The Webb Telescope Uncovered The Oldest ‘Nearly Dead’ Galaxy Astronomers Have Ever Seen

Is it dead or only resting? Astronomers may never know.

Burnout happens to galaxies, too, and this one hit the wall surprisingly early in the universe.

A team of astronomers recently discovered a galaxy that finished making stars surprisingly early, at a time in the early universe when it should still have been going strong. Kavli Institute for Cosmology astrophysicist Tobias Looser and his colleagues published their work in the journal Nature.

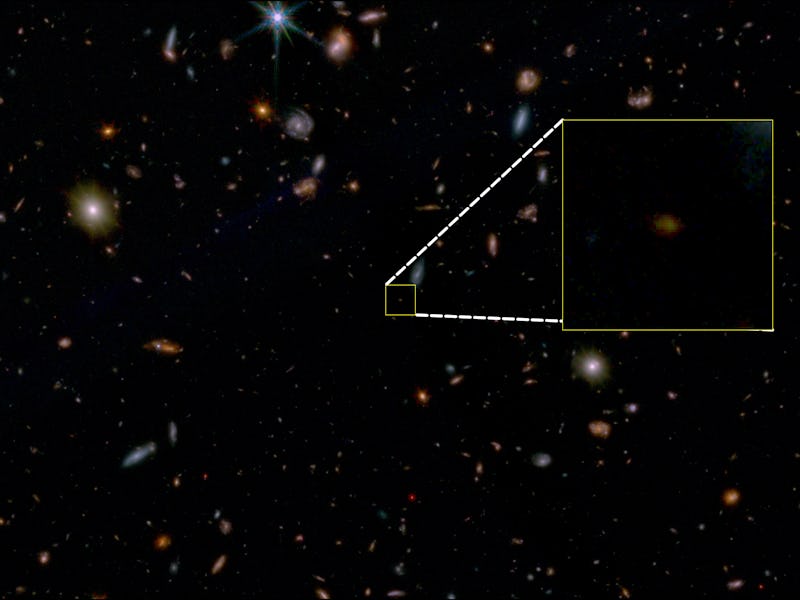

This image shows the universe’s oldest known dead galaxy, JADES-GS-Z7-01-QU.

Looser and his colleagues used the James Webb Space Telescope’s (JWST) instruments to study the spectrum of light from a small galaxy called JADES-GS-Z7-01-QU, which is 13.1 billion light years away, so we’re seeing it as it looked when the universe was just 700 million years old. And the surprising part was what they didn’t see: The galaxy wasn’t emitting any of the wavelengths of light that would suggest new stars being born.

It’s the oldest “dead” galaxy astronomers have ever seen. It dates back to a crucial period in our universe’s history called the epoch of reionization. Light from small galaxies like this one was just beginning to pierce the dense veil of hydrogen gas that shrouded the early universe in darkness.

At this point in time, the little galaxy should still have been churning out new stars from the abundant gas. “It’s only later in the universe that we start to see galaxies stop forming stars, whether that’s due to a black hole or something else,” says study coauthor D’Eugenio, also of the Kavli Institute, in a recent statement.

The galaxy isn’t quite dead yet, at least not in the snapshot of the past we can see from 13.1 billion light years away. From our vantage point, it’s still full of bright young stars with billions of years ahead of them.

“The very young age of the universe unavoidably implies a young stellar population — even if star formation has stopped,” write Looser and his colleagues in their recent paper. But those bright young stars will eventually burn out, and JADES-GS-Z7-01-QU isn’t making new ones to replace them. Once its current generation of stars burns themselves out, the galaxy really will be dead, populated only by the corpses of once-bright stars: black holes, neutron stars, and white dwarfs.

Astronomers have seen this fate befall galaxies in the nearby, relatively modern universe. They’ve even seen it happen to galaxies dating back 12.4 billion years ago. But it’s extremely weird and surprising to see a galaxy run out of material for new stars within the first billion years of existence.

Based on the data from JWST, it looks like the small galaxy spent the first 30 to 90 million years of its life busily making new stars. But about 10 to 20 million years before the moment in time we can see with JWST, the galaxy abruptly stopped making new stars.

Looser and his colleagues could tell that only a single generation of stars was born in the galaxy thanks to the spectrum of light JWST recorded; it revealed that the stars now burning in JADES-GS-Z7-01-QU don’t contain many elements heavier than helium, which are only made inside massive stars. That suggests the stars in this small, dead galaxy don’t contain material recycled from older stars. They’re brand new.

“When we see these fast star formations in other galaxies, they are always also displaying ongoing star formation, suggesting that star formation does not stop as quickly as it did in JADES-GS-z7-01-QU,” D’Eugenio tells Inverse.

So what happened to JADES-GS-Z7-01-QU?

There are a lot of ways for galaxies to burn themselves out. Stars form when dense clumps of gas collapse under their gravity, creating so much heat and pressure in the center that it starts crushing hydrogen atoms together to form helium. So to make new stars, you need a lot of slightly lumpy interstellar gas. Once a galaxy uses up its supply, it stops forming new stars — unless it somehow gets more gas.

If the supermassive black hole lurking at the center of the galaxy is an especially messy eater, it can fling material out of the galaxy at an alarming rate. Supernovae can also shove smaller amounts of gas out of the galaxy; most of it will get caught in the galaxy’s gravity and spiral back in to form new stars, but some will escape into the vastness of intergalactic space.

Galaxies in dense clusters might even find themselves starved out of existence if a neighbor's gravity snatches away cold gas from just outside the galaxy, which might have eventually fallen in to replenish its supply of star stuff. Looser and his colleagues say that's unlikely, given that galaxies in the very early universe had more elbow room than today.

"At that epoch, overdensities were still very loose, and unable to dramatically affect the fate of a galaxy," says D’Eugenio. "A more massive, close neighbor would certainly have an impact, but we can exclude this scenario."

And a galaxy can always use up all its gas; once all the available gas has been pulled into stars or planetary disks, the galaxy’s days as a bustling stellar nursery are over. It’s hard to be sure exactly what happened to this particular galaxy, but the most likely scenarios are a messy supermassive black hole, too many supernovae, or just running out of material. In any of those cases, it would have taken the galaxy less than 100 million years to run out of gas, which matches what the JWST data suggests.

But JADES-GS-Z7-01-QU may get a second chance at life.

Dead — or more scientifically, “quiescent” — galaxies sometimes come back to life if they get a new influx of material. That can happen in a close encounter with another galaxy, or if enough gas from intergalactic space just happens to get caught in the galaxy’s gravity and pulled in. The new material would rejuvenate and reanimate the galaxy, kickstarting a new wave of star formation (until it, too, runs out).

In the nearby universe, astronomers have seen it happen before.

“We know of galaxies that have quenched and then re-ignited, so this scenario is not impossible. So we cannot rule out that this galaxy will re-start forming stars,” says D’Eugenio.

It’s possible that has already happened to JADES-GS-Z7-01-QU sometime in the last 13 billion years, but the light from those newborn stars hasn’t had a chance to reach us yet. We’ll probably never know.