65 Years Ago, America Launched Its Most Pivotal Space Mission Ever

Explorer 1 marked the entry of science into what had been a military affair.

With almost 6,000 artificial satellites or objects orbiting the Earth, and tens of thousands more planned to launch in the next few years, it's easy to forget that less than a century ago, the night sky was awash with only stars.

But then the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the first artificial satellite, on October 4, 1957. Not caught off guard so much as disappointed after a launch failure in December 1957, the United States launched its own satellite, Explorer 1, on February 1, 1958. Explorer 1 was seen as a point of national pride, and an important response to the launch of Sputnik by the Soviets. In many ways, it marked the US entry to what would become the space race.

But Explorer 1 was more than just a plot point in a Cold War drama. It returned the first-ever scientific results from outer space, helped convert the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California from a classified missile think tank to a NASA facility that would later put landers and rovers on Mars. It helped catalyze the creation of NASA itself and set the tone for the entire space program to come.

In other words 65 years ago, Explorer 1 helped determine that space exploration would become a civilian and scientific endeavor.

“That set in motion the whole idea of public space science, as opposed to allowing space science to be dominated by the Defense Department,” JPL historian Eric Conway tells Inverse, “Which of course would probably keep most of it classified.”

Today, space exploration in the US is a public affair, with crewed and robotic missions alike exploring the unknown and bringing knowledge back to the scientific community and public at large, rather than sequestering it in classified silos, literal and figurative, within the military-industrial complex. We have Explorer 1 to thank for that.

Explorer 1’s launch

The origins of the space race

When thinking about the earliest days of the space race, it’s important to remember that Sputnik didn’t exactly come out of nowhere.

“The Soviet program was known to the United States, just not very publicly. They had announced it,” Conway says. “People were surprised, I think, that it worked, not that they had done it.”

The US had actually announced its intention to launch an artificial satellite first on July 29, 1955, with the Soviet Union making their own announcement a few days later.

The announcements came as the global scientific community prepared for 1958, the International Geophysical Year. This was meant to be an international collaboration focused on learning more about our planet across a wide array of phenomena — from Earth’s magnetic field to glaciers, from cosmic rays to gravity to seismology and the weather — and based on the International Polar Year collaborations among arctic and antarctic scientists in 1882 and 1932.

The USSR originally planned to build a large satellite replete with scientific instruments, but when the program fell behind schedule, the Soviets launched Sputnik with a simple radio transmitter in order to beat the US into space.

The US, meanwhile, faltered. The December 3, 1957 launch of Vanguard Test Vehicle 3, a satellite developed by the US Naval Research Laboratory, ended in fiery failure as its Vanguard rocket failed to ignite and then exploded.

“JPL was founded to be the US Army's ballistic missile development organization,” Conway says, and its work in the 50s was classified. Rather than designing satellites for orbit, “They were focused on doing suborbital flights because that's what missiles do.”

So while JPL engineers had proposed a satellite for the International Geophysical Year, President Dwight Eisenhower instead went with the Vanguard proposal from the Naval Research Lab, a civilian organization.

“The Eisenhower administration didn't want to expose the missile programs,” Conway says, “so they chose a civilian program with no track record, that hadn't been suffering through all the failures, explosions, et cetera, that were going on in the classified world.”

It was also important to Eisenhower, Conway says, that the US conduct its satellite launch program in the open, in contrast to the Soviets, who though they announced their intent, had kept their Sputnik program behind closed doors.

“He wanted to show that the American system of openness was better,” he says. And so when Vanguard failed, “there were TV cameras watching when it blew up.”

That very public failure led to the Army giving JPL permission to make their own attempt at building a US satellite.

“That,” Conway says, “leads to the 90-day story.”

