The most epic sci-fi movie on Netflix reveals a dangerous question about our reality

We're already incepted.

In 2010, one science fiction movie managed to change the definition of a word.

You might say this reality-bending caper incepted our collective conscious.

Before Inception, to “incept” was simply to take something in. Now it's understood to mean tricking someone into accepting another person’s idea as their own.

Christopher Nolan’s epic sci-fi thriller explores a literally mind-bending proposition: implanting an idea into someone else’s brain.

“The seed of the idea we plant will grow in this man's mind. It'll change him. It might even come to define him,” Dom Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) tells his client, Saito (Ken Watanabe).

Inserting an idea into someone else’s mind may seem like the stuff of science fiction, but it’s actually rooted more in reality than you might think.

In real life, the way inception works has less to do with the futuristic scientific tech shown in the movie and more to do with methods that already exist. These too can implant ideas into the minds of susceptible masses of people.

In fact, you might be experiencing inception right now.

What is inception — in the movie and IRL?

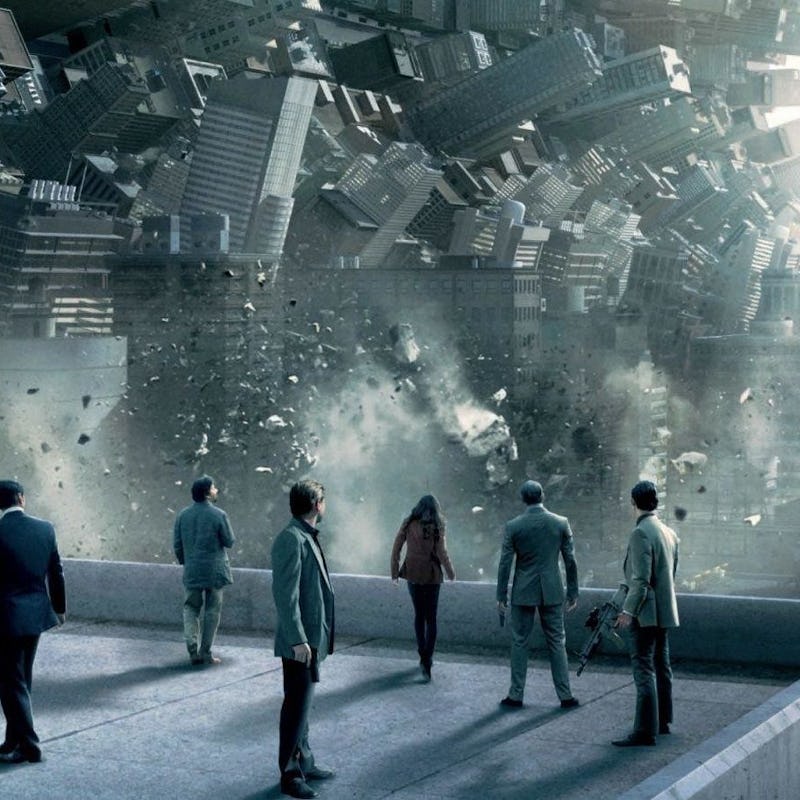

The infamous dream fight scene.

In the movie, Saito hires Cobb to conduct a high-tech form of corporate espionage by breaking into the mind of his business rival, Robert Fischer (Cillian Murphy).

Through a multi-pronged process that involves sedatives and “dream sharing,” Cobbs enters into different levels of Fischer’s dreams, going deeper into the emotional recesses of the man’s mind. He eventually finds the information he needs to implant a specific idea: Fischer needs to give up his father’s business empire for his own good.

By the end of the movie, Cobb has successfully implanted this idea in Fischer’s mind — all while Fischer peacefully sleeps on a plane, blissfully unaware that his mind has been altered. (That is, if you don’t think everything in the movie is a dream.)

As it turns out, inception isn’t just a scientific fantasy conjured up by Nolan. It exists in real life, and one professor has devoted much of her life to studying it.

Elizabeth Loftus is a professor of cognitive psychology at UC Irvine. For decades, Loftus has studied how ordinary people can introduce false memories into other people’s minds using suggestive language or leading questions.

How “dream sharing” works in Inception.

