This Fossil of a Giant Whale Could Be The Heaviest Known Animal To Date

Scientists still have no idea what it ate.

The blue whale is not only currently the biggest animal on Earth, but scientists long thought that it might be the largest animal to have ever lived. Now fossils unearthed in Peru suggest a giant whale that lived roughly 39 million years ago may have been at least as massive as the blue whale, and potentially roughly twice as heavy, according to a new study published in the August 3 issue of the journal Nature.

The newfound leviathan dubbed Perucetus colossus, whose name literally means "the colossal whale from Peru," was discovered about 13 years ago in an outcrop in the desert on the southern coast of Peru by study co-author Mario Urbina, a paleontologist at the Natural History Museum of the National University of San Marcos in Lima.

"It's one of the driest places on earth," study senior author Eli Amson, a paleontologist, and curator of fossil mammals at the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart in Germany, tells Inverse. "Mario has been fossil-hunting in that desert for several decades. At first, he had to convince the other members of the team that what he found was actually some fossil, because of the sheer size and weird shape of it."

Analysis of small fragments Urbina collected from the outcrop confirmed "this partially visible boulder-looking thing was made of fossilized bone," Amson says. "From that time on, it was clear we were dealing with something incredible. Then they dug. Painstakingly, in hard rock. It literally took a decade to collect the specimen."

The whale had unusually dense, heavy bones

Perucetus was a basilosaurid, an extinct creature that was likely the earliest fully aquatic member of the cetaceans, the group that includes whales and dolphins. Basilosaurids differed in a number of key ways from modern whales — for instance, they still possessed hind limbs, albeit tiny ones. Perucetus' hip bone suggests its hind limbs were only "probably half a meter long," Amson says.

The partial skeleton of Perucetus that researchers unearthed included 13 vertebrae, four ribs, and one hip bone. The scientists estimated Perucetus may have reached up to 20 meters long, based on comparisons of its partial skeleton with complete skeletons of its close relatives.

The colossal whale's skeleton was unusually dense — reaching between 5 to 8 metric tons, it was two to three times heavier than the skeleton of the 25-meter-long blue whale displayed at the Natural History Museum in London, and heavier than that of any known mammal or sea creature. "The vertebrae of this new species are just insane, because of the tremendous amount of additional bone deposited," Amson notes — each weighed well over 100 kilograms.

To estimate the body mass of Perucetus, the researchers depended on the ratios of soft tissue to skeletal mass known from living marine mammals such as manatees and whales. The researchers suggested Perucetus was likely about 180 metric tons in size, but may have ranged from 85 to 340 metric tons. In comparison, the blue whale can weigh more than 150 metric tons, with the largest known weighing 190 metric tons.

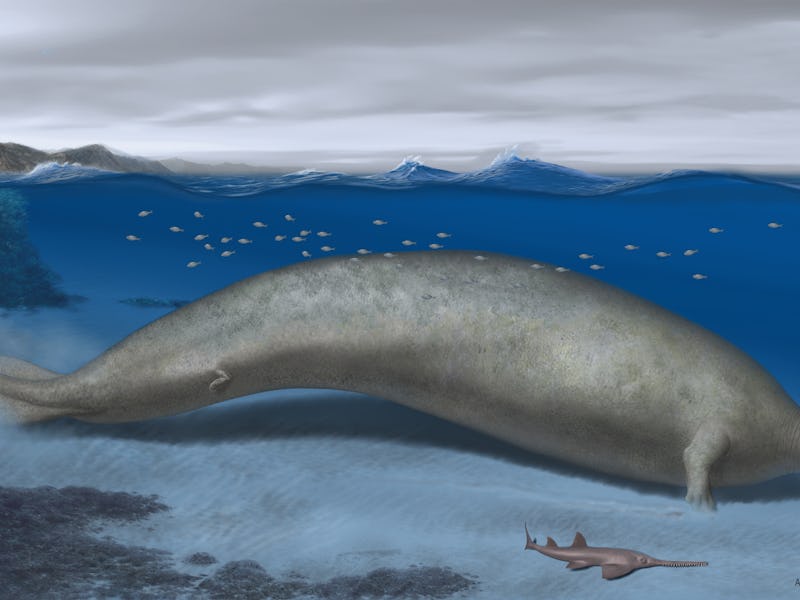

3D model of the fleshed out skeleton of the new species, Perucetus colossus (estimated body length: ~20 meters), along with that of a smaller, close relative (Cynthiacetus peruvianus) and the Wexford blue whale.

"What a big animal! But even more, such unusual, dense, heavy bones, very strange for a big whale," Hans Thewissen, an anatomist and paleontologist at Northeast Ohio Medical University in Rootstown, Ohio, who did not take part in this research, tells Inverse.

Modern giant whales such as the blue whale "are built to move fast and far — they have light skeletons." In contrast, the heavy bones seen in Perucetus are seen in aquatic mammals that mostly live in shallow coastal waters, such as manatees. The extra weight helps them control their buoyancy and orientation. "With such a strong bone mass increase, the swimming style was probably slow, like in manatees," Amson notes.

The overall climate when Perucetus was alive was likely warm and temperate, but the colossal whale likely experienced a cooling event, Amson says. "This could actually explain the tremendous bone mass increase," Amson notes. "If large amounts of blubber were necessary to withstand cooling waters, it had to be compensated for by additional bone to keep a viable buoyancy."

Previously, scientists thought whales only began to reach gigantic sizes about 5 million to 10 million years ago, with the evolution of baleen whales, which filter food from water with plates of baleen. "Thanks to Perucetus, we now know that gigantic body masses have been reached 30 million years before previously assumed," Amson says. "There seems to have no limit to what can be developed through evolution."

"Another whale, or any animal for that matter, equaling or exceeding the size of the largest blue whales is unprecedented," Erich Fitzgerald, a paleontologist at the Museums Victoria Research Institute in Melbourne, who did not participate in this study, tells Inverse. "But I am even more stunned by the discovery of such a whale in the middle Eocene epoch, 30-odd million years before the blue whale and just 10 to 15 million years after whales began their evolutionary voyage in the ocean."

Finding out how large animals have regular bone density and body size "is not just a question of interest to whale researchers," Thewissen says. "If we could figure out which genes are involved, we would understand better how bone is regulated in mammals, and how that can be changed — think of osteoporosis."

Why we still don’t know what the whale might have eaten

Much remains unknown about Perucetus. For instance, the new skeleton lacks a skull, so the researchers cannot say anything certain about what it ate. "The race must now be on to find a skull with a Perucetus skeleton, which could reveal how the jaws worked and whether the teeth––assuming it had teeth––were specialized for an unusual diet," Fitzgerald says.

It seems unlikely that Perucetus lived off small fish, "because Perucetus was most likely not an agile swimmer — you can imagine the inertia of such tremendous body," Amson says. Based off all other known basilosaurids, it likely had a small head, and there is no reason to think that it evolved adaptations to help it filter-feed plankton and other food from the water, as blue whales do.

"Bone mass increase in marine mammals is usually associated with a herbivorous diet, but this would be a complete first for cetaceans, so we deem it unlikely, too," Amson says. Instead, he suggests Perucetus "was a scavenger, feeding on underwater carcasses of some other large animal."

Amson cautions that intact fossils of giant creatures are extremely rare, and their excavation and preparation are time-consuming and expensive. There is a crowdfunding campaign to support the paleontologists in Peru, he adds.

"For me the most important implication of these findings is that we still have a profoundly huge amount of work to do to uncover the evolutionary history of whales," Fitzgerald says. "There are no doubt more, perhaps equally staggering surprises in store from field exploration in the Southern Hemisphere."