A monster sunspot just doubled in size — and it’s pointing right at Earth

Should you be worried?

Sunspots are typically no real reason to worry, even if they double in size overnight and grow to twice the size of the Earth itself.

That’s just what happened with Active Region 3038 (AR3038), a sunspot that happens to be facing Earth and could produce some minor solar flares. While there’s no cause for concern, that does mean a potentially exciting event could happen — spectacular auroras.

Although scientists consistently point out that people are in no danger from sunspots like AR3038, that doesn’t stop the popular media from worrying about them, especially ones that seem to grow quickly. But this is all par for the course, according to Rob Steenburgh, the head of the US’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Space Weather Forecast Office.

He points out that this type of rapid growth is exactly what we expect to see at this point in the solar cycle, the 11-year repeating pattern that started again in 2019. He also points out that sunspots of this kind don’t typically produce the types of dangerous solar flares that could knock out satellites or disrupt power grids. It simply lacks complexity.

What is a solar flare?

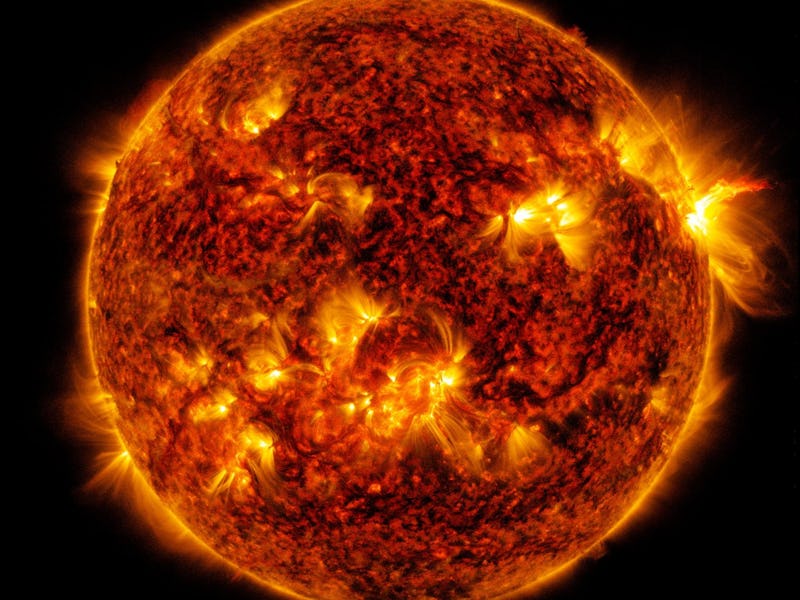

NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory captured this image of a solar flare — as seen in the bright flash in the lower-left portion of the image — on May 3, 2022.

Solar flares occur when the magnetic fields surrounding a sunspot break and rejoin in complex patterns, some of which cause flairs to be ejected out into the solar system. If these hit the Earth, they could potentially cause damage to some infrastructure, especially those reliant on electricity. However, they are much more likely to create spectacular auroras when their ions hit Earth’s own magnetic field.

They are rated in severity, scaling from B (the weakest) to C, M, and X (the strongest). X flares have their own grading system, and the most powerful solar flares, X20, happen less than once per 11-year solar cycle and typically do not face Earth.

The likelihood of an X20 forming due to AR3038 is minuscule, though there was a 10 percent chance of it creating a less powerful X flare. More likely are M flares, which AR3038 has a 25 percent chance of developing before it dies down in size and scale, as sunspots typically do.

Will AR3038 solar flares hit Earth?

It doesn’t look like any of those flares will be directed at Earth, as AR3038 has rotated back out of view and is no longer facing us. There is another active region, AR3040, which had 6 C-class flares in the last 24 hours. So there might still be a chance of some spectacular auroras if the planet happens to be in the path of one of those C-class flares.

If not, the whole episode with the rapid growth of AR3038 will prove another example of the public being generally concerned about what appears to be a threatening turn of events, but which is quite common and even innocuous.

With all the equipment currently set up to monitor the Sun, the general public can rest assured that we’ll have at least some warning before any potentially damaging flare affects our Earth-bound systems. But it might be a while before that happens, so don’t hold your breath.

This article was originally published on Universe Today by Andy Tomaswick. Read the original article here.