Why are your allergies so bad? Pollen analysis hints at a manmade cause

People in certain regions may be more vulnerable to allergy spikes.

Long-time allergy sufferers often complain that their seasonal allergies appear to be getting worse every single year.

But this phenomenon isn't psychosomatic. Studies link climate change to recent increases in seasonal allergy and asthma in adults and children.

New research provides further proof of this disturbing link: A study published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences finds climate change-induced temperature warming has lengthened the spring pollen season, exacerbating not only seasonal allergies but other related respiratory issues.

"Climate change isn't something far away and in the future. It's already here in every spring breath we take and increasing human misery," William Anderegg, assistant professor of biology at the University of Utah, explained in a statement.

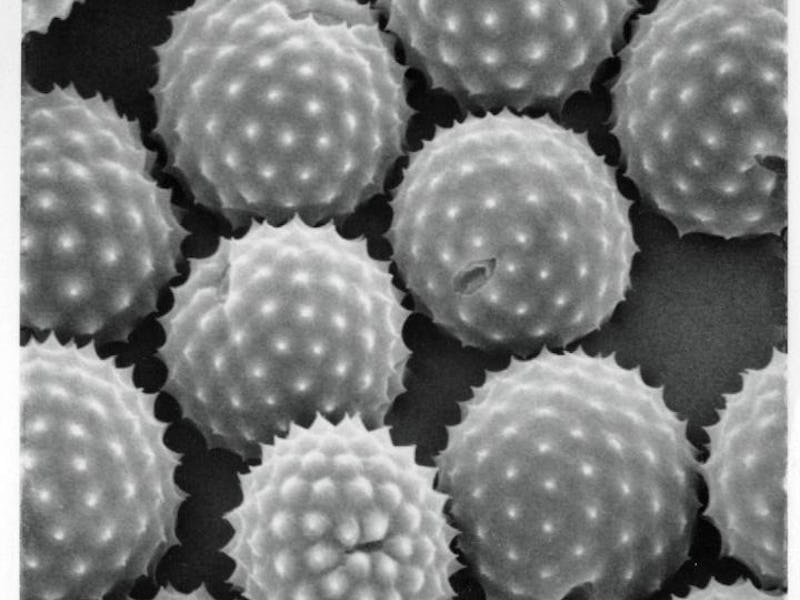

Scanning electron microscopy image of ragweed pollen.

How they did it — Researchers gathered data from pollen stations in 60 North American cities. The data spanned from 1990 to 2018.

They also used statistical models to quantify four key metrics:

- Annual pollen levels

- Spring pollen levels

- Pollen season start date

- Pollen season length

They subsequently tested how eight different climate variables — including temperature, rain, and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere — impacted pollen season.

The scientists used the data and simulation models to answer three simple questions:

- What are the long-term trends in common pollen metrics or pollen season severity?

- Does climate play a significant role in driving variation and trends in pollen metrics?

- How much of the observed trends in pollen metrics can be attributed to recent human-induced climate change?

Does climate change cause allergies?

Overall, the researchers found robust data linking changes in pollen season severity to climate change.

Since 1990, pollen season lengthened by at least 8 days and pollen levels rose by 21 percent, suggests the analysis. Pollen seasons also began 20 days earlier on average.

The researchers concluded that human-induced — also known as anthropogenic — climate change — contributed modestly (roughly 8 percent) to changes in pollen levels and significantly (roughly 50 percent) to the earlier start date and longer length of pollen season.

Of the different climate variables studied, rising temperature levels, on average, played the most significant role in affecting pollen metrics.

"The strong link between warmer weather and pollen seasons provides a crystal-clear example of how climate change is already affecting peoples' health across the U.S.," Anderegg said.

The study team speculates temperature levels affect a plant's seasonal processes — also known as phenology — which influences when and how plants release pollen loads.

A figure from the study showing a worsening pollen season in North America.

Researchers found the most significant seasonal changes over time in the midwestern U.S. and Texas, suggesting that people in certain regions may be more vulnerable to climate change-related allergy spikes.

Ultimately, the team found human-induced climate change contributed more to pollen changes between 2003-2018, suggesting rises in global warming seen in the past two decades have especially worsened pollen season.

Digging into the details — Unlike previous studies, which focused more on small-scale research linking climate change to pollen levels, this study focuses on a much bigger field of study: the continent of North America.

"A number of smaller-scale studies — usually in greenhouse settings on small plants — had indicated strong links between temperature and pollen," Anderegg said.

"This study reveals that connection at continental scales and explicitly links pollen trends to human-caused climate change."

However, the study has its limitations: The researchers think they may have even underestimated the impact of climate change on pollen levels. The paper, in turn, doesn't consider other factors that could be affecting pollen metrics, like land-use shifts, and changes in urban vegetation and species.

A woman with seasonal allergies due to pollen. The study discusses how pollen could exacerbate seasonal allergies.

Why it matters — A longer pollen season means greater human exposure to pollen — the cause of most seasonal allergies.

The study also briefly highlights the links between pollen and allergies, explaining "pollen is an important trigger for many allergy and asthma sufferers."

Pollen count is also associated with viral respiratory infections, say the researchers. It's an alarming consideration, given Covid-19 severely affects the lungs. Preliminary research, in turn, suggests Covid-19 may pose a greater threat to people with asthma. Many people also confuse allergy symptoms with Covid-19 symptoms, which could inadvertently lead to the spread of the diseases.

What's next — The world's leaders are furiously working to tamp down on greenhouse gases and restrict global warming per the Paris Agreement. Their efforts may curb intensifying seasonal allergies — though it very much remains to be seen.

For now, the best thing we can do to avoid triggering seasonal allergies and asthma is to minimize pollen exposure. Doctors advise seasonal allergy sufferers to avoid outdoor activities in the early morning — the time when pollen counts peak.

For the sake of your health, consider closing the bedroom window at night and switching your morning jog to an evening one.

Abstract: Airborne pollen has major respiratory health impacts and anthropogenic climate change may increase pollen concentrations and extend pollen seasons. While greenhouse and field studies indicate that pollen concentrations are correlated with temperature, a formal detection and attribution of the role of anthropogenic climate change in continental pollen seasons is urgently needed. Here, we use long-term pollen data from 60 North American stations from 1990 to 2018, spanning 821 site-years of data, and Earth system model simulations to quantify the role of human-caused climate change in continental patterns in pollen concentrations. We find widespread advances and lengthening of pollen seasons(+20 d) and increases in pollen concentrations (+21%) across NorthAmerica, which are strongly coupled to observed warming. Humanforcing of the climate system contributed∼50% (interquartile range: 19–84%) of the trend in pollen seasons and∼8% (4–14%)of the trend in pollen concentrations. Our results reveal that anthropogenic climate change has already exacerbated pollen seasons in the past three decades with attendant deleterious effects on respiratory health.

This article was originally published on