Kate Marvel: “With science plus action, things can get better.”

“We can shape the future that we want.”

As a child, Kate Marvel did not dream of being a scientist; an actress or a writer maybe, but anything apart from science. (She thought it was "so boring.") A single astronomy class at college, however, would change her trajectory forever.

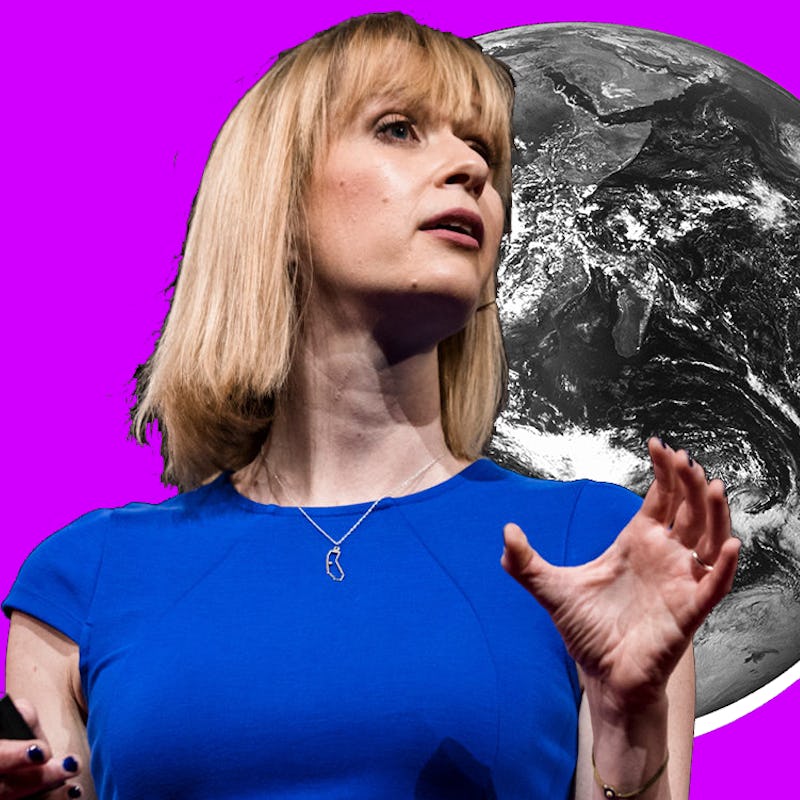

Today, Marvel is a climate scientist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) and Columbia University, where she looks at the big picture of climate change, using supercomputers and satellite observations. She received a Ph.D. in theoretical particle physics from Cambridge University in 2008.

A big chunk of her time is also dedicated to speaking and writing about climate change. On top of a column for Scientific American called “Hot Planet,” and her 2017 TED Talk on clouds and climate change receiving over a million views, she is a contributor to All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis, a new collection of essays by women in the climate movement.

Marvel harbors a reserved optimism about the future of Earth (her favorite planet) and the climate crisis, which she describes as just “a problem with a solution.” She believes we as humans are in control of our destiny, and it’s up to us to work together to prevent the worst.

The following interview, edited for clarity and brevity, is part of Inverse’s Future 50 series, a group of 50 people who will be forces of good in the 2020s.

Your Ph.D. was in theoretical physics, but now you're working as a climate scientist. How did that transition happen?

Fundamentally, I loved physics; I loved using math to find out things about the universe. I was studying everywhere in the universe, and then I realized Earth is the only good part.

It was a much easier transition, intellectually, than I thought. I use math and statistics and physical theories to find out things about the world. It's just now I study this planet, as opposed to all the planets.

“We can shape the future that we want.”

You’ve said before that Earth is your favorite planet. Why is that?

I love space, I've always been interested in space and cosmology. But the thing about space is, it totally wants to kill us. You leave the planet and there's no oxygen, there's no water.

This planet is so special because it's the only place that we know for sure has the absolute perfect conditions for life. And I really like life; I like people, I like societies, I like animals, I like ecosystems, and all of those things happen on this planet.

What were you like as a kid?

I have very great, supportive parents. And I was always encouraged to be interested in things; I was one of those kids who was super into dinosaurs for one month, and then super into marine biology for another.

But from about age 12 on, I was adamant that I didn't want to be a scientist; I didn't want to be someone who did anything with math or science, because I thought it was so boring. And a lot of the reason for that is that the way it was taught to me was really boring. I was like, “Why would anybody care about physics?” I wanted to be a writer; I wanted to be an actress.

And then I got to college and I took an astronomy class for non-majors. I remember sitting in class, thinking, “Oh my god, this is incredible; I could know more about this, and all I have to do is get over my fear of math?”

You're featured in a new collection of essays in All We Can Save. What motivates you to reach out to the general public, and does this ever work against you in academia?

[Writing] helps me as a scientist — to be able to think, “Ok, why is this really important? Why would anybody care about this? How can I explain this thing that I'm thinking about in a way that somebody without this particular background would understand and find relevant?”

