A Weird Final Test for Boeing’s Starliner Uncovered the Likely Cause of Several Recently-Failed Thrusters

Sometimes you got to push against a million-pound structure in space.

On Saturday, the Boeing Starliner pushed ever so slightly against the International Space Station (ISS) as part of a test to evaluate several recently-failed thrusters.

During the final phase of the Starliner’s docking rendezvous two weeks ago, as the vehicle was in the final stretch to deliver the project’s first-ever passengers to the ISS for Boeing’s Crew Flight Test mission, five thrusters on the Starliner failed. One thruster called B1A3 showed a strange signature. That day, it showed only 11 percent thrust during one firing, and nothing on a second firing. The team decided to deselect it. It will not be used for the remainder of Starliner’s flight. But the other four were still in need of evaluation on Saturday June 15, during a hot fire test.

Starliner is a week away from attempting to undock from the ISS, when it will navigate into prime position in low-Earth orbit, then careen through the atmosphere to touchdown on land in White Sands Space Harbor in New Mexico before sunrise on June 26.

The Starliner flew two astronauts, Butch Wilmore (left) and Suni Williams (right) to space on June 5. The duo will return to Earth onboard the same vehicle.

Saturday’s hot fire test began with a short pulse of all the thrusters. This includes the three good ones, and the four that had failed before docking. This short pulse lasted a quarter of a second. They produced an acceptable amount of force at around 300 pounds per square inch.

Teams also examined the thrusters’ chamber pressures. Steve Stich, manager of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, told reporters on Tuesday that this is a bit like measuring the health of your tires by checking their air pressure. The readings also looked normal.

There was another dimension to the testing. They “took advantage” of the ISS guidance navigation control system to look at the thruster firings, Stich said.

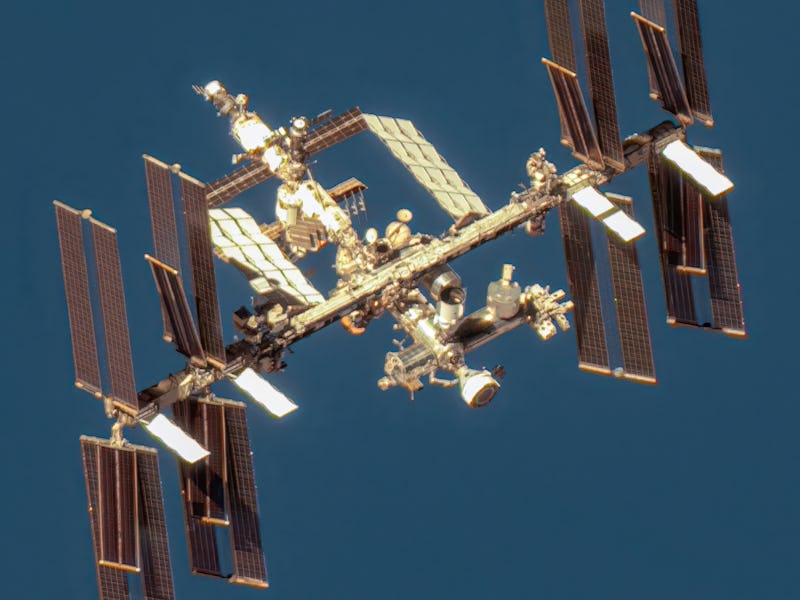

The Starliner spacecraft is pictured docked to the forward port on the space station’s Harmony module. The ISS was 263 miles above the Mediterranean Sea when this picture was taken.

“The way we do that is we fire the thrusters each for about 1.2 seconds, and then we look at the response in the ISS flight control system to measure the acceleration from the thruster,” he said. The ISS weighs a million pounds. But by using this method, the team could see how the thrusters performed, by detecting by how much they were trying to move the station.

Teams did this test for all seven thrusters, which all showed nominal readings. That includes the thrusters that failed during docking.

The testing leads the teams to believe that the thrusters are prone to overheating during docking. Higher temperatures may have caused propellant to vaporize, interrupting the mixing of oxidizer and fuel required for the thrusters to properly work, which then reduced the thruster pressure and resulted in the lower readings.

The thrusters will burn up in Earth’s atmosphere. They belong to the Starliner’s service module, which the Starliner will jettison before the crew module begins landing procedures. With no hardware to examine back on Earth, these tests are the last glimpse teams will get of the thrusters of the U.S.’s new human-rated spacecraft.