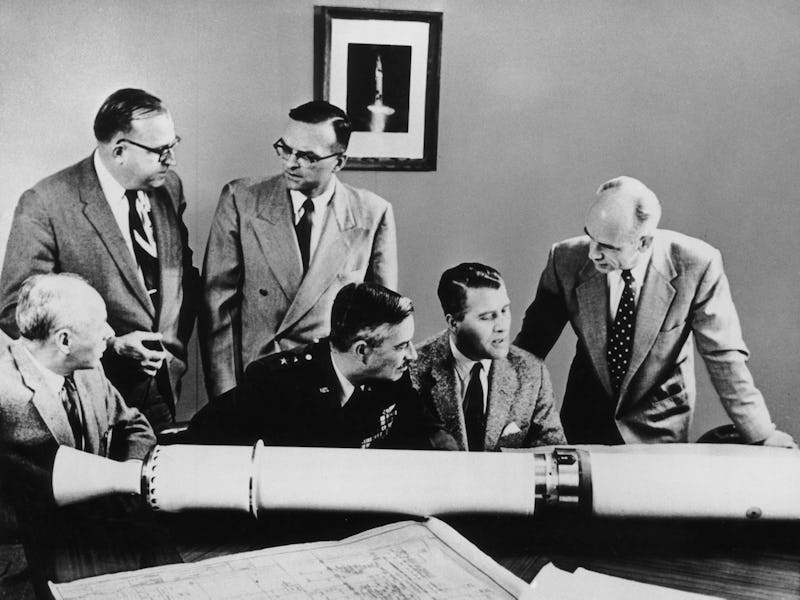

Walter Cronkite demonstrates Explorer 1.

Improvising the first US satellite

When JPL got the call, they were given just 90 days to build a satellite and place it in orbit. So they worked with what they had.

“It was really just kind of an old term called a ‘lashup,’ in which you stick different things that you already have together to make something,” Conway says. “And that's really what Explorer was, it was done to do it quickly.”

The classified missile work JPL conducted involved launching what they called a Reentry Test Vehicle to the edge of space and recovering it, simulating how they might launch a ballistic missile with a warhead that would rain down fire from the sky on an enemy. JPL built twelve Reentry test vehicle craft, three of which flew successfully in 1956 and 1957, according to Conway, so there were nine sitting on Earth when Sputnik launched.

So a Reentry Test Vehicle was modified to carry a cosmic ray detector designed by James Van Allen, then of the University of Iowa, and then placed atop a Juno booster rocket at Cape Canaveral Missile Test Center in Florida, the Juno being derived from an Army ballistic missile design.

”All of the launch technologies of the ‘50s were developed for military purposes and repurposed for civilian use later,” Conway says.

And at 3:47 am GMT on February 1, 1958, Explorer 1 successfully took the US into the space age. The TV cameras made sure to capture that moment too.

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 1981

Explorer 1’s Legacy

The initial consequence of the Explorer 1 mission was that the US officially entered the space race; the US would not sit on the sidelines while the Soviets conquered space.

The scientific results of the mission, however, the first ever returned by a spacecraft, were not immediately understood.

“The Van Allen radiation detector gave very interesting results that they couldn't quite interpret until the second successful flight,” Conway says, which was Explorer 3 on March 26, 1958 — Explorer 2, launched on March 5, failed to reach orbit.

Adding the data from Explorer 3 allowed scientists to recognize that the Earth’s magnetic field captures charged particles from the solar wind emanating from the Sun and concentrates them near the Earth’s poles that now bear James Van Allen’s name. Spacecraft have to be shielded against those charged particles, Conway says, especially if traveling on a polar orbit, circling the globe over the poles instead of over the equator.

But that technical and scientific legacy is dwarfed by the sociopolitical legacy of Explorer 1.

“The biggest legacy is that NASA is created by legislation that's passed that year,” Conway says. “And then JPL and the Huntsville folks, Redstone Arsenal, both join NASA over the next couple of years, so we cease to be Army centers at all.”

JPL and Redstone Arsenal, in Huntsville Alabama, had been focused on creating classified missile technology for the Army. Explorer 1 was the catalyst that led them to become the NASA JPL and Marshall Space Flight Center that we know today.

“So the army loses its space program,” Conway says, “and it becomes a civilian space program.”

It's likely NASA would have been created without Explorer 1, and JPL and Redstone Arsenal might still have joined the nascent space agency, Conway notes, but when, and to what extent their work would be civilian in nature, is hard to tell.

The success of Explorer 1 then set the stage for the space race that followed, and all the decades of open, public, civilian space science that followed. It took JPL and what would become NASA Marshall from designing weapons, to designing dedicated launch vehicles and spacecraft, “ bringing more attention, resources, talent, et cetera, into civilian rocketry,” Conway says. “It kind of opens federal budget floodgates for a while for space science in a way that never really existed before.”