I have a ton of criticisms of the traditional structure of academia, where you are a physicist, or you're a biologist, or you can only study this one thing. If you really care about the planet and climate change, you can't just study one thing. Some areas of academia have been better at embracing that than others.

You're pretty active on Twitter.

Twitter can be really useful for broadcasting, and I've met a lot of people in real life that I knew on Twitter first. In general, if somebody seems really awesome on Twitter, they're really awesome in real life.

But sometimes it's more like, if there was a machine that you would enter in a science fact or a silly joke, and then the machine would insult you in many different ways — I feel like that's what Twitter is sometimes.

How are you unwinding these days?

I have a new person in my family, so there’s not a lot of unwinding going on. It's been a stressful time for all of us, and I've found that I get really anxious when I try to read or watch something where anybody is put in any danger for any amount of time — which basically means I can't consume anything with a plot.

I've been watching a lot of The British Baking Show, which I love; just having really strong opinions about people's cakes, and if somebody has a baking disaster and has to go home, it's fine.

Marvel's 2017 TED Talk on clouds and climate change received more than a million views.

You've spoken about clouds being an understudied variable in climate change.

I'm interested in this question of exactly how hot the planet is going to get. And, to a large extent, we don't know how hot it's going to get — because we don't know what humans are going to do; we don't know what carbon dioxide concentrations and greenhouse gas concentrations are going to look like by the end of the century. So, that's the biggest wild card.

But, even if we did know that, we still wouldn't know exactly how hot it was going to get. And that is because of what we call feedback processes. As Earth warms, the climate changes. We get changes in rainfall patterns, in atmospheric humidity, in cloud cover, in ice cover. And all of these things can change the rate of warming.

And clouds are one of the biggest wildcards there. Because clouds are incredibly complicated — they’re hard to get right in a global climate model — and extremely important for the energy balance of the planet; clouds play a really important role in regulating the current temperature of the planet. So, the reason that I have worked on clouds is not that I'm inherently interested in clouds — I actually hate clouds, I just want it to be sunny all the time. But the reason is that they can really affect the planet's response to increased carbon dioxide concentrations.

You come across as somewhat optimistic that humankind can fight the climate crisis.

I wouldn't say it's optimistic, necessarily.

We know why it's getting warmer, and we know where those greenhouse gas emissions are coming from.

And we, as a society, can choose to do something about that — at any time.

I think a lot of people are choosing to do something about that.

I wouldn't say it's optimism so much as it’s just an understanding that this is a problem with a solution.

“With science plus action, things can get better.”

What is your biggest concern about the climate crisis?

As we've seen with the Covid-19 crisis, too, this notion that we have science, and yet, it just isn't enough.

It's not enough to counter people ... who are resistant to hearing those messages.

You can tell people to stay apart from each other and to wear a mask, and some people are going to do it, and then other people, for a whole bunch of different reasons, are going to say, “No way, you're not going to tell me what to do.”

And with climate change, it's the same thing. There's been this notion that, “Oh, well, we're going to respond to climate change by drawing down carbon in the atmosphere and adapting to the new climate, whatever that is, by using the best available science.” And since when have we ever done that?

The thing that keeps me up at night is this kind of irrational human response to rising temperatures. lt's not something that I have any understanding of, because I'm a physicist — I don't study people. But it is the thing that makes me the most frightened.

This series is all about the 2020s. What is one big prediction you have for this decade?

I'm a climate scientist, so I use climate models to say:

"If we do this, this is the realm of possibilities that could arise from those choices.

"So, if we get serious about this; if we decarbonize the electricity sector by 2035, if we change our transportation system, if we come up with viable alternatives to factory-farmed meats, I think we could be looking back on this with pride, saying, 'Hey, we saw this problem coming, and we really took steps to fix it.'"

There will still be climate disruption, the world will still warm — but we really hit off the worst of it.

But, if we don't get serious about this, if we don't prioritize this, then who knows what this next decade is going to bring?

I'm not just talking about climate disruption; I'm talking about the social disruption that also arises in reaction to that. So, things could be really, really bad.

This is not flipping a coin. This is not something that we just have to wait and see how it shakes out — we can shape the future that we want.

Given that we're almost finished with 2020, and it's been such a horrible — sorry, historic — year, what’s one moment that you’ll remember from it?

I mean, I live in New York City. And I don't think I will ever forget the sirens. I don't think I will ever forget walking by the refrigerated trucks parked outside the hospitals. So, I'll remember that; to mark how awful this year was.

But I will also remember how everybody wears a mask in New York. You go out on the street in my neighborhood, everybody's wearing a mask; people have shifted their social lives outdoors. And although cases are rising right now, we're not back where we were in April. And I remember a day in May, where you could hear the birds again. It was fewer sirens — and more birds.

So, that gives me the confidence that, with science plus action, things can get better.

Kate Marvel is a member of the Inverse Future 50, a group of 50 people who will be forces of good in the 2020s.

This article was originally published on