In one study, Loftus and now University of Washington professor Jacqueline Pickrell provided participants with three true scenarios and one made-up scenario about the participant’s childhood, which suggested the participant got lost in a mall when they were five years old. Strikingly, a quarter of participants believed the false memory and began recalling details about this experience that never happened.

Loftus’ research also touches on false memories in courtroom settings, where people may become convinced of a defendant’s guilt based on false information, which has altered their memories. However, other psychologists have criticized the application of Loftus’s methods, suggesting that false memory syndrome has been used as an excuse to discredit child abuse victims who may have repressed memories.

Psychologists and people in positions of influence likely can use the power of suggestion to implant ideas in the mind. But are there ways we can actually infiltrate into the brain using more hardcore science as seen in Inception?

Implanting ideas with machines

During Inception, Cobbs and his team enter into people’s dreaming minds through a mysterious gadget in a silver briefcase. Although the dream infiltrators hook themselves up intravenously to this briefcase, it’s never fully explained how exactly this technology works — just that it was developed by the military. This is what they call dream sharing.

But it’s possible that the intravenous suitcase technology sends some kind of signal or impulse to the brain, functioning as a stylish kind of brain-machine interface.

This robot is designed to be controlled via human brain activity collected by a brain-machine interface.

Brain-machine interfaces, also known as brain-computer interfaces (BCI), facilitate communication between the brain and a machine using electrical signals.

Inception raises an interesting question: Could we use BCIs to implant false memories into a person’s mind by sending electrical signals to the brain?

According to Miguel Nicolelis, the answer is a definitive no. Nicolelis is the head of the Nicolelis Lab at Duke University. He’s been working since the 1990s to show if it’s “possible to link brains to machines.”

According to Nicolelis, in order to interpret signals from people’s dreams — the first step before even thinking about inception — you’d need “to have a library of patterns of their brain.” This means knowing how a brain would react to an infinite number of scenarios.

“That's the reason I believe that we cannot download brains, or we cannot upload content to brains, because they work in a different way than our digital computers do,” Niolelis tells Inverse.

Since the 1960s, researchers have used a technique called neurofeedback, which involves sending signals to the brain to improve people’s well-being as a kind of therapy.

In recent years, researchers have also used neurofeedback to teach subjects to learn a skill or associate a subject — without the subject being aware of it. In a 2016 study published in Current Biology, researchers used fMRI machines to teach subjects to associate the color red with a picture of black and white stripes.

This brain-machine interface was designed by researchers at the Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology. Its purpose is to aid people with severe motor impairments.

Nicolelis refers to this research technique as a form of “subliminal messaging.” But he says that this kind of associative machine teaching is “a far cry from [...] embedding content” — or an idea — “in someone's brain” using BCI.

Teaching someone to associate with an object is very different from implanting an idea using electrical signals, Nicolelis says. The former is possible, but the latter is impossible — at least, from our current understanding of technology and the brain.

He offers an example: Let’s say you tried to infiltrate someone’s mind while they were sleeping, sending a message to their brain about which candidate to vote for in the next election.

“It's not going to happen, because the decision that a person takes to choose a name versus another is much more complex. You cannot send a signal from outside that will change the decision-making process,” Nicolelis says.

“Ideas are mental abstractions generated by a very complex process that we don't understand very well,” Nicolelis says. The idea that we can upload ideas into the brain like a computer, he says, “is very naive.”

The real danger of inception

While mind hackers likely won’t be using stylish briefcases to infiltrate our minds anytime soon, inception is already a real and present danger to us all, Nicolelis argues.

We don’t need to worry about this type of inception — for now.

But it’s happening not through BCI. Instead, he argues, it’s happening through machines most use on a daily basis: computers and smartphones. Actual inception, he says, is happening through social media platforms.

“In social media today, you can create fake news that appeals to primitive prejudices and instincts of the human brain,” Nicolelis says, pointing to the false information that circulates on social media, leading people to unscientific beliefs like the idea vaccines are harmful.

You may not need to hire guards to protect your mind from infiltration a la Inception, but in the era of social media, you’ll need a critical mind to guard yourself against real-life inception happening all around us in the form of propaganda and conspiracy theories.

“I think we're taking science fiction too seriously. Meanwhile, we are forgetting about massive ways to manipulate human minds on a great scale,” Nicolelis says.

Inception is streaming now on Netflix.

This article was originally published on