Starlink is Already Causing Hubble Headaches — and the Problem Could Get Worse

A new study found that 3-in-50 Hubble shots have a satellite photobombing them — and that number will only go up as more satellites are launched.

The Hubble Space Telescope keeps getting photobombed, and it’s just going to get worse.

That’s the finding of a new study published Thursday in the journal Nature Astronomy. After examining images in the Hubble archive from 2002 through 2021, a research team led by Sandor Kruk, a postdoctoral researcher with the Max-Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Germany found almost 3 percent of Hubble exposures had a streak of a satellite crossing the field of view, a fraction of images that increased with time.

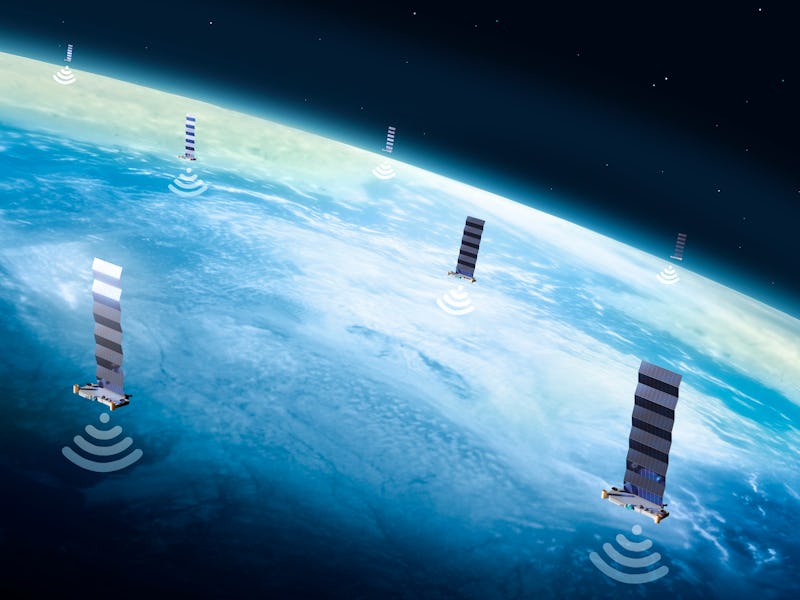

Astronomers have been calling attention to the risk the growing number of satellites in orbit pose to ground-based astronomy for years, but the new paper illustrates that the growing size of satellite mega-constellations, such as the 1,500+ SpaceX Starlink satellites in low-Earth orbit, could obstruct space-based astronomy too. With companies planning to launch as many as 100,000 satellites into orbit by 2030, there’s a real risk of significant interference with astronomy, and of collisions that could damage other satellites and spacecraft, according to Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell.

“We have to start thinking of low Earth orbit as an environment that we're having an environmental impact on and potentially making it harder to use,” McDowell tells Inverse.

The obstructed view of the heavens

Hubble currently orbits the Earth at around 334 miles above the surface, an altitude in lo- Earth orbit that places it below satellites like those of SpaceX, which orbit at about 342 miles altitude.

“It’s orbiting just a few kilometers below the main Starlink shell,” McDowell says. ”So it's looking out through this shell of satellites that are right in front of its nose.”

After examining the Hubble image archive from 2002 through 2021, the researchers found 2.7 percent of exposures exhibited the bright white streak of a satellite passing in front of Hubble while taking the shot.

Moreover, the chances that an individual Hubble exposure would see a satellite increased over time in the archive. Between 2009 and 2020, for instance, the chances Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys instrument would see a satellite in an image was about 3.7 percent. In 2021 images, that increased to 5.9 percent. That corresponds, roughly, to a satellite in 3 out of every 50 pictures.

At the time of the study, there were 1,562 Starlink satellites and 320 One Web satellites in orbit, though both One Web and SpaceX plan to increase the number of these internet broadband-providing satellites. Based on the expected number of low Earth orbit satellites reaching 100,000 by 2030, the researchers calculated that the chances of a satellite crossing Hubble’s field of view at any moment to be between 20 percent and 50 percent, depending on the number of satellites in particular orbits.

“The thing to look at in the Sandor Kruk study is that most of the data come from before the first Starling launch,” McDowell says. “So that the study is sort of the baseline before you add in Starlink.”

A concerted effort

A concept image of Hubble prior to its 1990 launch.

The study began with a citizen science project: 11,000 volunteers from the Hubble Asteroid Hunter project viewed images from the European Hubble Space Telescope archive and flagged instances of asteroid trails.

The researchers then trained two different machine learning algorithms on the images flagged by the volunteers to create models that predicted the number of Hubble exposures seeing a satellite. “The results are consistent between the two methods,” the researchers write.

Astronomers have been concerned about satellite interference in astronomy for a while — one paper drew attention to the possibility in 1986! — but the fact that a growing number of satellites could impact space-based astronomy has been under-examined.

”For the moment, for the most part, it’s not as bad a problem for satellite observatories as it is for ground-based observatories,” McDowell says. “But it is a problem.”

Even if space-based telescopes are not affected as much as ground-based telescopes, Piero Benvenuti, director of the International Astronomical Union’s Centre for the Protection of the Dark and quiet Sky from Satellite Constellation Interference, or CPS, tells Inverse, you have to consider “the much larger cost per image of the space observation.”

Observing time on Hubble is hard for astronomers to come by, McDowell adds. “If your observation gets ‘Starlinked,’ do you do it again, or is it just bad luck for you?” he says. “At the moment, it's just bad luck for you, and you have to reapply for the time from scratch if you want to do your observation again.”

Hubble does have the advantage of being a narrow field-of-view observatory, according to McDowell, meaning it’s focusing on relatively small swaths of the sky at one time, making it easier to avoid satellite crossings. But not some Earth-orbiting observatories, like the big space telescope China plans to launch later this year, don’t have such an advantage.

“This one is going to be cooperating with the Chinese space station that’s only like [217 miles] up or so. And it's a wide field telescope; unlike Hubble, it's trying to do big surveys,” McDowell says, covering wide patches of sky. “I think it is going to be severely affected by satellite streaks.”

Evasive maneuvers

Some satellite operators have already taken actions to try and minimize the impact of their constellations on astronomy, notably SpaceX, which has attempted to darken its Starlink satellites, according to McDowell.

“That doesn't completely solve the problem, but it helps,” he says. “But then there are all of these other companies, and whether they'll adopt the measures that SpaceX is adopting is unclear.”

What’s really needed, McDowell says, are international regulations on how bright satellites can be, and how many satellites can operate in a given orbit. The International Astronomical Union has been working within the UN Committee for Peaceful Use of Outer Space to get discussions going about what a regulatory regime might look like, according to Benvenuti.

It’s also possible it may take some problems, such as satellite collisions costing operators money, or China’s flagship space telescope getting photobombed, to get buy-in for serious discussions on regulations.

“China is planning its own Starlink-like constellation,” McDowell says, “so maybe this will spark more of a discussion within China about regulating space activity and being a bit more careful. So that wouldn't be a bad thing.”