

Lunar Orbiter 2 would eventually send back what Shindell calls “awe-inspiring” images of lunar craters, including a photo of the Copernicus crater that the Boston Globe called “the picture of the century.”

“Just like the image of Earth from the Moon that Lunar Orbiter 1 took, this image would later be eclipsed by images from the Apollo images,” Shindell says. “But at the time, it was considered the most incredible image anyone had ever seen from the moon.”

Setting the bar for planetary science— Spoiled as we may be today with high-resolution images of the solar system taken by later planetary science probes such as the Voyager spacecraft, it can be easy to forget the wonder those Lunar Orbiter images inspired.

But science hasn’t forgotten. While more recent missions such as the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter have created datasets that have surpassed the Lunar Orbiter program in terms of resolution, the earlier dataset still has value as it “represents what the Moon looked like at that time,” Shindell says.

In fact, he adds that geologists have been using both the Lunar Orbiter and Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter data to study changes in the Moon’s fault lines over time. “We now have better tools at our disposal to go back into these datasets and look deeper into them.”

But the ultimate legacy of Lunar Orbiter 1 may be how it set the mold and the bar for future planetary missions — including our series of Mars missions, flybys, and orbiters sent to hellish Venus, or the ambitious tours of the outer solar system taken by the Pioneer and Voyager programs.

“The first orbiter around Mars, Mariner 9, was a photo survey of the planet, and what it produced for Mars was very similar to what Lunar Orbiter produced for the Moon,” Shindell says. “You could say the U.S. learned how to do that type of mission from operating the Lunar Orbiter program.”

This article was originally published on