Climate prediction study reveals a better way to prepare for natural disasters

New research shows how we can prepare for our future reality.

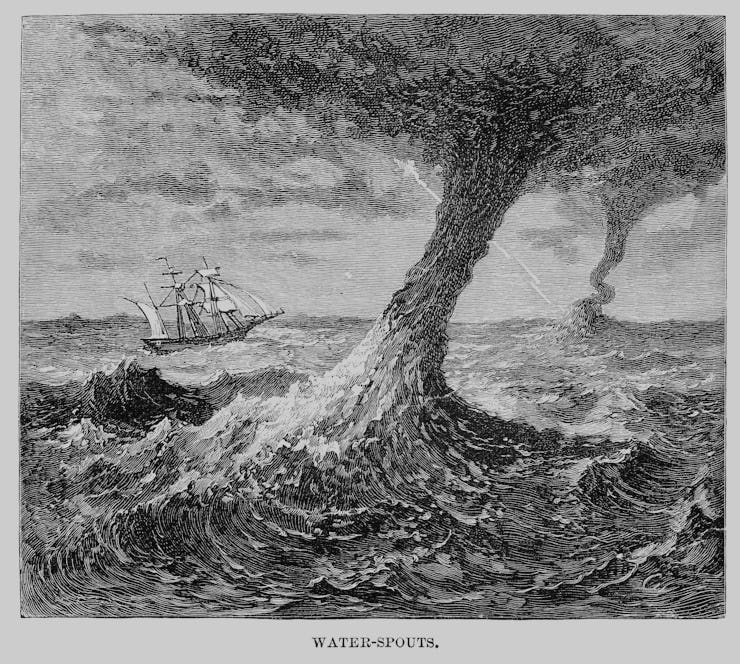

As a result of climate change and a warming planet, natural disasters like hurricanes and floods are an increasing threat to humans throughout the world.

But new research linking climate change to the increase in extreme weather events may help scientists better predict the future of such cataclysmic events — and better protect us from their effects.

Scientists have long known that climate change goes hand-in-hand with increased extreme weather events, but they often stop short of attributing a specific event to global warming. This new study could change that.

Climate change is behind the uptick in events like heat waves, floods, and wildfires, the study shows.

“We know that these are increasing in frequency and intensity. We also know that global warming is happening,” says climate scientist Noah Diffenbaugh, the study’s author, in a video explaining the research.

But finding evidence that global warming is causing specific events has eluded scientists in the past, Diffenbaugh says: “By their very nature, these individual events are difficult to verify.”

In the new study, Diffenbaugh looked at past predictions of weather events, stacking them against what actually happened. Together, the findings not only show that scientists likely underestimated the effects of global warming on extreme weather, but also a path toward better predicting future natural disasters.

How to predict the future

Past research, Diffenbaugh says, has largely looked at the historical record of weather events. Research published in January showed that the last decade was the hottest ever recorded, and that 2019 was the second warmest year since 1880.

The researchers, from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and NASA, also determined humans are driving the trend, as Inverse reported at the time.

But looking only at what’s already happened can skew your perception of what’s likely, especially as climate change continues to accelerate, Diffenbaugh says.

“Climate change has been so steep in so many areas of the world that we now have a false sense of the odds of record-breaking hot events and wet events,” he said. For those record temperatures and precipitation, “our framework is actually too conservative.”

In the new study, Diffenbaugh compared predictions of future extreme weather events modeled on data from 1961 to 2005 with what actually occurred between 2006 and 2017.

The findings reveal that scientists have underestimated the effect of global warming on record-setting hot and wet weather in the Northern Hemisphere — and the same may go for drought prediction, too.

Overall, the study suggests scientists need to consider a wider range of data in their predictive models, including both projections and observations, to better understand how future warming may drive weather patterns.

“What this means is that, going forward, the risks are actually higher than what we would infer just from the historical trends,” Diffenbaugh says.

Tweaking our models is key to preparing for the worse.

“The odds of record-setting events really, really matter,” Diffenbaugh says. “We’ve got to get those numbers right in order to have resilient systems.”

Abstract: Independent verification of anthropogenic influence on specific extreme climate events remains elusive. This study presents a framework for such verification. This framework reveals that previously published results based on a 1961–2005 attribution period frequently underestimate the influence of global warming on the probability of unprecedented extremes during the 2006–2017 period. This underestimation is particularly pronounced for hot and wet events, with greater uncertainty for dry events. The underestimation is reflected in discrepancies between probabilities predicted during the attribution period and frequencies observed during the out-of-sample verification period. These discrepancies are most explained by increases in climate forcing between the attribution and verification periods, suggesting that 21st-century global warming has substantially increased the probability of unprecedented hot and wet events. Hence, the use of temporally lagged periods for attribution—and, more broadly, for extreme event probability quantification—can cause underestimation of historical impacts, and current and future risks.