Unexpectedly sharp rocks temporarily derail NASA Curiosity’s Mars mission

Blasted rocks.

Curiosity rover has a confirmed nemesis on Mars: ventifacts. These razor-sharp rock formations, honed to a deadly degree by the Martian wind, almost put paid to Curiosity’s wheels five years ago. And now, NASA reveals these old foes have dramatically stopped the Mars rover in its tracks once more as it searches for clues to Mars’ past and whether it once hosted life.

What’s new — In a post to the Curiosity rover blog on April 7, 2022, NASA reveals that Curiosity has had to abandon its current exploration route up the Greenheugh Pediment, a scientifically interesting area of the aptly named Mount Sharp on Mars that could hold clues to the Red Planet’s wet past.

The setback came after weeks of the rover slowly trundling up the scrubby south face of the Pediment, a steep region of terrain on Mars. According to NASA, on March 18, the rover’s path became intractable. The rover’s cameras revealed to its drivers on Earth the path is littered with ventifacts, also known as ‘gator-back’ rocks — so-called for their resemblance to the hard scales on the back of an alligator.

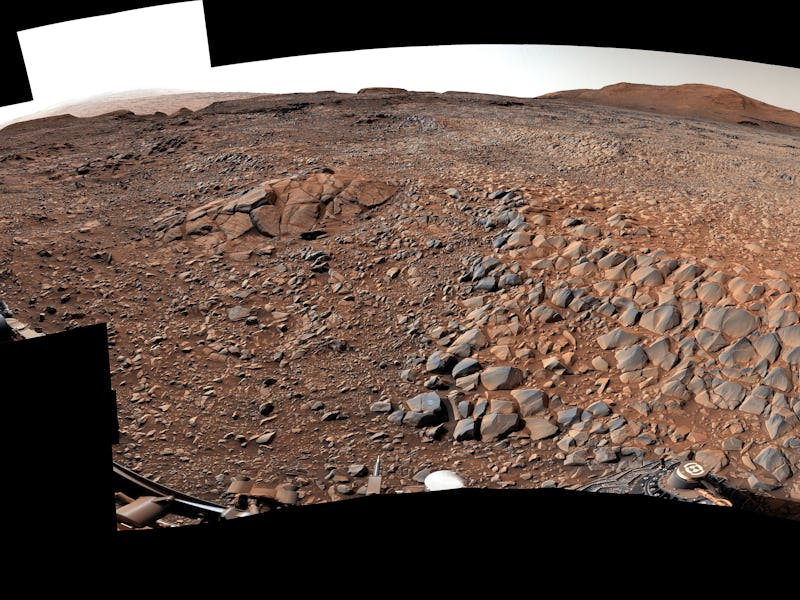

NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover imaged these wind-sharpened rocks, called ventifacts, on March 15, 2022, the 3,415th Martian day of the mission.

“It was obvious from Curiosity’s photos that this would not be good for our wheels,” Curiosity project manager Megan Lin says in a statement on the NASA site. “It would be slow going, and we wouldn’t have been able to implement rover-driving best practices.”

These wind-blown rocks are so sharp they could irreparably damage the rover should it try to struggle onward. Surprisingly, this is the largest number of ventifacts that Curiosity has ever come across on Mars, despite having explored the planet for almost a decade.

Here’s the background — In March 2020, Curiosity briefly made it up to the top of the Pediment — breaking its own record for the steepest hill it had climbed on Mars.

The Greenheugh Pediment summit is covered in red sandstone rubble. It forms part of a larger summit, called Mount Sharp, which is a 3.4-mile high mountain on the Red Planet. Curiosity has been toiling up the hill for the better part of eight years, since 2014.

The area is of interest to NASA because there are signs water once flowed over the terrain. Where there was once surface water flowing on Mars, there may also have been life.

“From a distance, we can see car-sized boulders that were transported down from higher levels of Mount Sharp — maybe by water relatively late in Mars’ wet era,” says Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity’s project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in the same statement.

“We don’t really know what they are, so we wanted to see them up close.”

But ultimately, to discover signs of prior habitability on Mars, the Curiosity rover needs to be able to function — and that means protecting itself from damage.

In March 2017 (what is it about March?), Curiosity came a-cropper when its tire treads were damaged by gator-back rocks. The rover also sustained tire damage in 2013 as a result of crossing over difficult terrain. Today, the team tries to avoid driving Curiosity over any ground that might further damage its tires to try and preserve the mission.

What’s next — Having turned Curiosity back around, the team is now looking to steady Curiosity rover and set it up for success on a new path. On April 7, Curiosity team member and planetary geologist Michelle Minitti posted a diary entry on the mission’s current status:

We successfully drove further down off of the “Greenheugh pediment” as we head toward smoother driving pathways downhill. However, the chaotic jumble of terrain we encountered in the final few rolls of our wheels left a couple of our wheels perched awkwardly... our rover drivers wanted to scoot the rover off of the offending terrain to put all six wheels on terra firma (or the Martian equivalent) before attempting another drive. Thus, our drive today aims to reposition the rover for weekend observations.

Minitti also posted a picture from Curiosity, taken during the descent:

This image was taken by Right Navigation Camera onboard NASA’s Mars rover Curiosity on Sol 3436.

As it continues down this new path, Curiosity will have more opportunities to explore a region of Mount Sharp where the surface material is rich in clay — a signature of past water. This is a region that Curiosity has passed through before, but another chance at observations may reveal new clues to the Red Planet’s past.

“It was really cool to see rocks that preserved a time when lakes were drying up and being replaced by streams and dry sand dunes,” says Abigail Fraeman, Curiosity’s deputy project scientist at JPL, in the April 7 statement.

“I’m really curious to see what we find as we continue to climb on this alternate route.”